(Press-News.org) (PHILADELPHIA) - Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig's disease, is a neurodegenerative disease that primarily kills motor neurons, leading to paralysis and death 2 to 5 years from diagnosis. Currently ALS has no cure. Despite promising early-stage research, the majority of drugs in development for ALS have failed. Now researchers have uncovered a possible explanation. In a study published November 20th in the Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology, researchers show that the brain's machinery for pumping out toxins is ratcheted up in ALS patients and that this machinery also pumps out medicine designed to treat ALS, thereby decreasing the therapeutic efficacy of the drug. The work showed that when these pumps are blocked, the drug becomes more effective at slowing the progression of the disease in mouse models.

"This mechanism that normally protects the brain and the spinal cord from damage via environmental toxins, also treats the therapeutic drug as a threat and pumps that out as well" says co-senior author Piera Pasinelli, Ph.D., associate professor of neuroscience and Co-Director of the Weinberg Unit for ALS Research at Thomas Jefferson University. "Blocking the pumps, or transporter proteins, improved how well the ALS drug worked in mice."

"Drug resistance via these types of cellular drug-pumps is not new," says co-senior author Davide Trotti, Ph.D., associate professor of neuroscience and Co-Director of the Weinberg Unit for ALS research at Jefferson. "In fact, drug companies routinely check novel compounds for interactions with these transporter proteins, but they typically check in healthy animals or individuals." Because of the investigators' background in pharmacological sciences and ALS research, examining the role of drug transporter proteins made sense. But rather than look at healthy mice, the researcher looked at how these interactions changed in mouse models of the disease over time.

In research published earlier, the group showed that the function of the pumps changed as the disease progressed in mice, with the pumps becoming more active as the symptoms became more severe. "The ALS brain and spinal cord may be trying to compensate for the disease by generating more of these pumps," says Dr. Trotti. But it was unclear whether this increase would really impact treatment.

To address this question, the investigators led by Drs. Pasinelli and Trotti, tested in the mouse model of ALS the only drug approved for ALS treatment and used by patients, riluzole. Earlier work had shown that the drug loses its effectiveness in patients as the disease progresses, and overall the drug only prolongs survival of ALS patients by 3-6 months. The researchers also chose riluzole because they knew it interacted with two pumps, P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and breast-cancer resistant protein (BCRP -- first discovered for its role in drug resistance in breast cancer). These two pumps can be selectively blocked by an experimental compound called elacridar that leaves other pumps in the brain unaffected.

The team treated mice with the combination of the ALS drug (riluzole) and pump-blocker (elacridar) and showed that the combination extended the life span of mice compared with those treated only with riluzole. Importantly, the combination also alleviated some of the symptoms, improving muscle-strength and other measures in mice.

Unlike most experiments in ALS mice, in which drugs are administered before the mice exhibit symptoms of the disease in an attempt to delay onset, Pasinelli and Trotti tested their hypothesis in a model that mirrored what patients actually experience, with treatment beginning when ALS symptoms become apparent. Treating ALS mice with riluzole when symptoms appear actually provides little to no benefit alone, but together with elacridar, showed marked improvements.

"The fact that elacridar is selective may explain why we didn't see obvious side effects: other transporter proteins in the brain were still active and removing toxins. We simply plugged the ones that allowed riluzole to leak out," said Pasinelli.

The finding may also explain why ALS drugs that appear to work initially, fail as the disease progresses: as the motor neurons become more damaged, the brain creates more pumps to try to remove the damage, also removing ALS drugs with greater efficiency than before.

"The research paves a way for improving the efficacy of an already ALS approved drug, if the findings hold true in human clinical trials," says Dr. Pasinelli. "But more importantly it also sheds light on a basic pathological mechanism at play in ALS patients that might explain why so many treatments have failed, and suggests a way to re-examine these therapies together with selective pump-inhibitor."

INFORMATION:

This work was funded by DOD W81XWH-11-1-0767 ; Landenberger Foundation; National Institutes of Health RO1-NS074886; National Institutes of Health F31-NS080539; MDA Developmental Award; Farber Family Foundation.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

For more information, contact Edyta Zielinska, 215-955-5291, edyta.zielinska@jefferson.edu.

About Jefferson -- Health is all we do.

Thomas Jefferson University, Thomas Jefferson University Hospitals and Jefferson University Physicians are partners in providing the highest-quality, compassionate clinical care for patients, educating the health professionals of tomorrow, and discovering new treatments and therapies that will define the future of healthcare. Thomas Jefferson University enrolls more than 3,600 future physicians, scientists and healthcare professionals in the Sidney Kimmel Medical College (SKMC); Jefferson Schools of Health Professions, Nursing, Pharmacy, Population Health; and the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, and is home of the National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center. Jefferson University Physicians is a multi-specialty physician practice consisting of over 650 SKMC full-time faculty. Thomas Jefferson University Hospitals is the largest freestanding academic medical center in Philadelphia. Services are provided at five locations -- Thomas Jefferson University Hospital and Jefferson Hospital for Neuroscience in Center City Philadelphia; Methodist Hospital in South Philadelphia; Jefferson at the Navy Yard; and Jefferson at Voorhees in South Jersey.

