Pseudomonas is the first pathogen found to initiate infection after merely attaching to the surface of a host, Princeton University and Dartmouth College researchers report in the journal the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. This mechanism means that the bacteria, unlike most pathogens, do not rely on a chemical signal specific to any one host, and just have to make contact with any organism that's ripe for infection.

The researchers found, however, that the bacteria could not infect another organism when a protein on their surface known as PilY1 was disabled. This suggests a possible treatment that, instead of attempting to kill the pathogen, targets the bacteria's own mechanisms for infection.

Corresponding author Zemer Gitai, a Princeton associate professor of molecular biology, explained that the majority of bacteria, viruses and other disease-causing agents depend on "taste," as in they respond to chemical signals unique to the hosts with which they typically co-evolved. Pseudomonas, however, through their sense of touch, are able to thrive on humans, plants, animals, numerous human-made surfaces, and in water and soil. They can cause potentially fatal organ infections in humans, and are the culprit in many hospital-acquired illnesses such as sepsis. The bacteria are largely unfazed by antibiotics.

"Pseudomonas' ability to infect anything was known before. What was not known was how it's able to detect so many types of hosts," Gitai said. "That's the key piece of this research -- by using this sense of touch, as opposed to taste, Pseudomonas can equally identify any kind of suitable host and initiate infection in an attempt to kill it."

The researchers found that only two conditions must be satisfied for Pseudomonas to launch an infection: Surface attachment and "quorum sensing," a common bacterial mechanism wherein the organisms can detect that a large concentration of their kind is present. The researchers focused on the surface-attachment cue because it truly sets Pseudomonas apart, said Gitai, who worked with first author Albert Siryaporn, a postdoctoral researcher in Gitai's group; George O'Toole, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Dartmouth; and Sherry Kuchma, a senior scientist in O'Toole's laboratory.

To demonstrate the bacteria's wide-ranging lethality, Siryaporn infected ivy cells with the bacteria then introduced amoebas to the same sample; Pseudomonas immediately detected and quickly overwhelmed the single-celled animals. "The bacteria don't know what kind of host it's sitting on," Siryaporn said. "All they know is that they're on something, so they're on the offensive. It doesn't draw a distinction between one host or another."

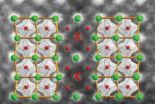

When Siryaporn deleted the protein PilY1 from the bacteria's surface, however, the bacteria lost their ability to infect and thus kill the test host, an amoeba. "We believe that this protein is the sensor of surfaces," Siryaporn said. "When we deleted the protein, the bacteria were still on a surface, but they didn't know they were on a surface, so they never initiated virulence."

Because PilY1 is on a Pseudomonas bacterium's surface and required for virulence, it presents a comprehensive and easily accessible target for developing drugs to treat Pseudomonas infection, Gitai said. Many drugs are developed to target components in a pathogen's more protected interior, he said.

Kerwyn Huang, a Stanford University assistant professor of bioengineering, said that the research is an important demonstration of an emerging approach to treating pathogens -- by disabling rather than killing them.

"This work indicates that the PilY1 sensor is a sort of lynchpin for the entire virulence response, opening the door to therapeutic design that specifically disrupts the mechanical cues for activating virulence," said Huang, who is familiar with the research but had no role in it.

"This is a key example of what I think will become the paradigm in antivirals and antimicrobials in the future -- that trying to kill the microbes is not necessarily the best strategy for dealing with an infection," Huang said. "[The researchers'] discovery of the molecular factor that detects the mechanical cues is critical for designing such compounds."

Targeting proteins such as PilY1 offers an avenue for combating the growing problem of antibiotic resistance among bacteria, Gitai said. Disabling the protein in Pseudomonas did not hinder the bacteria's ability to multiply, only to infect.

Antibiotic resistance results when a drug kills all of its target organisms, but leaves behind bacteria that developed a resistance to the drug. These mutants, previously in the minority, multiply at an astounding rate -- doubling their numbers roughly every 30 minutes -- and become the dominant strain of pathogen, Gitai said. If bacteria had their ability to infect disabled, but were not killed, the mutant organisms would be unlikely to take over, he said.

"I'm very optimistic that we can use drugs that target PilY1 to inhibit the whole virulence process instead of killing off bacteria piecemeal," Gitai said. "This could be a whole new strategy. Really what people should be doing is screening drugs that inhibit virulence but preserve growth. This protein presents a possible route by which to do that."

PilY1 also is found in other bacteria with a range of hosts, Gitai said, including Neisseria gonorrhoeae or the large bacteria genus Burkholderia, which, respectively, cause gonorrhea in humans and are, along with Pseudomonas, a leading cause of lung infection in people with cystic fibrosis. It is possible that PilY1 has a similar role in detecting surfaces and initiating infection for these other bacteria, and thus could be a treatment target.

VIDEO: The video above, captured during a span of 113 minutes, shows that Pseudomonas (gray tubes) grow exponentially -- doubling their numbers roughly every 30 minutes -- and establish large populations...

Click here for more information.

Frederick Ausubel, a professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School, said that the research could help explain how opportunistic pathogens are able to infect multiple types of hosts. Recent research has revealed a lot about how bacteria initiate an infection, particularly via quorum sensing and chemical signals, but the question about how that's done across a spectrum of unrelated hosts has remained unanswered, said Ausubel, who is familiar with the research but had no role in it.

"A broad host-range pathogen such as Pseudomonas cannot rely solely on chemical cues to alert it to the presence of a suitable host," Ausubel said.

"It makes sense that Pseudomonas would use surface attachment as one of the major inputs to activating virulence, especially if attachment to surfaces in general rather than to a particular surface is the signal," he said. "There is probably an advantage to activating virulence only when attached to a host cell, and it is certainly possible that other broad host-range opportunistic pathogens utilize a similar strategy."

INFORMATION:

The paper, "Surface attachment induces Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence," was published online Nov. 10 by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The work was supported by a National Institutes of Health Director's New Innovator Award (grant no. 1DP2OD004389); the National Science Foundation (grant no. 1330288); an NIH National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases postdoctoral fellowship (no. F32AI095002) and grant (no. R37-AI83256-06); and the Human Frontiers in Science Program.