(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA, CA - November 20, 2014 - Scientists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have discovered how one gene is essential to hearing, uncovering a cause of deafness and suggesting new avenues for therapies.

The new study, published November 20 in the journal Neuron, shows how mutations in a gene called Tmie can cause deafness from birth. Underlining the critical nature of their findings, researchers were able to reintroduce the gene in mice and restore the process underpinning hearing.

"This raises hopes that we could, in principle, use gene-therapy approaches to restore function in hair cells and thus develop new treatment options for hearing loss," said Professor Ulrich Müller, senior author of the new study, chair of the Department of Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience and director of the Dorris Neuroscience Center at TSRI.

The Gene Responsible

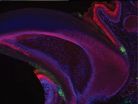

The ear is a complex machine that converts mechanical sound waves into electric signals for the brain to process. When a sound wave enters the ear, the uneven ends (stereocilia) of the inner ear's hair cells are pushed back, like blades of grass bent by a heavy wind. The movement causes tension in the strings of proteins (tip links) connecting the stereocilia, which sends a signal to the brain through ion channels that run through the tips of the hair cell bundles.

This process of converting mechanical force into electrical activity, called mechanotransduction, still poses many mysteries. In this case, researchers were in the dark about how signals were passed along the tip links to the ion channels, which shape electrical signals.

To track down this unknown component, researchers in the new study built a library of thousands of genes with the potential to affect mechanotransduction.

The team spent six months screening the genes to see if the proteins the genes produced interacted with tip link proteins. Eventually, the team found a gene, Tmie, whose protein, TMIE, interacts with tip link proteins and connects the tip links to a piece of machinery near the ion channel.

A Path to New Treatments

This discovery answers a long-standing question in neuroscience. Scientists have long known that mutations in the Tmie gene could cause deafness--but they weren't sure how.

Once they found that TMIE plays a role bridging the tip links and ion channels, the researchers bred a population of "knock-out mice" that lacked the gene. They examined the hair cells of the mice with electrophysiological techniques and found that without TMIE, no electrical signal could be evoked in hair cells after stimulation.

"The mechanotransduction current is gone; the mouse is totally deaf," explained Bo Zhao, a research associate in the Müller lab and first author of the new paper.

In a second experiment, the researchers reintroduced Tmie to mice that had been deaf since birth and found the electrical signals were restored.

Müller said the next challenge is to find out how the individual components of the complex mechanotransduction system form in hair cells. "We would also like to understand the biophysical principles by which these proteins convert mechanical signals into electrical signals," he said.

INFORMATION:

In addition to Müller and Zhao, the authors of the paper "TMIE is an Essential Component of the Mechanotransduction Machinery of Cochlear Hair Cells" were Zizhen Wu, Linxuan Yan, Wei Xiong and Sarah Harkins-Perry of TSRI; and Nicolas Grillet of Stanford University. For more information, see http://www.cell.com/neuron/abstract/S0896-6273(14)00961-1

Funding for the research was provided by the National Institutes of Health (UM DC005965 and DC007704), the Dorris Neuroscience Center, the Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology and the Bundy Foundation.

About The Scripps Research Institute

The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) is one of the world's largest independent, not-for-profit organizations focusing on research in the biomedical sciences. TSRI is internationally recognized for its contributions to science and health, including its role in laying the foundation for new treatments for cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, hemophilia, and other diseases. An institution that evolved from the Scripps Metabolic Clinic founded by philanthropist Ellen Browning Scripps in 1924, the institute now employs about 3,000 people on its campuses in La Jolla, CA, and Jupiter, FL, where its renowned scientists--including two Nobel laureates--work toward their next discoveries. The institute's graduate program, which awards PhD degrees in biology and chemistry, ranks among the top ten of its kind in the nation. For more information, see http://www.scripps.edu.

There are plenty of body parts that don't grow back when you lose them. Nails are an exception, and a new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) reveals some of the reasons why.

A team of USC Stem Cell researchers led by principal investigator Krzysztof Kobielak and co-first authors Yvonne Leung and Eve Kandyba has identified a new population of nail stem cells, which have the ability to either self-renew or undergo specialization or differentiation into multiple tissues.

To find these elusive stem cells, the team used a sophisticated ...

