(Press-News.org) HOUSTON - (Nov. 25, 2014) - An international collaboration of scientists including Baylor College of Medicine has completed the first genome sequence of a myriapod, Strigamia maritima - a member of a group venomous centipedes that care for their eggs - and uncovered new clues about their biological evolution and unique absence of vision and circadian rhythm.

Over 100 researchers from 12 countries completed the project. They published their work online today in the journal PLOS Biology.

"This is the first myriapod and the last of the four classes of arthropods to have its genome sequenced," said Dr. Stephen Richards, assistant professor in the Human Genome Sequencing Center at Baylor, where the sequencing of the project was completed, and the corresponding author on the report. "Arthropods are particularly interesting for scientific study because they diverged into more species than any other animal group as they adapted in many ways to conquer the planet. The genome of the myriapod in comparison with previously completed genomes of the other arthropod classes gives us an important view of the evolutionary changes of these exciting species."

Dr. Ariel Chipman, of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel, Dr. David Ferrier, of The University of St. Andrews in the United Kingdom, and Dr. Michael Akam of the University of Cambridge in the UK, together with Richards served as key players in the collaboration.

"The arthropods have been around for over 500 million years and the relationship between the different groups and early evolution of the species is not really well understood," said Chipman, associate professor at the Hebrew University. "We have good sampling of insects but this is the first time a centipede, one of the more simple arthropods - simple in terms of body plan, no wings, simple repetitive segments, etc. -- has been sequenced. This is a more conservative genome, not necessarily ancient or primitive, but one that has retained ancient features more than other groups."

"From fossil evidence, we know the myriapods are one of three independent arthropod invasions of the land (from the sea), in addition to the insects and spiders. So they had to find a way to smell chemicals in air, rather then taste them in water. The team identified large gene expansions of the gustatory (taste) receptors suspected to fill the olfactory role that olfactory (smell) receptors play in insects," Richards said. "This is a nice example of parallel evolution where different group of genes expanded, providing a different solution to the same problem."

One interesting finding revolved around this particular centipede group losing its eyes at least 200 million years ago.

No genes related solely to vision were found in the genome, and interestingly, genes related to the circadian clock were also missing. The circadian clock regulates sleep and causes jetlag and also relies on light input to synchronize with day and night.

"This teaches us about how evolution works and how things change, how things can be conserved and others lost," said Chipman. "In general, this just gives us a better understanding of biology and how it works over long periods of time."

"Strigamia (centipedes) live underground and have no eyes, so it is not surprising that many of the genes for light receptors are missing, but they behave as if they are hiding from the light. They must have some alternative way of detecting when they are exposed," says Akam, head of zoology at Cambridge and one of the lead researchers.

"It's curious, too, that this creature appears to have no body clock - or if it does, it must use a system very different to other animals."

The centipede's genome sequence is of more than just scientific interest, said Akam.

"Some of its genes may be of direct use. All centipedes inject venom to paralyse their prey," he explains. "Components of venom often make powerful drugs, and the centipede genome will help researchers find these venom genes."

INFORMATION:

The majority of funding for this work was provided by a grant from the National Human Genome Research Institute to Baylor College of Medicine's Human Genome Sequencing Center.

Glenna Picton

713-798-4710

picton@bcm.edu

http://www.bcm.edu/news

The arthropods are one of Earth's real success stories, with more species of arthropod than in any other animal phylum, but our knowledge of arthropod genomes has been heavily skewed towards the insects. Recent work has furnished us with the genome sequences of an arachnid and a crustacean, but the myriapods (centipedes and millipedes) have remained the one class of arthropods whose genomes are still in the dark.

An international team of scientists (over 100 from 15 countries) with Stephen Richards (Baylor College of Medicine) as senior author has now sequenced the genome ...

Centipedes, those many-legged creatures that startle us in our homes and gardens, have been genetically sequenced for the first time. In a new study in the journal PLoS Biology, an international team of over 100 scientists today reveals how this humble arthropod's DNA gave them new insight into how life developed on our planet.

