(Press-News.org) CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Tiny, thin microtubes could provide a scaffold for neuron cultures to grow so that researchers can study neural networks, their growth and repair, yielding insights into treatment for degenerative neurological conditions or restoring nerve connections after injury.

Researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and the University of Wisconsin-Madison created the microtube platform to study neuron growth. They posit that the microtubes could one day be implanted like stents to promote neuron regrowth at injury sites or to treat disease.

"This is a powerful three-dimensional platform for neuron culture," said Xiuling Li, U. of I. professor of electrical and computer engineering who co-led the study along with UW-Madison professor Justin Williams. "We can guide, accelerate and measure the process of neuron growth, all at once."

The team published the results in the journal ACS Nano.

"There are a lot of diseases that are very difficult to figure out the mechanisms of in the body, so people grow cultures on platforms so we can see the dynamics under a microscope," said U. of I. graduate student Paul Froeter, the first author of the study. "If we can see what's happening, hopefully we can figure out the cause of the deficiency and remedy it, and later integrate that into the body."

The biggest challenge facing researchers trying to culture neurons for study is that it's very difficult to recreate the cozy, soft, three-dimensional environment of the brain. Other techniques have used glass plates or channels carved into hard slabs of material, but the nerve cells look and behave differently than they would in the body. The microtubes provide a three-dimensional, pliant scaffolding, the way that the cellular matrix does in the body.

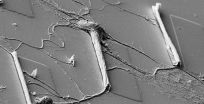

The team uses an array of microtubes, made with a technique pioneered in Li's lab for electronics applications such as 3-D inductors. Very thin membranes of silicon nitride roll themselves up into tubes of precise dimensions. The tubes are about as wide as the cells, as long as a human hair is wide, and spaced apart about as far as they are long. The neurons grow along and through the microtubes, sending out exploratory arms across the gaps to find the next tube.

See a YouTube video of a neuron growing from tube to tube.

Froeter devised a way to mount the microtubes on glass slides, the standard for biological cultures. The thin silicon nitride tubes are transparent, so researchers can watch the live neuron cells as they grow using a conventional microscope.

"Having the ability to see through both the tube and the underlying substrate has been really enlightening," said Williams, a professor of biomedical engineering at UW-Madison. "Without this we may have noticed an overall increase in growth rates, but we never would have observed the dramatic changes that occur as the cells transition from the flat regions to the tube inlets."

The microtubes not only provide structure for the neural network, guiding connections, but also accelerate the nerve cells' growth - and time is crucial for restoring severed connections in the case of spinal cord injury or limb reattachment.

Because they are so thin, the microtubes are flexible enough to wrap around the cells without damaging or flattening them. The researchers found that the axons, the long branches the nerve cells send out to make connections, grow through the microtubes like a sheath - and at up to 20 times the speed of growing across the gaps.

"It's not surprising that the axons like to grow within the tubes," Williams said. "These are exactly the types of spaces where they grow in vivo. What was really surprising was how much faster they grew. This now gives us a powerful investigative tool as we look to further optimize tube structure and geometry."

The microtube arrays can be tuned to any dimensions needed, since nerve cells vary greatly in size from small brain cells to large muscle-controlling nerves. Li and Froeter have already sent microtube arrays of various dimensions to other research groups studying neural networks for diverse applications.

For Li's group, the next step is to put electrodes in the microtubes so researchers can measure the electrical signals that the nerves conduct.

"If we place electrodes inside the tube, since they are directly in contact with the axon, we will be able to study signal conduction much better than conventional methods," Li said.

They also are working to stack the microtubes in multiple layers so that bundles of nerves can grow in a 3-D network.

"If we can grow lines of neurons together in a bundle, we could simulate what's going down your spine or going to your limbs," Froeter said. "Then we can take mature cultures and sever them, then introduce the microtubes and see how they regrow."

"Getting to the clinic will take a long time, but that is what keeps us motivated," Li said.

INFORMATION:

The Andrew T. Yang Research Award, the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health supported this work. Li also is affiliated with the Micro and Nanotechnology Laboratory, the Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory, the department of mechanical science and engineering and the Beckman Institute at the U. of I. Other Illinois authors included bioengineering and cell and developmental biology professor Martha Gillette and graduate students Olivia Cangellaris and Wen Huang. Wisconsin postdoctoral researcher Yu Huang was a co-first author.

Editor's note: To reach Xiuling Li, call 217-265-6354; email xiuling@illinois.edu.

To reach Paul Froeter, email thatfroeterguy@gmail.com. The paper, "Toward Intelligent Synthetic Neural Circuits: Directing and Accelerating Neuron Cell Growth by Self-Rolled-Up Silicon Nitride Microtube Array," is available online at http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/nn504876y.

