(Press-News.org) Scientists have created the largest-scale map to date of direct interactions between proteins encoded by the human genome and newly predicted dozens of genes to be involved in cancer.

The new "human interactome" map describes about 14,000 direct interactions between proteins. The interactome is the network formed by proteins and other cellular components that 'stick together.' The new map is over four times larger than any previous map of its kind, containing more high-quality interactions than have come from all previous studies put together.

CIFAR Senior Fellow Frederick Roth, along with Marc Vidal (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School) co-led the international research team that wrote the forthcoming Nov. 20 paper in Cell. Roth is a senior investigator at Mount Sinai Hospital's Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute and a professor at the Donnelly Centre for Cellular and Biomolecular Research, University of Toronto. He is also a Canada Excellence Research Chair in Integrative Biology.

Using lab experiments, the scientists identified interactions and then, using computer modelling, they zoomed in on proteins that 'connect' to one or more other cancer proteins.

"We show, really for the first time, that cancer proteins are more likely to interconnect with one another than they are to connect to randomly chosen non-cancer proteins," Roth says.

"Once you see that proteins associated to the same disease are more likely to connect to each other, now you can use this network of interactions as a prediction tool to find new cancer proteins, and the genes they encode," says Roth. For example, two known cancer genes encoded two proteins that interacted with CTBP2, a protein encoded at a location tied to prostate cancer, which can spread to nearby lymph nodes. These two proteins are implicated in lymphoid tumours, suggesting that CTBP2 plays a role in the development of lymphoid tumours.

Using their predictive method, the researchers found that 60 of their predicted cancer genes fit into a known cancer pathway.

Discoveries like these are crucial for understanding how cancer and other diseases develop and ultimately, how to treat and prevent them. The vast majority of protein interactions in the human body are a mystery. Roth likens a doctor asked to treat a patient's disease to an auto mechanic.

"How can we ask someone to fix a car with an incomplete list of parts and no guidance on how the parts fit together?" he says.

Each gene can encode multiple parts, and researchers are working toward a comprehensive understanding of what all those parts are, where they are found within the cells of our bodies, and how they connect to each other. Studies in baker's yeast have mapped interactions at genome scale, but the new study is the first to approach this scale in humans.

The study also reveals that the network of protein interactions in humans covers a much broader range of genes than some past research has suggested. Studies often focus on 'popular' proteins that are already known to be tied to disease or to be interesting for other reasons, which has created a bias in our understanding of interactions, Roth says.

"One major conclusion of the paper is that when you look systematically for interactions, you find them everywhere," he says.

Roth says the research is central to the goals of CIFAR's Genetic Networks program, particularly building the map of how an organism's genotype, the set of its genes, connects to an organism's phenotype, its characteristics that include appearance and predisposition to disease. Knowledge of interactions is likely to inform worldwide efforts to sequence and interpret cancer genomes.

INFORMATION:

About CIFAR

CIFAR creates knowledge that will transform our world. The Institute brings together outstanding researchers to work in global networks that address some of the most important questions our world faces today. Our networks help support the growth of research leaders and are catalysts for change in business, government and society.

Established in 1982, CIFAR is a Canadian-based, global organization, comprised of nearly 350 fellows, scholars and advisors from more than 100 institutions in 16 countries. CIFAR partners with the Government of Canada, provincial governments, individuals, foundations, corporations and research institutions to extend our impact in the world.

About the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute

The Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute, located at Mount Sinai Hospital, is one of the leading biomedical research facilities in the world. Created in 1985, the institute is profoundly advancing the understanding of human biology in health and disease. Many of the breakthroughs that began as fundamental research have already resulted in new and better ways to prevent, diagnose and treat common illnesses ― bringing a healthier future to Canadians.

Contacts:

Lindsay Jolivet

Writer & Media Relations Specialist

Canadian Institute for Advanced Research

lindsay.jolivet@cifar.ca

(416) 971-4876

Sandeep Dhaliwal

Communications Specialist

Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute, Mount Sinai Hospital

dhaliwal@lunenfeld.ca

416-586-4800 ext. 2046

PHILADELPHIA - Human existence is basically circadian. Most of us wake in the morning, sleep in the evening, and eat in between. Body temperature, metabolism, and hormone levels all fluctuate throughout the day, and it is increasingly clear that disruption of those cycles can lead to metabolic disease.

