Using robotic ocean gliders, Caltech researchers have now found that swirling ocean eddies, similar to atmospheric storms, play an important role in transporting these warm waters to the Antarctic coast--a discovery that will help the scientific community determine how rapidly the ice is melting and, as a result, how quickly ocean levels will rise.

Their findings were published online on November 10 in the journal Nature Geoscience.

"When you have a melting slab of ice, it can either melt from above because the atmosphere is getting warmer or it can melt from below because the ocean is warm," explains lead author Andrew Thompson, assistant professor of environmental science and engineering. "All of our evidence points to ocean warming as the most important factor affecting these ice shelves, so we wanted to understand the physics of how the heat gets there."

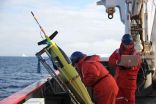

Ordinarily when oceanographers like Thompson want to investigate such questions, they use ships to lower instruments through the water or they collect ocean temperature data from above with satellites. These techniques are problematic in the Southern Ocean. "Observationally, it's a very hard place to get to with ships. Also, the warm water is not at the surface, making satellite observations ineffective," he says.

Because the gliders are small--only about six feet long--and are very energy efficient, they can sample the ocean for much longer periods than large ships can. When the glider surfaces every few hours, it "calls" the researchers via a mobile phone-like device located on the tail. This communication allows the researchers to almost immediately access the information the glider has collected.

Like airborne gliders, the bullet-shaped ocean gliders have no propeller; instead they use batteries to power a pump that changes the glider's buoyancy. When the pump pushes fluid into a compartment inside the glider, the glider becomes denser than seawater and less buoyant, thus causing it to sink. If the fluid is pumped instead into a bladder on the outside of the glider, the glider becomes less dense than seawater--and therefore more buoyant--ultimately rising to the surface. Like airborne gliders, wings convert this vertical lift into horizontal motion.

Thompson and his colleagues from the University of East Anglia dropped their gliders into the ocean off the coast of the Antarctic Peninsula in January 2012; the robotic vehicles then spent the next two months moving up and down through the water column--diving a kilometer below the surface of the water and back up again every few hours--exploring the Weddell Sea off the coast of Antarctica. As the gliders traveled, they collected temperature and salinity data at different locations and depths of the sea.

The glider's up and down capability is important for studying ocean stratification, or how water characteristics, such as density, change with depth, Thompson says. "If it was only temperature that determined density, you'd always have warm water at the top and cold water at the bottom. But in the ocean you also have to factor in salinity; the higher the salinity is in the water, the more dense that water is and the more likely it is to sink to the bottom," he says.

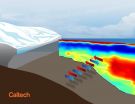

In Antarctica the combined effects of temperature and salinity create an interesting situation, in which the warmest water is not on top, but actually sandwiched in the middle layers of the water column. "That's an additional problem in understanding the heat transport in this region," he adds. You can't just take measurements at the surface, he says. "You actually need to be taking a look at that very warm temperature layer, which happens to sit in the middle of the water column. That's the layer that is actually moving toward the ice shelf."

The results from the gliders revealed that the heat was actually coming from a less predictable source: eddies, swirling underwater storms that are caused by ocean currents.

"Eddies are instabilities that are caused by ocean currents, and we often compare their effect on the ocean to putting a spoon in your coffee," Thompson says. "If you pour milk in your coffee and then you stir it with a spoon, the spoon enhances your ability to mix the milk into the coffee and that is what these eddies do. They are very good at mixing heat and other properties."

Because the gliders could dive and surface every few hours and remain at sea for months, they were able to see these eddies in action--something that ships and satellites had previously been unable to capture.

"Ocean currents are variable, and so if you go just one time, what you measure might not be what the current looks like a day later. It's sort of like the weather--you know it's going to be warm in the summer and cold in the winter, but on a day-to-day basis it could be cold in the summer just because a storm came in," Thompson says. "Eddies do the same thing in the ocean, so unless you understand how the temperature of currents is changing from day to day--information we can actually collect with the gliders--then you can't understand what the long-term heat transport is."

In future work, Thompson plans to couple meteorological data with the data collected from his gliders. In December, the team will use ocean gliders to study a rough patch of ocean between the southern tip of South America and Antarctica, called the Drake Passage, as a surface robot, called a Waveglider, collects information from the surface of the water. "With the Waveglider, we can measure not just the ocean properties, but atmospheric properties as well, such as wind speed and wind direction. So we'll get to actually see what's happening at the air-sea interface."

In the Drake Passage, deep waters from the Southern Ocean are "ventilated"--or emerge at the surface--a phenomenon specific to this region of the ocean. That makes the location important for understanding the exchange of carbon dioxide between the atmosphere and the ocean. "The Southern Ocean is the window through which deep waters can actually come up to 'see' the atmosphere"--and it's also a window for oceanographers to more easily see the deep ocean, he says. "It's a very special place for many reasons."

INFORMATION:

The work with ocean gliders was published in a paper titled "Eddy transport as a key component of the Antarctic overturning circulation." Other authors on the paper include Karen J. Heywood of the University of East Anglia, Sunke Schmidtko of GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research-Kiel, and Andrew Stewart, a former postdoctoral scholar at Caltech who is now at UCLA. Thompson's glider work was supported by an award from the National Science Foundation and the UK's Natural Environment Research Council; Stewart was supported by the President's and Director's Fund program at Caltech.