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - Crop producers and scientists hold deeply different views on climate change and its possible causes, a study by Purdue and Iowa State universities shows.

Associate professor of natural resource social science Linda Prokopy and fellow researchers surveyed 6,795 people in the agricultural sector in 2011-2012 to determine their beliefs about climate change and whether variation in the climate is triggered by human activities, natural causes or an equal combination of both.

More than 90 percent of the scientists and climatologists surveyed said they ...

Located hundreds of miles inland from the nearest ocean, the Midwest is unaffected by North Atlantic hurricanes.

Or is it?

With the Nov. 30 end of the 2014 hurricane season just weeks away, a University of Iowa researcher and his colleagues have found that North Atlantic tropical cyclones in fact have a significant effect on the Midwest. Their research appears in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.

Gabriele Villarini, UI assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering, studied the discharge records collected at 3,090 U.S. Geological Survey ...

COLUMBIA, Mo. - Glycogen storage disorders, which affect the body's ability to process sugar and store energy, are rare metabolic conditions that frequently manifest in the first years of life. Often accompanied by liver and muscle disease, this inability to process and store glucose can have many different causes, and can be difficult to diagnose. Now, researchers at the University of Missouri who have studied enzymes involved in metabolism of bacteria and other organisms have catalogued the effects of abnormal enzymes responsible for one type of this disorder in humans. ...

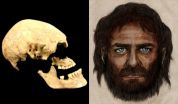

What if you researched your family's genealogy, and a mysterious stranger turned out to be an ancestor?

That's the surprising feeling had by a team of scientists who peered back into Europe's murky prehistoric past thousands of years ago. With sophisticated genetic tools, supercomputing simulations and modeling, they traced the origins of modern Europeans to three distinct populations.

The international research team published their September 2014 results in the journal Nature.

XSEDE, the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment, provided the computational ...

Reston, Va. (November 11, 2014) - A novel study demonstrates the potential of a novel molecular imaging drug to detect and visualize early prostate cancer in soft tissue, lymph nodes and bone. The research, published in the November issue of the Journal of Nuclear Medicine, compares the biodistribution and tumor uptake kinetics of two Tc-99m labeled ligands, MIP-1404 and MIP-1405, used with SPECT and planar imaging.

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed non-skin cancer in the United States, and it is second only to lung cancer as the leading cause of cancer ...

If you're a native of rural Mozambique who contracts HIV and becomes symptomatic, before seeking clinical testing and treatment, you'll likely consult a traditional healer.

Your healer may well conclude that your complaints are caused by a curse, perhaps placed upon you by a neighbor or by the spirit of an ancestor. To help you battle your predicament, the healer will likely cut your skin with a razor blade and rub medicinal herbs into the cut.

A recent survey of symptomatic HIV-positive people in rural Mozambique, led by Carolyn Audet, Ph.D., M.A., assistant professor ...

New research from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health suggests that HIV-infected adults are at a higher risk for developing heart attacks, kidney failure and cancer. But, contrary to what many had believed, the researchers say these illnesses are occurring at similar ages as adults who are not infected with HIV.

The findings appeared online last month in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases.

Researchers say these findings can help reassure HIV-infected patients and their health care providers.

"We did not find conclusive evidence to suggest that ...

New Haven, Conn.--The phrase "tears of joy" never made much sense to Yale psychologist Oriana Aragon. But after conducting a series of studies of such seemingly incongruous expressions, she now understands better why people cry when they are happy.

"People may be restoring emotional equilibrium with these expressions," said Aragon, lead author of work to be published in the journal Psychological Science. "They seem to take place when people are overwhelmed with strong positive emotions, and people who do this seem to recover better from those strong emotions."

There ...

With both wolf proposals shot down by Michigan voters on election day, the debate over managing and hunting wolves is far from over.

A Michigan State University study, appearing in a recent issue of the Journal of Wildlife Management, identifies the themes shaping the issue and offers some potential solutions as the debate moves forward.

The research explored how different sides of the debate view power imbalances among different groups and the role that scientific knowledge plays in making decisions about hunting wolves. These two dimensions of wildlife management ...

PHILADELPHIA (Nov. 11, 2014) - Federal laws explicitly addressing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have overwhelmingly focused on the needs of military personnel and veterans, according to a new analysis published in the Journal of Traumatic Stress.

The study, authored by Jonathan Purtle, DrPH, an assistant professor at the Drexel University School of Public Health, is the first to examine how public policy has been used to address psychological trauma and PTSD in the U.S., providing a glimpse of how lawmakers think about these issues.

Purtle found that in federal ...