Underlying these circadian rhythms is a molecular clock built of DNA-binding proteins called transcription factors. These proteins control the oscillation of circadian genes, serving as the wheels and springs of the clock itself. Yet not all circadian cycles peak at the ...

Harvard Stem Cell Institute scientists at Brigham and Women's Hospital have found the cellular origin of the tissue scarring caused by organ damage associated with diabetes, lung disease, high blood pressure, kidney disease, and other conditions. The buildup of scar tissue is known as fibrosis.

Fibrosis has a number of consequences, including inflammation, and reduced blood and oxygen delivery to the organ. In the long term, the scar tissue can lead to organ failure and eventually death. It is estimated that fibrosis contributes to 45 percent of all deaths in the developed ...

Liver cancer is one of the most frequent cancers in the world, and with the worst prognosis; according to the World Health Organisation (WHO), in 2012, 745,000 deaths were registered worldwide due to this cause, a figure only surpassed by lung cancer. The most aggressive and frequent form of liver cancer is hepato-cellular carcinoma (HCC); little is known about it and there are relatively few treatment options.

Researchers from the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO), have produced the first mouse model that faithfully reproduces the steps of human HCC development, ...

Mouse cells and tissues created through nuclear transfer can be rejected by the body because of a previously unknown immune response to the cell's mitochondria, according to a study in mice by researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine and colleagues in Germany, England and at MIT.

The findings reveal a likely, but surmountable, hurdle if such therapies are ever used in humans, the researchers said.

Stem cell therapies hold vast potential for repairing organs and treating disease. The greatest hope rests on the potential of pluripotent stem cells, which ...

A recently discovered protein complex known as STING plays a crucial role in detecting the presence of tumor cells and promoting an aggressive anti-tumor response by the body's innate immune system, according to two separate studies published in the Nov. 20 issue of the journal Immunity.

The studies, both from University of Chicago-based research teams, have major implications for the growing field of cancer immunotherapy. The findings show that when activated, the STING pathway triggers a natural immune response against the tumor. This includes production of chemical ...

Say you ignored one of those "this website is not trusted" warnings and it led to your computer being hacked. How would you react? Would you:

A. Quickly shut down your computer?

B. Yank out the cables?

C. Scream in cyber terror?

For a group of college students participating in a research experiment, all of the above were true. These gut reactions (and more) happened when a trio of Brigham Young University researchers simulated hacking into study participants' personal laptops.

"A lot of them freaked out--you could hear them audibly make noises from our observation ...

November 20, 2014, Chicago, IL - A team of researchers led by Ludwig Chicago's Yang-Xin Fu and Ralph Weichselbaum has uncovered the primary signaling mechanisms and cellular interactions that drive immune responses against tumors treated with radiotherapy. Published in the current issue of Immunity, their study suggests novel strategies for boosting the effectiveness of radiotherapy, and for combining it with therapies that harness the immune system to treat cancer.

"Much of the conversation about the mechanisms by which radiation kills cancer cells has historically focused ...

BOSTON -- Epithelial ovarian cancer is the most lethal cancer of the female reproductive organs, with more than 200,000 new cases and more than 125,000 deaths each year worldwide. Because symptoms tend to be vague, 80 percent of these cancers are not recognized until the disease has advanced and spread to other parts of the body. The standard treatment for advanced ovarian cancer includes high-dose chemotherapy, which often results in debilitating side effects and for which the five-year survival rate is only 35 percent.

Now new research in an animal model finds that ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Researchers from Oregon State University and other institutions have developed a new biomarker called "SDMA" that can provide earlier identification of chronic kidney disease in cats, which is one of the leading causes of their death.

A new test based on this biomarker, when commercialized, should help pet owners and their veterinarians watch for this problem through periodic checkups, and treat it with diet or other therapies to help add months or years to their pet's life.

Special diets have been shown to slow the progression of this disease once ...

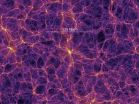

RIVERSIDE, Calif. - How do galaxies like our Milky Way form, and just how do they evolve? Are galaxies affected by their surrounding environment? An international team of researchers, led by astronomers at the University of California, Riverside, proposes some answers.

The researchers highlight the role of the "cosmic web" - a large-scale web-like structure comprised of galaxies - on the evolution of galaxies that took place in the distant universe, a few billion years after the Big Bang. In their paper, published Nov. 20 in the Astrophysical Journal, they present observations ...