(Press-News.org) Plants all over the world are more sensitive to drought than many experts realized, according to a new study by scientists at UCLA and China's Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden. The research will improve predictions of which plant species will survive the increasingly intense droughts associated with global climate change.

The research is reported online by Ecology Letters, the most prestigious journal in the field of ecology, and will be published in an upcoming print edition.

Predicting how plants will respond to climate change is crucial for their conservation. But good predictions require an understanding of plants' ability to acclimate to environmental changes, or their "plasticity." All organisms show some degree of plasticity, but because they're stationary, plants are especially dependent on this ability.

"Plants are masters of plasticity, changing their size, branching patterns, leaf colors and even their internal biochemistry to adjust to changes in climate," said Lawren Sack, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology in the UCLA College and the study's senior author.

Little has been known about the degree to which plastic changes might allow plants to endure worsening droughts.

"Plants have evolved this amazing ability to sync with their environment, but they are facing their limits," said Megan Bartlett, a UCLA doctoral student in ecology and evolutionary biology and the study's lead author.

Compiling and analyzing data for numerous species from various ecosystems around the world, Bartlett found that most species accumulate salts in their cell sap to fine-tune their tolerance to seasonal changes in rainfall. But that adjustment only provides a relatively narrow degree of additional drought tolerance.

Saltier cell sap gives plants the ability to continue to grow as soil dries during drought. Unlike animal cells, plant cells are enclosed by cell walls. To hold up the cell walls, plants depend on "turgor pressure" -- the pressure produced by internal water pushing against the inside of the cell wall. As the cells dehydrate, the turgor pressure declines until the cell walls collapse, and the leaf becomes limp and wilted.

The team of biologists collected data on the "turgor loss point" -- the level of dehydration that causes leaves to wilt. Plants that have a lower turgor loss point can lose more water before wilting, and can keep open their pores, or stomata, to take up carbon dioxide for photosynthesis in drier soils.

"During a drought, plants have to choose between closing their stomata and risking starvation, and continuing to photosynthesize and risking cell damage from wilting," Sack said.

Previous research by the UCLA team revealed the key mechanism plants use to adjust their turgor loss point during drought. Plants load their cells with salts, which attract water molecules and limit turgor loss. In wet conditions, plants invest fewer resources in producing and accumulating these solutes and reduce the saltiness of their cell sap.

Drawing on both new data they produced and previously reported data for hundreds of species, the scientists determined the overall picture of how much plant species adjust their cell sap saltiness to maintain turgor and continue to grow during drought.

"For most plants, these adjustments were small," Sack said. "This means they have only limited wiggle room as droughts become more serious. On the plus side, this discovery means we can estimate species' drought tolerance relatively simply. We can make a reasonable drought tolerance measurement for most species regardless of time of year or whether we are sampling during wet or dry conditions."

Bartlett said the finding is good news for plant biologists. "It means that predicting how a species will respond to climate change from one season of drought tolerance measurements is a reasonable place to start," she said. "Our predictions will be more accurate when we take plasticity into account, but sampling in one season is a reasonable simplification for really diverse ecosystems, like tropical rainforests."

All ecosystems potentially vulnerable

The researchers expected plants' plasticity to be very different based on whether they live in deserts, which may get less than an inch of rainfall per year, or rainforests, which may receive more than 10 feet. Instead, they found relatively small differences across ecosystems, meaning that plants are potentially vulnerable no matter where they live, the scientists said.

The researchers also compared plasticity for crops. They found a strikingly contrasting result: Whereas differences in plasticity among wild species were relatively small and unimportant, among the varieties of certain crop species -- such as coffee and corn -- greater plasticity resulted in improved drought tolerance.

"It's been suspected for a long time that plasticity in cell saltiness might improve crop drought tolerance, so it makes sense that we found impressive differences among crop cultivars and that these differences translate into drought tolerance," Bartlett said. "Our study points to plasticity in turgor loss point as an especially important focus for breeding and selecting drought tolerant cultivars."

INFORMATION:

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation's Graduate Research Fellowship Program and East Asia and Pacific Summer Institute, the Smithsonian Institution's Center for Tropical Forest Science - Forest Global Earth Observatory, the Vavra Research Fellowship and UCLA's department of ecology and evolutionary biology.

MOUNT VERNON, Wash. -- A new study by researchers at Washington State University shows that mechanical harvesting of cider apples can provide labor and cost savings without affecting fruit, juice, or cider quality.

