HIV virulence depends on where virus inserts itself in host DNA

Retargeting integration site to 'safer' part of host DNA may lead to new therapies

2014-11-12

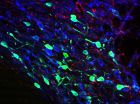

(Press-News.org) The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can insert itself at different locations in the DNA of its human host - and this specific integration site determines how quickly the disease progresses, report researchers at KU Leuven's Laboratory for Molecular Virology and Gene Therapy. The study was published online today in the journal Cell Host & Microbe.

When HIV enters the bloodstream, virus particles bind to and invade human immune cells. HIV then reprogrammes the hijacked cell to make new HIV particles.

The HIV protein integrase plays a key role in this process: it recognises a short segment in the DNA of its host and catalyzes the process by which viral DNA is inserted in host DNA.

Integrase can insert viral DNA at various places in human DNA. But how the virus selects its insertion points has puzzled virologists for over 20 years.

Now a team of KU Leuven researchers has discovered that the answer lies in two amino acids. Doctoral researcher Jonas Demeulemeester, first author of the study, explains: "HIV integrase is made up of a chain of more than 200 amino acids folded into a structure. By modelling this structure, we found two positions in the protein that make direct contact with the DNA of the host. These two amino acids determine the integration site. This is not only the case for HIV but also for related animal-borne viruses."

In a second phase of the study, the researchers were able to manipulate the integration site choice of HIV, explains Professor Rik Gijsbers. "We changed the specific HIV integrase amino acids for those of animal-borne viruses and found that the viral DNA integrated in the host DNA at locations where the animal-borne virus normally would have done so."

"We also showed that HIV integrases can vary," says Professor Rik Gijsbers. "Sometimes different amino acids appeared in the two positions we identified. These variant viruses also integrate into the host DNA at a different site than the normal virus does."

Together with Dr. Thumbi Ndung'u (University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa), the team studied the impact of these viral variants on the progression towards AIDS in a cohort of African HIV patients, continues Professor Zeger Debyser: "To our surprise, we found that the disease progressed more quickly when the integration site was changed. In other words, the variant viruses broke down the immune system more rapidly. This insight both increases our knowledge of the disease and opens new perspectives. By retargeting the integration site to a 'safer' part of the host DNA, we hope to eventually develop new therapies."

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2014-11-12

Details of the role of glutamate, the brain's excitatory chemical, in a drug reward pathway have been identified for the first time.

This discovery in rodents - published today in Nature Communications - shows that stimulation of glutamate neurons in a specific brain region (the dorsal raphe nucleus) leads to activation of dopamine-containing neurons in the brain's reward circuit (dopamine reward system).

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter present in regions of the brain that regulate movement, emotion, motivation, and feelings of pleasure. Glutamate is a neurotransmitter ...

2014-11-12

HANOVER, N.H. - China's anti-logging, conservation and ecotourism policies are accelerating the loss of old-growth forests in one of the world's most ecologically fragile places, according to studies led by a Dartmouth College scientist.

The findings shed new light on the complex interactions between China's development and conservation policies and their impact on the most diverse temperate forests in the world, in "Shangri-La" in northwest Yunnan Province. Shangri-La, until recently an isolated Himalayan hinterland, is now the epicenter of China's struggle to wed sustainable ...

2014-11-12

The "surfactant" chemicals found in samples of fracking fluid collected in five states were no more toxic than substances commonly found in homes, according to a first-of-its-kind analysis by researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Fracking fluid is largely comprised of water and sand, but oil and gas companies also add a variety of other chemicals, including anti-bacterial agents, corrosion inhibitors and surfactants. Surfactants reduce the surface tension between water and oil, allowing for more oil to be extracted from porous rock underground.

In a new ...

2014-11-12

Action movies may drive box office revenues, but dramas and deeper, more serious movies earn audience acclaim and appreciation, according to a team of researchers.

"Most people think that entertainment is just a silly diversion, but our research shows that entertainment is profoundly meaningful and moving for many people," said Mary Beth Oliver, Distinguished Professor in Media Studies and co-director of Media Effects Research Laboratory, Penn State. "It's not just types of entertainment that we usually think of as meaningful, such as poetry and dance, either, but also ...

2014-11-12

Shark populations in the Mediterranean are highly divided, an international team of scientists, led by Dr Andrew Griffiths of the University of Bristol, has shown. Many previous studies on sharks suggest they move over large distances. But catsharks in the Mediterranean Sea appear to move and migrate much less, as revealed by this study. This could have important implications for conserving and managing sharks more widely, suggesting they may be more vulnerable to over-fishing than previously thought.

The study, published in the new journal Royal Society Open Science, ...

2014-11-12

Providing health information on the internet may not be the "cure all" that it is hoped to be. It could sideline especially those Americans older than 65 years old who are not well versed in understanding health matters, and who do not use the web regularly. So says Helen Levy of the University of Michigan in the US, who led the first-ever study to show that elderly people's knowledge of health matters, so-called health literacy, also predicts how and if they use the internet. The findings¹ appear in the Journal of General Internal Medicine², published by Springer.

Substantial ...

2014-11-12

Learning a new language changes your brain network both structurally and functionally, according to Penn State researchers.

"Learning and practicing something, for instance a second language, strengthens the brain," said Ping Li, professor of psychology, linguistics and information sciences and technology. "Like physical exercise, the more you use specific areas of your brain, the more it grows and gets stronger."

Li and colleagues studied 39 native English speakers' brains over a six-week period as half of the participants learned Chinese vocabulary. Of the subjects ...

2014-11-12

The tree has been an effective model of evolution for 150 years, but a Rice University computer scientist believes it's far too simple to illustrate the breadth of current knowledge.

Rice researcher Luay Nakhleh and his group have developed PhyloNet, an open-source software package that accounts for horizontal as well as vertical inheritance of genetic material among genomes. His "maximum likelihood" method, detailed this month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, allows PhyloNet to infer network models that better describe the evolution of certain ...

2014-11-12

Most community-based mental health providers are not well prepared to take care of the special needs of military veterans and their families, according to a new study by the RAND Corporation that was commissioned by United Health Foundation in collaboration with the Military Officers Association of America.

The exploratory report, based on a survey of mental health providers nationally, found few community-based providers met criteria for military cultural competency or used evidence-based approaches to treat problems commonly seen among veterans.

"Our findings suggest ...

2014-11-12

A new study from The University of Texas at Arlington biologists examining non-genetic changes in water flea development suggests something human parents have known for years - ensuring a future generations' success often means sacrifice.

Matthew Walsh, an assistant professor of biology, and his team looked at a phenomenon called "phenotypic plasticity" in the Daphnia abigua, or water flea. Phenotypic plasticity is when an organism changes its trait expressions or physical characteristics, or those of its offspring, because of external factors. In Daphnia, that can mean ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] HIV virulence depends on where virus inserts itself in host DNA

Retargeting integration site to 'safer' part of host DNA may lead to new therapies