(Press-News.org) China has made significant progress increasing access to tap water and sanitation services, and has sharply reduced the burden of waterborne and water-related infectious diseases over the past two decades. However, in a study published in the latest edition of Nature Climate Change, researchers from Emory University found that climate change will blunt China's efforts at further reducing these diseases in the decades to come.

The study found that by 2030, changes to the global climate could delay China's progress reducing diarrheal and vector-borne diseases by up to seven years. That is, even as China continues to invest in water and sanitation infrastructure, and experience rapid urbanization and social development, the benefits of these advances will be slowed in the presence of climate change.

Using data drawn from multiple infectious disease surveillance systems in China, the study, led by Justin V. Remais, PhD, associate professor of environmental health at Emory's Rollins School of Public Health, provides the first estimates of the burden of disease due to unsafe water, sanitation and hygiene in a rapidly developing society that is subjected to a changing climate.

Remais' team, including colleagues at the University of Florida, the University of Colorado, the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences, found that changes to global temperature can substantially delay China's heretofore rapid progress towards decreasing the burden of diarrheal and vector-borne diseases. The authors accounted for changes in China's population structure, the ongoing migration of China's population, and the country's rapid investment in water and sanitation infrastructure.

"Our results demonstrate how climate change can lead to a significant health burden, even in settings where the total burden of disease is falling owing to social and economic development," says Remais. "Delays in development are especially concerning for China, which is investing heavily in improving health even as the impact of those investments is being countered by the effect of climate change."

Remais and his colleagues present several policy options to limit the impact of climate change on China's infectious disease burden. If China and other major global greenhouse gas emitters take steps to reduce their emissions, the delay in China's development will be shorter, falling to as low as two years. Likewise, if China ramps up its investments in water, sanitation and hygiene infrastructure, the development delay imposed by climate change can be reduced to as low as eight months.

"Our findings show that there are clear ways that China, and the global community, can limit these health effects of climate change, both by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and by investing in health through water and sanitation improvements," says Remais. "Even societies experiencing rapid improvements will be impacted by climate change, and our study highlights how delays in development come at a large cost, and can be avoided if we act now to reduce emissions of climate-changing greenhouse gases."

The authors point out that their analysis focused on only one family of health impacts associated with climate change, and thus the true development delay imposed by climate change on China is likely much larger. They say that policymakers in China must be aware of the health risks--and associated costs--that come with continued increases in greenhouse gas emissions, both within China and globally.

INFORMATION:

The study, 'Delays in reducing waterborne and water-related infectious diseases in China under climate change,' was supported in part by the Emory Global Health Institute.

For the full study, please visit: http://www.nature.com/nclimate/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/nclimate2428.html

Faced with declining enrollment and rising costs, some small liberal arts colleges have added professional and vocational majors, a decision University of Iowa researchers say has strengthened rather than undermined the mission of the schools.

In fact, students at liberal arts colleges realized virtually the same educational gains, no matter their major, according to the UI report released earlier this month. The only differences were liberal arts major expressed a greater interest in literacy while professional majors scored higher in leadership skills.

"Essentially, ...

A collaborative team of leaders in the field of cancer immunology from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center has made a key discovery that advances the understanding of why some patients respond to ipilimumab, an immunotherapy drug, while others do not. MSK was at the forefront of the clinical research that brought this CTLA-4 blocking antibody to melanoma patients.

A report published online first today in the New England Journal of Medicine shows that in patients who respond to ipilimumab, their cancer cells carry a high number of gene mutations--some of which make ...

Barcelona, Spain: Patients with a form of advanced colorectal cancer that is driven by a mutated version of the BRAF gene have limited treatment options available. However, results from a multi-centre clinical trial suggest that the cancer may respond to a combination of three targeted drugs.

Professor Josep Tabernero, head of the medical oncology department at Vall d'Hebron University Hospital and director of the Vall d'Hebron Institute of Oncology, Barcelona, Spain, will tell the 26th EORTC-NCI-AACR [1] Symposium on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics in Barcelona ...

(PHILADELPHIA) - Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig's disease, is a neurodegenerative disease that primarily kills motor neurons, leading to paralysis and death 2 to 5 years from diagnosis. Currently ALS has no cure. Despite promising early-stage research, the majority of drugs in development for ALS have failed. Now researchers have uncovered a possible explanation. In a study published November 20th in the Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology, researchers show that the brain's machinery for pumping out toxins is ratcheted up in ALS ...

A lot of research has shown that poor regulation of the serotonin system, caused by certain genetic variations, can increase the risk of developing psychiatric illnesses such as autism, depression, or anxiety disorders. Furthermore, genetic variations in the components of the serotonin system can interact with stress experienced during the foetal stages and/or early childhood, which can also increase the risk of developing psychiatric problems later on.

In order to better understand serotonin's influence in the developing brain, Alexandre Dayer's team in the Psychiatry ...

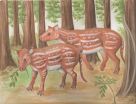

Working at the edge of a coal mine in India, a team of Johns Hopkins researchers and colleagues have filled in a major gap in science's understanding of the evolution of a group of animals that includes horses and rhinos. That group likely originated on the subcontinent when it was still an island headed swiftly for collision with Asia, the researchers report Nov. 20 in the online journal Nature Communications.

Modern horses, rhinos and tapirs belong to a biological group, or order, called Perissodactyla. Also known as "odd-toed ungulates," animals in the order have, ...

Bremerhaven/Germany, 20 November 2014. Scientists from the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) have identified a possible source of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases that were abruptly released to the atmosphere in large quantities around 14,600 years ago. According to this new interpretation, the CO2 - released during the onset of the Bølling/Allerød warm period - presumably had their origin in thawing Arctic permafrost soil and amplified the initial warming through positive feedback. The study now appears ...

The residents of Longyearbyen, the largest town on the Norwegian arctic island archipelago of Svalbard, remember it as the week that the weather gods caused trouble.

Temperatures were ridiculously warm - and reached a maximum of nearly +8 degrees C in one location at a time when mean temperatures are normally -15 degrees C. It rained in record amounts.

Snow packs became so saturated that slushy snow avalanches from the mountains surrounding Longyearbyen covered roads and took out a major pedestrian bridge.

Snowy streets and the tundra were transformed into icy, ...

MEDFORD/SOMERVILLE, Mass-- Tufts University School of Engineering researchers and collaborators from Texas A&M University have published the first research to use computational modeling to predict and identify the metabolic products of gastrointestinal (GI) tract microorganisms. Understanding these metabolic products, or metabolites, could influence how clinicians diagnose and treat GI diseases, as well as many other metabolic and neurological diseases increasingly associated with compromised GI function. The research appears in the November 20 edition of Nature Communications ...

AMHERST, Mass. -- Predicting the beginning of influenza outbreaks is notoriously difficult, and can affect prevention and control efforts. Now, just in time for flu season, biostatistician Nicholas Reich of the University of Massachusetts Amherst and colleagues at Johns Hopkins have devised a simple yet accurate method for hospitals and public health departments to determine the onset of elevated influenza activity at the community level.

Hospital epidemiologists and others responsible for public health decisions do not declare the start of flu season lightly, Reich ...