Centipedes are members of the arthropods, a group with numerous species including insects, spiders and other animals. Until now, the only class of arthropods not represented by a sequenced genome was the myriapods, which include centipedes and ...

Learning-related brain activity in Parkinson's patients improves as much in response to a placebo treatment as to real medication, according to a new study by researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder and Columbia University.

Past research has shown that while Parkinson's disease is a neurological reality, the brain systems involved may also be affected by a patient's expectations about treatment. The new study, published in the journal Nature Neuroscience, explains how the placebo treatment -- when patients believe they have received medication when they have ...

Endangered Snake River sockeye salmon are regaining the fitness of their wild ancestors, with naturally spawned juvenile sockeye migrating to the ocean and returning as adults at a much higher rate than others released from hatcheries, according to a newly published analysis. The analysis indicates that the program to save the species has succeeded and is now shifting to rebuilding populations in the wild.

Biologists believe the increased return rate of sockeye spawned naturally by hatchery-produced parents is high enough for the species to eventually sustain itself in ...

MAYWOOD, Il. - An award-winning study by a Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine researcher has documented how homeless, mentally ill women in India face a vicious cycle:

During psychotic episodes, they wander away from home, sometimes for long distances, and wind up in homeless shelters. They then are returned to their families before undergoing sufficient psychosocial rehabilitation to deal with their illness. Consequently, they suffer mental illness relapses and wind up homeless again.

"The study illustrates how there must be a balance between reintegrating ...

While the turkey you eat on Thursday will bring your stomach happiness and could probably kick-start an afternoon nap, it may also save your life one day.

That's because the biological machinery needed to produce a potentially life-saving antibiotic is found in turkeys. Looks like there is one more reason to be grateful this Thanksgiving.

"Our research group is certainly thankful for turkeys," said BYU microbiologist Joel Griffitts, whose team is exploring how the turkey-born antibiotic comes to be. "The good bacteria we're studying has been keeping turkey farms healthy ...

How is it that vultures can live on a diet of carrion that would at least lead to severe food-poisoning, and more likely kill most other animals? This is the key question behind a recent collaboration between a team of international researchers from Denmark's Centre for GeoGenetics and Biological Institute at the University of Copenhagen, Aarhus University, the Technical University of Denmark, Copenhagen Zoo and the Smithsonian Institution in the USA. An "acidic" answer to this question is now published in the scientific journal Nature Communications.

When vultures eat ...

Who knew Blu-ray discs were so useful? Already one of the best ways to store high-definition movies and television shows because of their high-density data storage, Blu-ray discs also improve the performance of solar cells -- suggesting a second use for unwanted discs -- according to new research from Northwestern University.

An interdisciplinary research team has discovered that the pattern of information written on a Blu-ray disc -- and it doesn't matter if it's Jackie Chan's "Supercop" or the cartoon "Family Guy" -- works very well for improving light absorption across ...

New York, NY, November 25, 2014 - Testosterone (T) therapy is routinely used in men with hypogonadism, a condition in which diminished function of the gonads occurs. Although there is no evidence that T therapy increases the risk of prostate cancer (PCa), there are still concerns and a paucity of long-term data. In a new study in The Journal of Urology®, investigators examined three parallel, prospective, ongoing, cumulative registry studies of over 1,000 men. Their analysis showed that long-term T therapy in hypogonadal men is safe and does not increase the risk of ...

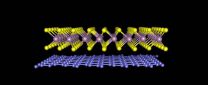

LAWRENCE -- Physicists at the University of Kansas have fabricated an innovative substance from two different atomic sheets that interlock much like Lego toy bricks. The researchers said the new material -- made of a layer of graphene and a layer of tungsten disulfide -- could be used in solar cells and flexible electronics. Their findings are published today by Nature Communications.

Hsin-Ying Chiu, assistant professor of physics and astronomy, and graduate student Matt Bellus fabricated the new material using "layer-by-layer assembly" as a versatile bottom-up nanofabrication ...