Stress activates the immune system

The team focused mainly on a certain type of phagocytes, namely microglia. Under normal circumstances, they repair synapses between nerves cells in the brain and stimulate their growth. Once activated, however, microglia may damage nerve cells and trigger inflammation processes. The studies carried out in Bochum have shown that the more frequently microglia get triggered due to stress, the more they are inclined to remain in the destructive mode - a risk factor for mental diseases such as schizophrenia.

Susceptibility for stress effects ...

A protein kinase or enzyme known as PKM2 has proven to control cell division, potentially providing a molecular basis for tumor diagnosis and treatment.

A study, led by Zhimin Lu, M.D., Ph.D., professor of neuro-oncology at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, showcased the non-metabolic abilities of PKM2 (pyruvate kinase M2) in promoting tumor cell proliferation when cells produce more of the enzyme.

The study results were published in today's issue of Nature Communications.

Dr. Lu's group previously demonstrated that PKM2 controls gene expression ...

Immunity is a thankless job. Though the army of cells known as the immune system continuously keeps us safe from a barrage of viruses, bacteria and even precancerous cells, we mainly notice it when something goes wrong: "Why did I get the flu this year even though I got vaccinated?" "Why does innocent pollen turn me into a red-eyed, sniffling mess?"

A new study from Johns Hopkins takes a big step toward answering this and other questions about immunity, shedding light on how the body recognizes enemies on the molecular level -- and how that process can go wrong. The results ...

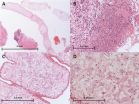

A genome of a rare species of tapeworm found living inside a patient's brain has been sequenced for the first time, in research published in the open access journal Genome Biology. The study provides insights into potential drug targets within the genome for future treatments.

Tapeworms are parasites that are most commonly found living in the gut, causing symptoms such as weakness, weight loss and abdominal pain. However, the larvae of some species of tapeworm are able to travel further afield to areas such as the eyes, the brain and spinal cord.

A 50-year-old man ...

For the first time, the genome of a rarely seen tapeworm has been sequenced. The genetic information of this invasive parasite, which lived for four years in a UK resident's brain, offers new opportunities to diagnose and treat this invasive parasite.

The tapeworm, Spirometra erinaceieuropaei, has been reported only 300 times worldwide since 1953 and has never been seen before in the UK. The worm causes sparganosis: inflammation of the body's tissues in response to the parasite. When this occurs in the brain, it can cause seizures, memory loss and headaches. The worm's ...

Current efforts to prevent violence against women and girls are inadequate, according to a new Series published in The Lancet. Estimates suggest that globally, 1 in 3 women has experienced either physical or sexual violence from their partner, and that 7% of women will experience sexual assault by a non-partner at some point in their lives.

Yet, despite increased global attention to violence perpetrated against women and girls, and recent advances in knowledge about how to tackle these abuses (Paper 1, Paper 3), levels of violence against women - including intimate ...

WASHINGTON--Levels of violence against women and girls--such as female genital mutilation, trafficking, forced marriage and intimate partner violence--remain high across the world despite the global attention the issue has received. The focus needs to shift to preventing violence, rather than just dealing with the consequences, according to a new series on violence against women and girls published Friday in The Lancet.

Mary Ellsberg, director of the George Washington University's Global Women's Institute (GWI), co-authored one of the five papers published in the special ...

Barcelona, Spain: In a second presentation looking at new ways of treating non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) that has both the EGFR and T790M mutations, researchers will tell the 26th EORTC-NCI-AACR [1] Symposium on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics in Barcelona, Spain, that an oral drug called ASP8273 has caused tumour shrinkage in patients in a phase I clinical trial in Japan.

Mutations of the epidermal growth factor (EGFR) occur in about 30-35% of Asian patients with NSCLC (and in 10-15% of Caucasian patients). EGFR inhibitors called tyrosine kinase inhibitors ...

Highlights

Living organ donors who later need kidney transplants have much shorter waiting times, and they receive higher quality kidneys compared with similar people on the waiting list who were not organ donors.

In 2010, a total of 16,900 kidney transplants took place in the U.S. Of those, only 6,278 were from living donors.

Washington, DC (November 20, 2014) -- Prior organ donors who later need a kidney transplant experience brief waiting times and receive excellent quality kidneys, according to a study appearing in an upcoming issue of the Journal of the American ...