(Press-News.org) WASHINGTON, D.C., October 28, 2014 – If you've ever gone for a spin in a luxury car and felt your back being warmed or cooled by a seat-based climate control system, then you've likely experienced the benefits of a class of materials called thermoelectrics. Thermoelectric materials convert heat into electricity, and vice versa, and they have many advantages over more traditional heating and cooling systems.

Recently, researchers have observed that the performance of some thermoelectric materials can be improved by combining different solid phases -- more than one material intermixed like the clumps of fat and meat in a slice of salami. The observations offer the tantalizing prospect of significantly boosting thermoelectrics' energy efficiency, but scientists still lack the tools to fully understand how the bulk properties arise out of combinations of solid phases.

Now a research team based at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) has developed a new way to analyze the electrical properties of thermoelectrics that have two or more solid phases. The new technique could help researchers better understand multi-phase thermoelectric properties – and offer pointers on how to design new materials to get the best properties.

The team describes their new technique in a paper published in the journal Applied Physics Letters, from AIP Publishing.

An Old Theory Does a 180

Because it's sometimes difficult to separately manufacture the pure components that make up multi-phase materials, researchers can't always measure the pure phase properties directly. The Caltech team overcame this challenge by developing a way to calculate the electrical properties of individual phases while only experimenting directly with the composite.

"It's like you've made chocolate chip cookies, and you want to know what the chocolate chips and the batter taste like by themselves, but you can't, because every bite you take has both chocolate chips and batter," said Jeff Snyder, a researcher at Caltech who specializes in thermoelectric materials and devices.

To separate the "chips" and "batter" without un-baking the cookie, Snyder and his colleagues turned to a decades old theory, called effective medium theory, and they gave it a new twist.

"Effective medium theory is pretty old," said Tristan Day, a graduate student in Snyder's Caltech laboratory and first author on the APL paper. The theory is traditionally used to predict the properties of a bulk composite based on the properties of the individual phases. "What's new about what we did is we took a composite, and then backed-out the properties of each constituent phase," said Day.

The key to making the reversal work lies in the different way that each part of a composite thermoelectric material responds to a magnetic field. By measuring certain electrical properties over a range of different magnetic field strengths, the researchers were able to tease apart the influence of the two different phases.

The team tested their method on the widely studied thermoelectric Cu1.97 Ag0.03Se, which consists of a main crystal structure of Cu2Se and an impurity phase with the crystal structure of CuAgSe.

Temperature Control of the Future?

Thermoelectric materials are currently used in many niche applications, including air-conditioned car seats, wine coolers, and medical refrigerators used to store temperature-sensitive medicines.

"The definite benefits of using thermoelectrics are that there are no moving parts in the cooling mechanism, and you don't have to have the same temperature fluctuations typical of a compressor-based refrigerator that turns on every half hour, rattles a bit and then turns off," said Snyder.

One of the drawbacks of the thermoelectric cooling systems, however, is their energy consumption.

If used in the same manner as a compressor-based cooling system, most commercial thermoelectrics would require approximately 3 times more energy to deliver the same cooling power. Theoretical analysis suggests the energy efficiency of thermoelectrics could be significantly improved if the right material combinations and structures were found, and this is one area where Synder and his colleagues' new calculation methods may help.

Many of the performance benefits of multi-phase thermoelectrics may come from quantum effects generated by micro- and nano-scale structures. The Caltech researchers' calculations make classical assumptions, but Snyder notes that discrepancies between the calculations and observed properties could confirm nanoscale effects.

Snyder also points out that while thermoelectrics may be less energy efficient than compressors, their small size and versatility mean they could be used in smarter ways to cut energy consumption. For example, thermoelectric-based heaters or coolers could be placed in strategic areas around a car, such as the seat and steering wheel. The thermoelectric systems would create the feeling of warmth or coolness for the driver without consuming the energy to change the temperature of the entire cabin.

"I don't know about you, but when I'm uncomfortable in a car it's because I'm sitting on a hot seat and my backside is hot," said Snyder. "In principle, 100 watts of cooling on a car seat could replace 1000 watts in the cabin."

Ultimately, the team would like to use their new knowledge of thermoelectrics to custom design 'smart' materials with the right properties for any particular application.

"We have a lot of fun because we think of ourselves as material engineers with the periodic table and microstructures as our playgrounds," Snyder said.

INFORMATION:

The article, "Determining conductivity and mobility values of individual components in multiphase composite Cu1.97 Ag0.03Se," is authored by Tristan W. Day, Wolfgang G. Zeier, David R. Brown, Brent C. Melot, and G. Jeffrey Snyder. It will be published in the journal Applied Physics Letters on October 28, 2014 (DOI: 10.1063/1.4897435). After that date, it can be accessed at: http://scitation.aip.org/content/aip/journal/apl/105/17/10.1063/1.4897435

The authors of this paper are affiliated with the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) and the University of Southern California.

