(Press-News.org) This news release is available in German.

While neurons rapidly propagate information in their interior via electrical signals, they communicate with each other at special contact points known as the synapses. Chemical messenger substances, the neurotransmitters, are stored in vesicles at the synapses. When a synapse becomes active, some of these vesicles fuse with the cell membrane and release their contents. To ensure that valuable time is not lost, synapses always have some readily releasable vesicles on standby. With the help of high-resolution, three-dimensional electron microscopy, scientists at the Max Planck Institute of Experimental Medicine in Göttingen succeeded in demonstrating that these fusionable vesicles have a very special characteristic: they already have close contact with the cell membrane long before the actual fusion occurs. In addition, the research team also decoded the molecular machinery that facilitates the operation of this docking mechanism.

The fusion of the neurotransmitter vesicles with the cell membrane involves close cooperation between numerous protein components, which monitor each other and ensure that every single 'participant' is always in the right place. This is referred to as the fusion machinery and the comparison is an apt one: if a cogwheel in a clock mechanism is broken, the hands do not move. In a similar way, faulty or missing molecules impair synaptic operations.

In research studies carried out some years ago, Nils Brose and his colleague JeongSeop Rhee from the Max Planck Institute of Experimental Medicine in Göttingen already demonstrated that the transmission of information at the synapses in genetically modified mice, in which all known genes of the Munc13 or CAPS proteins had been switched off, is severely defective. Although the neurons of the genetically modified mice do not differ from those of healthy mice when examined under an optical microscope, if Munc13 is missing, the release of neurotransmitters actually grinds to a halt completely. Brose and Rhee's findings showed that to be able to react immediately to signals at all times, each synapse must keep a small number of 'readily releasable' fusionable vesicles on standby.

But how do Munc13 and CAPS convert the vesicles to this kind of fusionable state? To answer this question, the Göttingen-based scientists studied the synaptic contacts in the minutest possible detail. To do this, neurobiologists Cordelia Imig and Ben Cooper, who have been working with Brose and Rhee for many years, used a high-pressure freezing process. This involves the rapid freezing of neurons in the brain tissue under high pressure so that no disruptive ice crystals are formed and the fine structure of the cells is particularly well conserved. The samples obtained in this way were then analysed using electron tomography. Using this method, electron microscope images of a structure are recorded from many different angles, in a similar way to the process used in medical computed tomography. The individual images can then be combined on the computer to give a high-resolution three-dimensional image – of a synapse in this case (see image).

"Our results showed that readily releasable vesicles in healthy synapses touch the cell membrane," explains Cooper. "However, if Munc13 and CAPS proteins are missing, the vesicles do not reach the active zone and accumulate a few nanometres away from it." To their astonishment, the researchers also observed that SNARE proteins, which collaborate with Munc13 and CAPS in the nerve endings, are also involved in this docking process. SNARE proteins are found in the cell and vesicle membranes of healthy synapses and control the fusion of the two membranes during neurotransmitter release. When a vesicle approaches the cell membrane, the individual SNARE molecules line up opposite each other like the sides of a zip and pull the membranes close to each other in this way. The vesicles await the starting gun for their fusion in this state – in the starting blocks, so to speak.

The findings of the neurobiologists in Göttingen prove that Munc13, CAPS and SNARE proteins closely align the vesicle and cell membrane in the synapse, long before the signal for fusion is given. This is the only way that the fast and controlled transmission of information at the synapse can be guaranteed, thanks to which we can react specifically to information from our environment. "It had long been clear that synapses have to be extremely fast to carry out all of the many complex brain functions. Our study shows for the first time how this is managed at the molecular level and on the level of the synaptic vesicles," says Brose. Because almost all of the protein components involved in this process also play a role in neurological and psychiatric diseases, the Göttingen-based scientists believe that their discovery will soon benefit medical research.

INFORMATION:Original publication:

Imig, C., Min, S.-W., Krinner, S., Arancillo, M., Rosenmund, C., Südhof, T.C., Rhee, J.-S., Brose, N. and Cooper, B.H. (2014) The morphological and molecular nature of synaptic vesicle priming at presynaptic active zones. Neuron 84, 416-431.

Synapses always on the starting blocks

Vesicles filled with neurotransmitters touch the cell membrane, thereby enabling their rapid-fire release

2014-10-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Satellite movie shows Tropical Storm Ana headed to British Columbia, Canada

2014-10-27

VIDEO:

This animation of NOAA's GOES-West satellite imagery from Oct. 1 -27 shows the movement of Tropical Storm Ana as it heads toward British Columbia, Canada. TRT: 00:20.

Click here for more information.

An animation of imagery from NOAA's GOES-West satellite taken over the period of Oct.19 to 26 shows the movement, intensification, weakening and movement toward British Columbia, Canada. On Oct. 27, wind warnings were posted along some coastal sections of British Columbia.

During ...

Prostate cancer, kidney disease detected in urine samples on the spot

2014-10-27

When you flush the toilet, you may be discarding microscopic warning signs about your health.

But a cunningly simple new device can stop that vital information from "going to waste."