Article Reference: M.R. Jablonski, et al., "Inhibiting drug efflux transporters improves efficacy of ALS

Therapeutics," Ann Clin Transl Neurol, doi: 10.1002/acn3.141, 2014.

A lot of research has shown that poor regulation of the serotonin system, caused by certain genetic variations, can increase the risk of developing psychiatric illnesses such as autism, depression, or anxiety disorders. Furthermore, genetic variations in the components of the serotonin system can interact with stress experienced during the foetal stages and/or early childhood, which can also increase the risk of developing psychiatric problems later on.

In order to better understand serotonin's influence in the developing brain, Alexandre Dayer's team in the Psychiatry ...

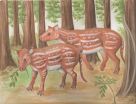

Working at the edge of a coal mine in India, a team of Johns Hopkins researchers and colleagues have filled in a major gap in science's understanding of the evolution of a group of animals that includes horses and rhinos. That group likely originated on the subcontinent when it was still an island headed swiftly for collision with Asia, the researchers report Nov. 20 in the online journal Nature Communications.

Modern horses, rhinos and tapirs belong to a biological group, or order, called Perissodactyla. Also known as "odd-toed ungulates," animals in the order have, ...

Bremerhaven/Germany, 20 November 2014. Scientists from the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) have identified a possible source of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases that were abruptly released to the atmosphere in large quantities around 14,600 years ago. According to this new interpretation, the CO2 - released during the onset of the Bølling/Allerød warm period - presumably had their origin in thawing Arctic permafrost soil and amplified the initial warming through positive feedback. The study now appears ...

The residents of Longyearbyen, the largest town on the Norwegian arctic island archipelago of Svalbard, remember it as the week that the weather gods caused trouble.

Temperatures were ridiculously warm - and reached a maximum of nearly +8 degrees C in one location at a time when mean temperatures are normally -15 degrees C. It rained in record amounts.

Snow packs became so saturated that slushy snow avalanches from the mountains surrounding Longyearbyen covered roads and took out a major pedestrian bridge.

Snowy streets and the tundra were transformed into icy, ...

MEDFORD/SOMERVILLE, Mass-- Tufts University School of Engineering researchers and collaborators from Texas A&M University have published the first research to use computational modeling to predict and identify the metabolic products of gastrointestinal (GI) tract microorganisms. Understanding these metabolic products, or metabolites, could influence how clinicians diagnose and treat GI diseases, as well as many other metabolic and neurological diseases increasingly associated with compromised GI function. The research appears in the November 20 edition of Nature Communications ...

AMHERST, Mass. -- Predicting the beginning of influenza outbreaks is notoriously difficult, and can affect prevention and control efforts. Now, just in time for flu season, biostatistician Nicholas Reich of the University of Massachusetts Amherst and colleagues at Johns Hopkins have devised a simple yet accurate method for hospitals and public health departments to determine the onset of elevated influenza activity at the community level.

Hospital epidemiologists and others responsible for public health decisions do not declare the start of flu season lightly, Reich ...

A team of scientists hope to trace the origins of gamma-ray bursts with the aid of giant space 'microphones'.

Researchers at Cardiff University are trying to work out the possible sounds scientists might expect to hear when the ultra-sensitive LIGO and Virgo detectors are switched on in 2015.

It's hoped the kilometre-scale microphones will detect gravitational waves created by black holes, and shed light on the origins of the Universe.

Researchers Dr Francesco Pannarale and Dr Frank Ohme, in Cardiff University's School of Physics and Astronomy, are exploring the potential ...

(PHILADELPHIA) - Pulmonary fibrosis has no cure. It's caused by scarring that seems to feed on itself, with the tougher, less elastic tissue replacing the ever moving and stretching lung, making it increasingly difficult for patients to breathe. Researchers debate whether the lung tissue is directly damaged, or whether immune cells initiate the scarring process - an important distinction when trying to find new ways to battle the disease. Now research shows that both processes may be important, and suggest a new direction for developing novel therapies. The work will publish ...

WASHINGTON, DC, November 17, 2014 -- A new study finds that having job authority increases symptoms of depression among women, but decreases them among men.

"Women with job authority -- the ability to hire, fire, and influence pay -- have significantly more symptoms of depression than women without this power," said Tetyana Pudrovska, an assistant professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Texas at Austin and the lead author of the study. "In contrast, men with job authority have fewer symptoms of depression than men without such power."

Titled, ...

WASHINGTON, DC, November 18, 2014 -- A new study indicates that heterosexuals have predominately egalitarian views on legal benefits for -- but not public displays of affection (PDA) by -- same-sex couples.

"We found that, for the most part, heterosexuals are equally as supportive of legal benefits for same-sex couples as they are for heterosexual couples, but are much less supportive of public displays of affection for same-sex couples than they are for heterosexuals," said Long Doan, a PhD candidate in the Department of Sociology at Indiana University and the lead author ...