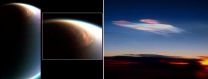

(Press-News.org) NASA scientists have identified an unexpected high-altitude methane ice cloud on Saturn's moon Titan that is similar to exotic clouds found far above Earth's poles.

This lofty cloud, imaged by NASA's Cassini spacecraft, was part of the winter cap of condensation over Titan's north pole. Now, eight years after spotting this mysterious bit of atmospheric fluff, researchers have determined that it contains methane ice, which produces a much denser cloud than the ethane ice previously identified there.

"The idea that methane clouds could form this high on Titan is completely new," said Carrie Anderson, a Cassini participating scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and lead author of the study. "Nobody considered that possible before."

Methane clouds were already known to exist in Titan's troposphere, the lowest layer of the atmosphere. Like rain and snow clouds on Earth, those clouds form through a cycle of evaporation and condensation, with vapor rising from the surface, encountering cooler and cooler temperatures and falling back down as precipitation. On Titan, however, the vapor at work is methane instead of water.

The newly identified cloud instead developed in the stratosphere, the layer above the troposphere. Earth has its own polar stratospheric clouds, which typically form above the North Pole and South Pole between 49,000 and 82,000 feet (15 to 25 kilometers) -- well above cruising altitude for airplanes. These rare clouds don't form until the temperature drops to minus 108 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 78 degrees Celsius).

Other stratospheric clouds had been identified on Titan already, including a very thin, diffuse cloud of ethane, a chemical formed after methane breaks down. Delicate clouds made from cyanoacetylene and hydrogen cyanide, which form from reactions of methane byproducts with nitrogen molecules, also have been found there.

But methane clouds were thought unlikely in Titan's stratosphere. Because the troposphere traps most of the moisture, stratospheric clouds require extreme cold. Even the stratosphere temperature of minus 333 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 203 degrees Celsius), observed by Cassini just south of the equator, was not frigid enough to allow the scant methane in this region of the atmosphere to condense into ice.

What Anderson and her Goddard co-author, Robert Samuelson, noted is that temperatures in Titan's lower stratosphere are not the same at all latitudes. Data from Cassini's Composite Infrared Spectrometer and the spacecraft's radio science instrument showed that the high-altitude temperature near the north pole was much colder than that just south of the equator.

It turns out that this temperature difference -- as much as 11 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 12 degrees Celsius) -- is more than enough to yield methane ice.

Other factors support the methane identification. Initial observations of the cloud system were consistent with small particles composed of ethane ice. Later observations revealed some regions to be clumpier and denser, suggesting that more than one ice could be present. The team confirmed that the larger particles are the right size for methane ice and that the expected amount of methane -- one-and-a-half percent, which is enough to form ice particles -- is present in the lower polar stratosphere.

The mechanism for forming these high-altitude clouds appears to be different from what happens in the troposphere. Titan has a global circulation pattern in which warm air in the summer hemisphere wells up from the surface and enters the stratosphere, slowly making its way to the winter pole. There, the air mass sinks back down, cooling as it descends, which allows the stratospheric methane clouds to form.

"Cassini has been steadily gathering evidence of this global circulation pattern, and the identification of this new methane cloud is another strong indicator that the process works the way we think it does," said Michael Flasar, Goddard scientist and principal investigator for Cassini's Composite Infrared Spectrometer (CIRS).

Like Earth's stratospheric clouds, this methane cloud was located near the winter pole, above 65 degrees north latitude. Anderson and Samuelson estimate that this type of cloud system -- which they call subsidence-induced methane clouds, or SIMCs for short -- could develop between 98,000 to 164,000 feet (30 to 50 kilometers) in altitude above Titan's surface.

"Titan continues to amaze with natural processes similar to those on the Earth, yet involving materials different from our familiar water," said Scott Edgington, Cassini deputy project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. "As we approach southern winter solstice on Titan, we will further explore how these cloud formation processes might vary with season."

The results of this study are available online in the journal Icarus.

INFORMATION:

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. JPL, a division of the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The CIRS team is based at Goddard. The radio science team is based at JPL.