Brigham Young University chemist Adam Woolley and his students made a device that can detect markers of kidney disease and prostate cancer in a few minutes. All you have to do is drop a sample into a tiny tube and see how far it goes.

That's because the tube is lined with DNA sequences that will latch onto disease markers and nothing else. Urine from someone with a clean bill of health ...

Lack of transcription factor FoxO1 triggers pulmonary hypertension

2014-10-27

This news release is available in German.

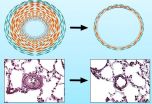

Pulmonary hypertension is characterised by uncontrolled division of cells in the blood vessel walls. As a result, the vessel walls become increasingly thick.

Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Heart and Lung Research in Bad Nauheim and Giessen University have discovered that transcription factor FoxO1 regulates the division of cells and plays a key role in the development of pulmonary hypertension. The researchers were able to cure pulmonary hypertension in rats by activating FoxO1. The study findings could ...

Study documents millions in unused medical supplies in US operating rooms each year

2014-10-27

A Johns Hopkins research team reports that major hospitals across the U.S. collectively throw away at least $15 million a year in unused operating room surgical supplies that could be salvaged and used to ease critical shortages, improve surgical care and boost public health in developing countries.

A report on the research, published online Oct. 16 in the World Journal of Surgery, highlights not only an opportunity for U.S. hospitals to help relieve the global burden of surgically treatable diseases, but also a means of reducing the cost and environmental impact of medical ...

Syracuse physicists closer to understanding balance of matter, antimatter in universe

2014-10-27

Physicists in Syracuse University's College of Arts and Sciences have made important discoveries regarding Bs meson particles—something that may explain why the Universe contains more matter than antimatter.

Distinguished Professor Sheldon Stone and his colleagues recently announced their findings at a workshop at CERN in Geneva, Switzerland. Titled "Implications of LHCb Measurements and Their Future Prospects," the workshop enabled him and other members of the Large Hadron Collider beauty (LHCb) Collaboration to share recent data results.

The LHCb Collaboration ...

Discovery of how newborn mice repair bone fractures could improve treatments

2014-10-27

If you've ever broken a bone, there's a good chance you needed surgery, braces, or splints to realign the bone. Severe fractures in infants, on the other hand, can heal on their own through a process that has eluded scientists. A study published by Cell Press on October 27 in Developmental Cell reveals that a fractured arm bone in newborn mice can rapidly realign through a previously unknown mechanism involving bone growth and muscle contraction. The findings provide new insights into how human infants and other young vertebrates may repair broken bones and pave the way ...

Ibuprofen better choice to relieve fracture pain in children than oral morphine

2014-10-27

Although Ibuprofen and oral morphine both provide effective pain relief for children with broken limbs, ibuprofen is the recommended choice because of adverse events associated with oral morphine, according to a randomized trial published in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal)

Fractures make up between 10% and 25% of all children's injuries, and the most severe pain is felt during the first 48 hours after the injury. Because of concerns about the safety of codeine for children, there is limited choice for medications to relieve pain for these patients.

"Evidence ...

New prostate cancer screening guideline recommends not using PSA test

2014-10-27

A new Canadian guideline recommends that the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test should not be used to screen for prostate cancer based on evidence that shows an increased risk of harm and uncertain benefits. The guideline is published in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal)

"Some people believe men should be screened for prostate cancer with the PSA test but the evidence indicates otherwise," states Dr. Neil Bell, member of the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care and chair of the prostate cancer guideline working group. "These recommendations balance ...

Imaging the genome: Cataloguing the fundamental processes of life

2014-10-27

The team of researchers, led by Dr Rafael Carazo Salas from the Department of Genetics, combined high-resolution 3D confocal microscopy and computer-automated analysis of the images to survey the fission yeast genome with respect to three key cellular processes simultaneously: cell shape, microtubule organisation and cell cycle progression. Microtubules are small, tube-like structures which help cells divide and give them their structure.

Of the 262 genes whose functions the team report in a study published today in the journal Developmental Cell, two-thirds are linked ...

New RCT: KoACT® beats calcium and vitamin D for optimal bone strength

2014-10-27

ity of Industry, CA – October 28, 2014 – A new randomized controlled trial (RCT) of post-menopausal women demonstrates that a proprietary blend of collagen and calcium, KoACT®, was far superior to calcium and vitamin D in slowing down the leaching of calcium from bones and rebuilding new bone strength. An Abstract of the article appears on PubMed at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25314004, ahead of print in The Journal of Medicinal Food.

The research was conducted by Bahram H. Arjmandi, PhD, RDN, who is currently Margaret A. Sitton Named Professor ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

GLP-1 drugs associated with reduced need for emergency care for migraine

New knowledge on heritability paves the way for better treatment of people with chronic inflammatory bowel disease

Under the Lens: Microbiologists Nicola Holden and Gil Domingue weigh in on the raw milk debate

Science reveals why you can’t resist a snack – even when you’re full

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

[Press-News.org] Synapses always on the starting blocksVesicles filled with neurotransmitters touch the cell membrane, thereby enabling their rapid-fire release