INFORMATION:

Ms Marchingo is a PhD student enrolled through The University of Melbourne's Department of Medical Biology. The research was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council, the Human Frontier Science Program, the Australian Research Council, Science Foundation Ireland, the Australian Postgraduate Award scheme, the Edith Moffatt Scholarship Fund, and the Victorian Government.

A numbers game: Math helps to predict how the body fights disease

2014-11-27

(Press-News.org) Walter and Eliza Hall Institute researchers have defined for the first time how the size of the immune response is controlled, using mathematical models to predict how powerfully immune cells respond to infection and disease.

The finding, published today in the journal Science, has implications for our understanding of how harmful or beneficial immune responses can be manipulated for better health.

The research team used mathematics and computer modeling to understand how complex signaling impacts the size of the response by key infection-fighting immune cells called T cells. The team included Ms Julia Marchingo, Dr Andrey Kan, Dr Susanne Heinzel and Professor Phil Hodgkin from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, and Professor Ken Duffy from the National University of Ireland, Maynooth.

T cells are important for launching specific immune responses against invading microbes, as well as eliminating some cancer cells. Errors in the control of T cells can lead to harmful 'autoimmune' responses that attack the body's own tissues, the underlying cause of diseases including type 1 diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis.

The team combined laboratory data with mathematical models to clarify how different external signals impact on T cell proliferation, Ms Marchingo said. "The more times T cells divide, the more powerfully they can fight their target," she said. "For example, if T cells are responding to a vaccine, more division can produce a better protective immune response.

"The outcome of our research is that, for the first time, we are able to predict the size of an immune response, such as the response to flu virus, based on the sum of the signals received by the flu-responsive T cells."

Dr Heinzel, who jointly led the research with Professor Hodgkin, said the new models provided particular insights into how immune responses might be manipulated to improve health. "Therapies that harness the immune system to attack cancerous cells have begun to show great promise for treating cancer," she said. "Our research provides clarity about how these anti-cancer immune responses could be enhanced to develop new, and improve existing, cancer treatments."

Professor Hodgkin said the research also showed how 'errors' in the developing immune response contribute to autoimmune disease. "Many of these diseases are not caused by a single change in our body, but by complex, very subtle changes in many factors affecting T cells," he said. "In the case of harmful T cells responses against our own body tissues, this model clarifies that many small changes in the signals delivered to T cells can have a cumulative effect, enough to trigger a harmful immune response.

"In the long run this may enhance efforts to predict a person's risk of autoimmune disease, and improve how these conditions are treated," Professor Hodgkin said.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Education is key to climate adaptation

2014-11-27

Given that some climate change is already unavoidable--as just confirmed by the new IPCC report--investing in empowerment through universal education should be an essential element in climate change adaptation efforts, which so far focus mostly in engineering projects, according to a new study from the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) published in the journal Science.

The article draws upon extensive analysis of natural disaster data for 167 countries over the past four decades as well as a number of studies carried out in individual countries ...

Notre Dame biologist leads sequencing of the genomes of malaria-carrying mosquitoes

2014-11-27

Nora Besansky, O'Hara Professor of Biological Sciences at the University of Notre Dame and a member of the University's Eck Institute for Global Health, has led an international team of scientists in sequencing the genomes of 16 Anopheles mosquito species from around the world.

Anopheles mosquitoes are responsible for transmitting human malaria parasites that cause an estimated 200 million cases and more than 600 thousand deaths each year. However, of the almost 500 different Anopheles species, only a few dozen can carry the parasite and only a handful of species are responsible ...

Mosquitoes and malaria: Scientists pinpoint how biting cousins have grown apart

2014-11-27

Certain species of mosquitoes are genetically better at transmitting malaria than even some of their close cousins, according to a multi-institutional team of researchers including Virginia Tech scientists.