The study, published in the journal HortTechnology in October, is one of several studies focused on cider apple production in Washington State. It was conducted in response to growing demand for hard cider apples in the state and the nation.

Quenching a thirst for cider

Hard cider consumption is trending steeply upward in the region surrounding the food-conscious ...

As our society ages, a University of Montreal study suggests the health system should be focussing on comorbidity and specific types of disabilities that are associated with higher health care costs for seniors, especially cognitive disabilities. Comorbidity is defined as the presence of multiple disabilities. Michaël Boissonneault and Jacques Légaré of the university's Department of Demography came to this conclusion after assessing how individual factors are associated with variation in the public costs of healthcare by studying disabled Quebecers over ...

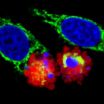

The scientists showed that the Parkin protein functions to repair or destroy damaged nerve cells, depending on the degree to which they are damaged

People living with Parkinson's disease often have a mutated form of the Parkin gene, which may explain why damaged, dysfunctional nerve cells accumulate

Dublin, Ireland, November 13th, 2014 - Scientists at Trinity College Dublin have made an important breakthrough in our understanding of Parkin - a protein that regulates the repair and replacement of nerve cells within the brain. This breakthrough generates a new perspective ...

There are no approved treatments or preventatives against Ebola virus disease, but investigators have now designed peptides that mimic the virus' N-trimer, a highly conserved region of a protein that's used to gain entry inside cells.

The team showed that the peptides can be used as targets to help researchers develop drugs that might block Ebola virus from entering into cells.

"In contrast to the most promising current approaches for Ebola treatment or prevention, which are species-specific, our 'universal' target will enable the selection of broad-spectrum inhibitors ...

In a study of middle-aged men who were overweight, researchers found that if a man's parents were older at the time of his birth, he was more likely to have lower blood pressure, more favorable cholesterol levels, and improved glucose metabolism. It's unknown whether the beneficial effect was due to having an older mother, an older father, or both.

Additional studies are necessary to help shed light on the effects of parental age at childbirth on the metabolism of men and women. "In particular, more research is required to understand whether these effects are due to ...

In a study that looked at what factors might affect whether or not a patient receives intensive medical procedures in the last 6 months of life, investigators found that older age, Alzheimer's disease, cancer, living in a nursing home, and having an advance directive were associated with a lower likelihood of undergoing an intensive procedure. In contrast, living in a region with higher hospital care intensity and black race each doubled a patient's likelihood of undergoing an intensive procedure.

"It's pretty striking the extent to which nonclinical factors--such as ...

Preeclampsia, a late-pregnancy disorder that is characterized by high blood pressure and organ damage, may be caused by problems related to meeting the oxygen demands of the growing fetus, experts say in a new Anaesthesia paper.

Left untreated, preeclampsia can lead to serious--even fatal--complications for a pregnant woman and her baby. The new theory challenges the current view that pre-eclampsia is caused by a problem with the placenta. "When the fetus is not getting enough oxygen and nutrients for its growth--due to conditions in the mother, conditions in the placenta ...

Investigators recently set out to consider whether homicides involving social networking sites were unique and worthy of labels such as 'Facebook Murder', and to explore the ways in which perpetrators had used such sites in the homicides they had committed.

The cases they identified were not collectively unique or unusual when compared with general trends and characteristics--certainly not to a degree that would necessitate the introduction of a new category of homicide or a broad label like 'Facebook Murder'.

"Victims knew their killers in most cases, and the crimes ...

Stanching the free flow of blood from an injury remains a holy grail of clinical medicine. Controlling blood flow is a primary concern and first line of defense for patients and medical staff in many situations, from traumatic injury to illness to surgery. If control is not established within the first few minutes of a hemorrhage, further treatment and healing are impossible.

At UC Santa Barbara, researchers in the Department of Chemical Engineering and at Center for Bioengineering (CBE) have turned to the human body's own mechanisms for inspiration in dealing with the ...

Researchers at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, in collaboration with The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth), Baylor College of Medicine and the Georgia Regents University, report for the first time that the cholesterol-lowering drug simvastatin inhibits the growth of human uterine fibroid tumors. These new data are published online and scheduled to appear in the January print edition of the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Statins, such as simvastatin, are commonly prescribed to lower high cholesterol levels. Statins ...