More information about Cassini is available at the following sites:

http://www.nasa.gov/cassini

http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov

In a study just published in the International Journal of Cardiology, researchers from the K.G. Jebsen Center for Exercise in Medicine – Cardiac Exercise Research Group (CERG) at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) and the Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery at the St. Olavs Hospital in Trondheim, Norway have shown that shutting off the blood supply to an arm or leg before cardiac surgery protects the heart during the operation.

The research group wanted to see how the muscle of the left chamber of the heart was affected by a technique, called ...

Endurance athletes taking part in triathlons are at risk of the potentially life-threatening condition of swimming-induced pulmonary oedema. Cardiologists from Musgrove Park Hospital, Taunton, writing in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, say the condition, which causes an excess collection of watery fluid in the lungs, is likely to become more common with the increase in participation in endurance sports. Increasing numbers of cases are being reported in community triathletes and army trainees. Episodes are more likely to occur in highly fit individuals undertaking ...

Six Case Western Reserve scientists are part of an international team that has discovered two compounds that show promise in decreasing inflammation associated with diseases such as ulcerative colitis, arthritis and multiple sclerosis. The compounds, dubbed OD36 and OD38, specifically appear to curtail inflammation-triggering signals from RIPK2 (serine/threonine/tyrosine kinase 2). RIPK2 is an enzyme that activates high-energy molecules to prompt the immune system to respond with inflammation. The findings of this research appear in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

"This ...

Newly published findings from the University of Waterloo are giving women with bad backs renewed hope for better sex lives. The findings—part of the first-ever study to document how the spine moves during sex—outline which sex positions are best for women suffering from different types of low-back pain. The new recommendations follow on the heels of comparable guidelines for men released last month.

Published in European Spine Journal, the female findings debunk the popular belief that spooning—where couples lie on their sides curled in the same direction—is ...

Down syndrome is the most common chromosomal abnormality in humans, involving a third copy of all or part of chromosome 21. In addition to intellectual disability, individuals with Down syndrome have a high risk of congenital heart defects. However, not all people with Down syndrome have them – about half have structurally normal hearts.

Geneticists have been learning about the causes of congenital heart defects by studying people with Down syndrome. The high risk for congenital heart defects in this group provides a tool to identify changes in genes, both on and ...

In early drug discovery, you need a starting point, says Northeastern University associate professor of chemistry and chemical biology Michael Pollastri.

In a new research paper published Thursday in the journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, Pollastri and his colleagues present hundreds of such starting points for potentially treating African sleeping sickness, a deadly disease that claims thousands of lives annually.

Pollastri, who runs Northeastern's Laboratory for Neglected Disease Drug Discovery, ...

WASHINGTON – October 24, 2014 – Policy options for climate change risk management are straightforward and have well understood strengths and weaknesses, according to a new study by the American Meteorological Society (AMS) Policy Program.

"Large gaps remain in society's consideration of climate policy," said Paul Higgins, the author of the study. "This study can help in the development of a comprehensive strategy for climate change risk management because it explores a much larger set of policy options."

The study identifies four categories of climate ...

Washington, D.C., October 24, 2014 -- Only 6 percent of U.S. hospitals are well-prepared to receive a patient with the Ebola virus, according to a survey of infection prevention experts at U.S. hospitals conducted October 10-15 by the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC).

The survey asked APIC's infection preventionist members, "How prepared is your facility to receive a patient with the Ebola virus?" Of the 1,039 U.S.-based respondents working in acute care hospitals, about 6 percent reported their facility was well-prepared, while ...

LAWRENCE – 'Call your mother' may be the familiar refrain, but research from the University of Kansas shows that being able to text, email and Facebook dad may be just as important for young adults.

Jennifer Schon, a doctoral student in communication studies, found that adult children's relationship satisfaction with their parents is modestly influenced by the number of communication tools, such as cell phones, email, social networking sites, they use to communicate.

Schon had 367 adults between the ages of 18 and 29 fill out a survey on what methods of communications ...

VIDEO:

The Jones lab details a new target to fighting HIV.

Click here for more information.

LA JOLLA—Like a slumbering dragon, HIV can lay dormant in a person's cells for years, evading medical treatments only to wake up and strike at a later time, quickly replicating itself and destroying the immune system.

Scientists at the Salk Institute have uncovered a new protein that participates in active HIV replication, as detailed in the latest issue of Genes & Development. ...