(Press-News.org) This news release is available in German.

Children and chimpanzees often follow the group when they want to learn something new. But do they actually forego their own preferences in order to fit in with their peers? In direct comparisons between apes and children, a research team from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig and Jena University has found that the readiness to abandon preferences and conform to others is particularly pronounced in humans – even in two-year-old children. Interestingly, the number of peers presenting an alternative solution appeared to have no influence on whether the children conformed.

From the playground to the boardroom, people often adapt their behaviour to those around them in order to fit in with a particular group. In humans, this conformity appears in childhood, but it is not evidenced in chimpanzees or orangutans. "Conformity plays a central role in human social behaviour, defining and delimiting different groups and helping them coordinate their activities. It stabilizes and promotes cultural diversity, one of the characteristic features of the human species", says psychologist Daniel Haun of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, who headed the study.

This is not to say that it is always best to comply with the majority. Conformity can be good or bad, helpful or unhelpful, appropriate or inappropriate, for both the individual and the group. "The fact is that we often do conform, and our social structure would be completely different if this were not the case. Our study shows that children as young as two adapt their behaviour to fit in, while chimpanzees and orangutans stick with what they know", says Haun.

In an earlier study, Haun and his colleagues found that children and chimpanzees rely on the majority opinion when they are learning something new. This makes a lot of sense, as the group has knowledge that the individual may not be aware of. However, other studies show that human adults sometimes conform even when they already have the relevant knowledge, just to avoid standing out from the crowd. To find out whether young children and apes also show this "normative" conformity, Haun and his co-authors Michael Tomasello and Yvonne Rekers presented two-year-old children, chimpanzees and orangutans with a similar task.

In these experiments, the children and apes were to drop a ball into a box that contained three separate sections. Only one of these sections delivered a reward: a peanut for the apes, and a chocolate drop for the children.

After familiarizing themselves with the box, each participant then watched while several peers deposited their balls into a different section from the one the participant associated with a reward. When it was the participant's turn again, he or she had to choose a section while the other three children looked on.

The results revealed that the children were more likely to adjust their behaviour to that of their peers than were the apes. The children conformed more than half the time, while the chimpanzees and orangutans practically ignored their peers and stuck to their learned strategy.

A follow-up study with two-year-olds showed that children were more likely to switch their choice when observed by their peers, but stayed with their original strategy when left alone. It is interesting to note that participants showed the same propensity to conform independently of whether the alternative was presented by one or three peers. This conformity among toddlers shows that the motivation to fit in emerges very early in humans. "We were surprised to find that children as young as two change their behaviour to avoid the potential disadvantage of being different", says Haun.

The researchers are currently investigating the impact of environmental factors, such as schooling and different child-rearing methods, on children's tendency to conform.

INFORMATION:

Daniel B.M. Haun, Yvonne Rekers, and Michael Tomasello

Children Conform to the Behavior of Peers; Other Great Apes Stick With What They Know

Psychological Science, online advance publication 29 October 2014 (doi: 10.1177/0956797614553235)

Forestry experts of the French Institute for Agricultural Research INRA together with technicians from NEIKER-Tecnalia and the Chartered Provincial Council of Bizkaia felled radiata pine specimens of different ages in order to find out their resistance to gales and observe the force the wind needs to exert to blow down these trees in the particular conditions of the Basque Country.

This experience is of great interest for the managers of forests and will help them to manage their woodlands better and incorporate the wind variable into decisions like the distribution ...

A University of Tennessee, Knoxville, study finds that nonprofit organizations aiming to protect biodiversity show little evidence of responding to economic signals, which could limit the effectiveness of future conservation efforts.

The study is published this week in the academic journal Ecology and Evolution and can be read at http://bit.ly/1t8fT24.

The relationship between economic conditions and conservation efforts is complicated. On the one hand, funding for conservation depends on a booming economy, which swells state coffers and increases membership dues, ...

Only forty per cent of the notable increase in autism cases that has been registered during the past few decades is due to causes that are as yet unknown.

The majority of the increase – a total of sixty per cent – can now be explained by two combined factors: changes in the diagnostic criteria and in the registration to the national health registers.

This is shown by a new study of disease prevalence among all individuals born in Denmark in the period 1980-1991, a total of 677,915 individuals.

The results have recently been published in the medical journal ...

If you can uniformly break the symmetry of nanorod pairs in a colloidal solution, you're a step ahead of the game toward achieving new and exciting metamaterial properties. But traditional thermodynamic -driven colloidal assembly of these metamaterials, which are materials defined by their non-naturally-occurring properties, often result in structures with high degree of symmetries in the bulk material. In this case, the energy requirement does not allow the structure to break its symmetry.

In a study led by Xiang Zhang, director of Berkeley Lab's Materials Sciences ...

Researchers at the University of Cambridge have managed to reconstruct the early stage of mammalian development using embryonic stem cells, showing that a critical mass of cells – not too few, but not too many – is needed for the cells to being self-organising into the correct structure for an embryo to form.

All organisms develop from embryos: a cell divides generating many cells. In the early stages of this process, all cells look alike and tend to aggregate into a featureless structure, more often than not a ball. Then, the cells begin to 'specialise' into ...

Los Angeles, CA (November 4, 2014) How does an individual's happiness level reflect societal conditions? A new article out today in the first issue of Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences (PIBBS) finds that similar to how GDP measures the effectiveness of economic policies, happiness can and should be used to evaluate the effectiveness of social policies.

Authors Shigehiro Oishi and Ed Diener examined research evaluating the effectiveness of policy related to unemployment rate, tax rate, child care, and environmental issues to determine if it's possible ...

Los Angeles, CA (November 4, 2014) The growing disparity in economic inequality has become so stark that even Janet Yellen, Federal Reserve chairwoman, recently expressed concern. Interestingly, new research has discovered that American citizens desire an unequal, but more equal distribution of wealth and income. Lower levels of this "unequality" are associated with decreased unethical behavior and increased motivation and labor productivity. This study is published today in the inaugural issue of Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences (PIBBS).

"People ...

Los Angeles, CA (November 4, 2014) With so much attention to curriculum and teaching skills to improve student achievement, it may come as a surprise that something as simple as how a classroom looks could actually make a difference in how students learn. A new analysis finds that the design and aesthetics of school buildings and classrooms has surprising power to impact student learning and success. The paper is published today in the inaugural issue of Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences (PIBBS).

Surveying the latest scientific research, Sapna Cheryan, ...

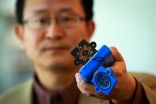

SALT LAKE CITY, Nov. 4, 2014 – University of Utah engineers have developed a new type of carbon nanotube material for handheld sensors that will be quicker and better at sniffing out explosives, deadly gases and illegal drugs.

A carbon nanotube is a cylindrical material that is a hexagonal or six-sided array of carbon atoms rolled up into a tube. Carbon nanotubes are known for their strength and high electrical conductivity and are used in products from baseball bats and other sports equipment to lithium-ion batteries and touchscreen computer displays.

Vaporsens, ...

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — We celebrate our triumphs over adversity, but let's face it: We'd rather not experience difficulty at all. A new study ties that behavioral inclination to learning: When researchers added a bit of conflict to make a learning task more difficult, that additional conflict biased learning by reducing the influence of reward and increasing the influence of aversion to punishment.

This newly found relationship between conflict and reinforcement learning suggests that the circuits in the frontal cortex that calculate the degree of ...