ABOUT THE JOURNAL

Applied Physics Letters features concise, rapid reports on significant new findings in applied physics. The journal covers new experimental and theoretical research on applications of physics phenomena related to all branches of science, engineering, and modern technology. See: http://apl.aip.org

Experiments on the DIII-D tokamak that General Atomics operates for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) have demonstrated the ability of lithium injections to transiently double the temperature and pressure at the edge of the plasma and delay the onset of instabilities and other transients. Researchers conducted the experiments using a lithium- injection device developed at the DOE's Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL).

Lithium can play an important role in controlling the edge region and hence the evolution of the entire plasma. For example, researchers have ...

NASA's Terra satellite passed over Tropical Storm Hanna on Oct. 27 when it made landfall near the northern Nicaragua and southern Honduras border.

On Oct. 27 at 16:00 UTC (12 p.m. EDT) the MODIS instrument aboard NASA's Terra satellite captured a visible image of Tropical Storm Hanna straddling the border between Honduras and Nicaragua. The image, created by NASA's MODIS Rapid Response Team at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, showed strong thunderstorms on both sides of the border, bringing heavy rainfall to those area.

At 10 a.m. EDT on Oct. ...

Scientists from North America, Europe and China have published a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that reveals important details about key transitions in the evolution of plant life on our planet.

From strange and exotic algae, mosses, ferns, trees and flowers growing deep in steamy rainforests to the grains and vegetables we eat and the ornamental plants adorning our homes, all plant life on Earth shares over a billion years of history.

"Our study generated DNA sequences from a vast number of distantly related plants, and we developed new ...

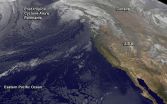

NOAA's GOES-West satellite captured an image of post-tropical cyclone Ana's remnant clouds raining on British Columbia, Canada today, Oct. 28. Wind warnings along some coastal sections of British Columbia continued today as the storm moved through the region.

NOAA's GOES-West satellite gathered infrared data on Ana's remnant clouds and that data was made into an image by NASA/NOAA's GOES Project at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. In the image the remnant clouds resemble a frontal system.

Environment Canada's Meteorological Service continued ...

Asthma, which inflames and narrows the airways, has become more common in recent years. While there is no known cure, asthma can be managed with medication and by avoiding allergens and other triggers. A new study by a Tel Aviv University researcher points to a convenient, free way to manage acute asthmatic episodes — catching some rays outside.

According to a paper recently published in the journal Allergy, measuring and, if need be, boosting Vitamin D levels could help manage asthma attacks. The research, conducted by Dr. Ronit Confino-Cohen of TAU's Sackler Faculty ...

Recent fusion experiments on the DIII-D tokamak at General Atomics (San Diego) and the Alcator C-Mod tokamak at MIT (Cambridge, Massachusetts), show that beaming microwaves into the center of the plasma can be used to control the density in the center of the plasma, where a fusion reactor would produce most of its power. Several megawatts of microwaves mimic the way fusion reactions would supply heat to plasma electrons to keep the "fusion burn" going.

The new experiments reveal that turbulent density fluctuations in the inner core intensify when most of the heat goes ...

When researchers at General Electric Co. sought help in designing a plasma-based power switch, they turned to the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL). The proposed switch, which GE is developing under contract with the DOE's Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy, could contribute to a more advanced and reliable electric grid and help to lower utility bills.

The switch would consist of a plasma-filled tube that turns current on and off in systems that convert the direct current (DC) coming from long-distance power lines to the ...

One out of every five new cancer patients is diagnosed with a rare cancer, yet the clinical evidence needed to effectively treat these rare cancer patients is scarce. Indeed, conventional cancer clinical trial methodologies require large numbers of patients who are difficult to accrue in the situation of rare cancers. Consequently, building clinical evidence for the treatment of rare cancers is more difficult than it is for frequent cancers.

Dr. Jan Bogaerts, EORTC Methodology Vice Director, points out, "For rare cancers, we need alternative ways to conceive study designs ...

A study by the University of Southampton has found there are far fewer women studying economics than men, with women accounting for just 27 per cent of economics students, despite them making up 57 per cent of the undergraduate population in UK universities.

The findings suggest less than half as many girls (1.2 per cent) as boys (3.8 percent) apply to study economics at university, while only 10 per cent of females enrol at university with an A level in maths, compared to 19 per cent of males.

"This underrepresentation of women economics degrees could have major implications ...

A solution to one of the key challenges in the development of quantum technologies has been proposed by University of Sussex physicists.

In a paper published today (28 October) in Nature Communications, Professor Barry Garraway and colleagues show how to make a new type of flexibly designed microscopic trap for atoms.

Quantum technology devices, such as high-precision sensors and specialised superfast computers, often depend on harnessing the delicate interaction of atoms. But the methods for trapping these tiny particles are hugely problematic because of the atoms' ...