Circumstances are right for weed invasion to escalate, researchers say

Don't plant invasive species in search of green pastures, researchers warn

2014-11-25

(Press-News.org) Few agribusinesses or governments regulate the types of plants that farmers use in their pastures to feed their livestock, according to an international team of researchers that includes one plant scientist from Virginia Tech.

The problem is most of these so-called pasture plants are invasive weeds.

In a Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences study this month, the scientists recommended tighter regulations, including a fee for damage to surrounding areas, evaluation of weed risk to the environment, a list of prohibited species based on this risk, and closer monitoring and control of natural area damage.

The findings were also highlighted Nov. 12 in Nature.

The research team -- led by scientists at the Australian National University -- surveyed agribusinesses in eight countries on six different continents to see what species are planted in pastures, what traits are selected for, and what measures are taken to guard against invasion.

In response to human population boom and increased global food demand, some farmers resort to planting aggressive, fast-growing species in order to increase their herd size without breaking the bank.

This extensive growth allows for greater cattle forage, but has a long global history of escaping the paddocks and invading natural areas, where they squelch out biodiversity, suck up available water resources, enhance fire cycles, disrupt the behavior patterns of pollinators, and alter nutrient and trophic levels.

In turn, about $34 billion per year is spent annually in the United States on invasive weed management, said Jacob Barney, an assistant professor of plant pathology, physiology, and weed science in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Fralin Life Science Institute affiliate, and third author of the study.

"Meat consumption is increasing globally, which will increase animal production, and thus increase demand for forages improved for forage quality, productivity, and tolerance of poor growing conditions -- all traits that may facilitate invasion into the natural ecosystem, making the invasion problem worse," said Barney, who is also a core faculty member in Virginia Tech's Interfaces of Global Change program.

"The weed problem faced by the USA and other countries is already enormous," said Don Driscoll, an associate professor at the Australian National University and lead author. "It makes sense to have new regulations that discourage agribusinesses from releasing more aggressive varieties of these existing weeds. A polluter-pays system applied across the livestock and feed industry would be an important disincentive that could help to solve this escalating weed problem."

INFORMATION:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2014-11-25

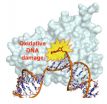

Using a new imaging technique, National Institutes of Health researchers have found that the biological machinery that builds DNA can insert molecules into the DNA strand that are damaged as a result of environmental exposures. These damaged molecules trigger cell death that produces some human diseases, according to the researchers. The work, appearing online Nov. 17 in the journal Nature, provides a possible explanation for how one type of DNA damage may lead to cancer, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular and lung disease, and Alzheimer's disease.

Time-lapse crystallography ...

2014-11-25

PHILADELPHIA (Nov. 25, 2014) - As the linked epidemics of obesity and diabetes continue to escalate, a staggering one in five U.S. adults is projected to have diabetes by 2050.

Ground zero for identifying ways to slow and stop that rise is Philadelphia, which has the highest diabetes rate among the nation's largest cities. For public health researchers at Drexel University, it is also a prime location to learn how neighborhood and community-level factors -- not just individual factors like diet, exercise and education-- influence people's risk.

A new Drexel study published ...

2014-11-25

PITTSBURGH, Nov. 24, 2014 -Barriers to the sharing of public health data hamper decision-making efforts on local, national and global levels, and stymie attempts to contain emerging global health threats, an international team led by the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health announced today.

The analysis, published in the journal BMC Public Health and funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), classifies and examines the barriers in order to open a focused international dialogue on solutions.

"Data on ...

2014-11-25

The proper regulation of body size is of fundamental importance, but the mechanisms that stop growth are still unclear. In a study now published in the scientific journal eLife*, a research group from Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência (IGC), led by Christen Mirth, shed new light on how animals regulate body size. The researchers uncovered important clues about the molecular mechanisms triggered by environmental conditions that ultimately affect final body size. They show that the timing of synthesis of a steroid hormone called ecdysone is sensitive to nutrition in the ...

2014-11-25

People's views on income inequality and wealth distribution may have little to do with how much money they have in the bank and a lot to do with how wealthy they feel in comparison to their friends and neighbors, according to new findings published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

"Our research shows that subjective feelings of wealth or poverty motivate people's attitudes toward redistribution, quite independently of objective self-interest," says psychological scientist and study co-author Keith Payne of the University ...

2014-11-25

WASHINGTON, Nov. 25, 2014 -- Your beer may attract annoying fruit flies, but listen up before you give them a swat. Researchers found the yeast cells in beer are producing odor compounds -- acetate esters -- that lure flies and that could lead to the best beer you haven't even tasted yet. This week's Speaking of Chemistry explains why. Check it out at http://youtu.be/HQNlGuZvCvA.

Speaking of Chemistry is a production of Chemical & Engineering News, a weekly magazine of the American Chemical Society. The program features fascinating, weird and otherwise interesting chemistry ...

2014-11-25

Bitcoin is the new money: minted and exchanged on the Internet. Faster and cheaper than a bank, the service is attracting attention from all over the world. But a big question remains: are the transactions really anonymous? Several research groups worldwide have shown that it is possible to find out which transactions belong together, even if the client uses different pseudonyms. However it was not clear if it is also possible to reveal the IP address behind each transaction. This has changed: researchers at the University of Luxembourg have now demonstrated how this is ...

2014-11-25

The study at Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, was based on the Swedish National Epilepsy Surgery Register, which includes all cases since 1990. The researchers reviewed data for the 865 patients who were operated on at Sweden's six epilepsy surgery clinics from 1996 to 2010.

The purpose of surgery is to enable a person with severe epilepsy to be free of seizures or to reduce their frequency to the point that (s)he can enjoy better quality of life.

Downward trend

Only 3% (25) of the patients suffered lasting complications. A comparison with a previous ...

2014-11-25

Researchers at KU Leuven's Centre for Surface Chemistry and Catalysis have successfully converted sawdust into building blocks for gasoline. Using a new chemical process, they were able to convert the cellulose in sawdust into hydrocarbon chains. These hydrocarbons can be used as an additive in gasoline, or as a component in plastics. The researchers reported their findings in the journal Energy & Environmental Science.

Cellulose is the main substance in plant matter and is present in all non-edible plant parts of wood, straw, grass, cotton and old paper. "At the molecular ...

2014-11-25

Results presented November 19 by University of Colorado Cancer Center investigator Daniel Pollyea, MD, MS, at the 26th European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Symposium in Barcelona show "extremely promising" early phase 1 clinical trial results for the investigational drug AG-120 against the subset of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) harboring mutations in the gene IDH1. The finding builds on phase 1 results of a related drug, AG-221, against IDH2 mutations, presented at the most recent meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research. ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Circumstances are right for weed invasion to escalate, researchers say

Don't plant invasive species in search of green pastures, researchers warn