Of about 450 different species of mosquitoes in the Anopheles genus, only about 60 can transmit the Plasmodium malaria parasite that is harmful to people. The team chose 16 mosquito species that are currently found in Africa, Asia, Europe, and Latin America, but evolved from the same ancestor approximately 100 million years ago.

Today, the 16 species have varying ...

Social media data contain pitfalls for understanding human behavior

2014-11-27

A growing number of academic researchers are mining social media data to learn about both online and offline human behavior. In recent years, studies have claimed the ability to predict everything from summer blockbusters to fluctuations in the stock market.

But mounting evidence of flaws in many of these studies points to a need for researchers to be wary of serious pitfalls that arise when working with huge social media data sets, according to computer scientists at McGill University in Montreal and Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.

Such erroneous results ...

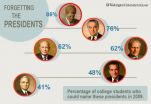

Most American presidents destined to fade from nation's memory, study suggests

2014-11-27

American presidents spend their time in office trying to carve out a prominent place in the nation's collective memory, but most are destined to be forgotten within 50-to-100 years of their serving as president, suggests a study on presidential name recall released today by the journal Science.

"By the year 2060, Americans will probably remember as much about the 39th and 40th presidents, Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, as they now remember about our 13th president, Millard Fillmore," predicts study co-author Henry L. Roediger III, PhD, a human memory expert at Washington ...

Bitter food but good medicine from cucumber genetics

2014-11-27

High-tech genomics and traditional Chinese medicine come together as researchers identify the genes responsible for the intense bitter taste of wild cucumbers. Taming this bitterness made cucumber, pumpkin and their relatives into popular foods, but the same compounds also have potential to treat cancer and diabetes.

"You don't eat wild cucumber, unless you want to use it as a purgative," said William Lucas, professor of plant biology at the University of California, Davis and coauthor on the paper to be published Nov. 28 in the journal Science.

That bitter flavor in ...

Another human footprint in the ocean

2014-11-27

Human-induced changes to Earth's carbon cycle - for example, rising atmospheric carbon dioxide and ocean acidification - have been observed for decades. However, a study published this week in Science showed human activities, in particular industrial and agricultural processes, have also had significant impacts on the upper ocean nitrogen cycle.

The rate of deposition of reactive nitrogen (i.e., nitrogen oxides from fossil fuel burning and ammonia compounds from fertilizer use) from the atmosphere to the open ocean has more than doubled globally over the last 100 years. ...

Single-atom gold catalysts may offer path to low-cost production of fuel and chemicals

2014-11-27

MEDFORD/SOMERVILLE, Mass.(November 27, 2014, 2 PM) -- New catalysts designed and investigated by Tufts University School of Engineering researchers and collaborators from other university and national laboratories have the potential to greatly reduce processing costs in future fuels, such as hydrogen. The catalysts are composed of a unique structure of single gold atoms bound by oxygen to several sodium or potassium atoms and supported on non-reactive silica materials. They demonstrate comparable activity and stability with catalysts comprising precious metal nanoparticles ...

Fragile X study offers hope of new autism treatment

2014-11-27

People affected by a common inherited form of autism could be helped by a drug that is being tested as a treatment for cancer.

Researchers who have identified a chemical pathway that goes awry in the brains of Fragile X patients say the drug could reverse their behavioural symptoms.

The scientists have found that a known naturally occurring chemical called cercosporamide can block the pathway and improve sociability in mice with the condition.

The team at the University of Edinburgh and McGill University in Canada identified a key molecule - eIF4E - that drives excess ...

OU professor and team discover first evidence of milk consumption in ancient dental plaque

2014-11-27

Led by a University of Oklahoma professor, an international team of researchers has discovered the first evidence of milk consumption in the ancient dental calculus--a mineralized dental plaque--of humans in Europe and western Asia. The team found direct evidence of milk consumption preserved in human dental plaque from the Bronze Age to the present day.

"The study has far-reaching implications for understanding the relationship between human diet and evolution," said Christina Warinner, professor in the OU Department of Anthropology. "Dairy products are a very recent, ...