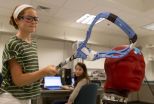

Two of the most common and terrifying symptoms of this severe anxiety are a sense of shortness of breath and feelings of suffocation. Studies have shown that breathing air that has increased levels of carbon dioxide can trigger panic attacks in most people with panic disorder as opposed to people without the disorder.

The mechanisms through which carbon dioxide inhalation produces anxiety are also not well understood. One theory is that panic disorder involves an overly sensitive "suffocation alarm system" in the brain that evolved to protect us from suffocating, and that panic attacks result when this alarm gets triggered by signals of impending suffocation like rising carbon dioxide levels.

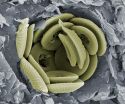

Previous research in mice showed that a protein called ASIC1a acts, indirectly, as a carbon dioxide sensor in the amygdala, a region in the brain key to the perception of danger and fear, and that the ASIC1a gene regulates carbon-dioxide induced anxiety.

A collaborative group of international researchers has now studied the human version of the ASIC1a gene, ACCN2, and report their findings in the current issue of Biological Psychiatry.

The researchers genotyped and compared variants in ACCN2 in 414 individuals with panic disorder and 846 healthy controls. In a separate group of healthy individuals, they used genotyping and neuroimaging to examine potential genetic associations with amygdala volume in 1048 subjects and amygdala function in a subset of more than 100 subjects.

"We found that different forms or variants of the human ASIC1a gene appear to be associated with panic disorder. The effect was stronger in those whose panic attacks have prominent respiratory symptoms, including shortness of breath and feelings of suffocation," explained Dr. Jordan W. Smoller, co-senior author and Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital.

"Next, we found that the panic-associated variants in the ASIC1a gene are also associated with both the size of the amygdala and a greater amygdala response to emotional threat, even in people without panic disorder."

Dr. Bruce M. Cohen, co-senior author and Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, added, "Taken together, our results suggest that the ASIC1a gene is a risk gene for panic disorder, as well as for the structure and function of the amygdala and its reaction to threat. They also raise the possibility that drugs that inhibit or modulate ASIC1a might be helpful in the treatment of panic or other forms of anxiety and fear."

Dr. John Krystal, Editor of Biological Psychiatry, commented, "Once again we see that a mechanism that is implicated in the generation of fear and the risk for anxiety disorders has its basis in a fundamental survival mechanism. This important new study continues to build our understanding of the underpinnings of anxiety disorders that affect so many people in our society."

INFORMATION:

The article is "The Human Ortholog of Acid-Sensing Ion Channel Gene ASIC1a Is Associated with Panic Disorder and Amygdala Structure and Function" by Jordan W. Smoller, Patience J. Gallagher, Laramie E. Duncan, Lauren M. McGrath, Stephen A. Haddad, Avram J. Holmes, Aaron B. Wolf, Sidney Hilker, Stefanie R. Block, Sydney Weill, Sarah Young, Eun Young Choi, Jerrold F. Rosenbaum, Joseph Biederman, Stephen V. Faraone, Joshua L. Roffman, Gisele G. Manfro, Carolina Blaya, Dina R. Hirshfeld-Becker, Murray B. Stein, Michael Van Ameringen, David F. Tolin, Michael W. Otto, Mark H. Pollack, Naomi M. Simon, Randy L. Buckner, Dost Öngür, and Bruce M. Cohen (doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.12.018). The article appears in Biological Psychiatry, Volume 76, Issue 11 (December 1, 2014), published by Elsevier.

Notes for editors

Full text of the article is available to credentialed journalists upon request; contact Rhiannon Bugno at +1 214 648 0880 or Biol.Psych@utsouthwestern.edu. Journalists wishing to interview the authors may contact Noah Brown, Public Affairs & Media Relations Officer, Massachusetts General Hospital, at +1 617 643 3907 or nbrown9@partners.org; or Adriana Bobinchock at abobinchock@partners.org.

The authors' affiliations, and disclosures of financial and conflicts of interests are available in the article.

John H. Krystal, M.D., is Chairman of the Department of Psychiatry at the Yale University School of Medicine, Chief of Psychiatry at Yale-New Haven Hospital, and a research psychiatrist at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System. His disclosures of financial and conflicts of interests are available here.

About Biological Psychiatry

Biological Psychiatry is the official journal of the Society of Biological Psychiatry, whose purpose is to promote excellence in scientific research and education in fields that investigate the nature, causes, mechanisms and treatments of disorders of thought, emotion, or behavior. In accord with this mission, this peer-reviewed, rapid-publication, international journal publishes both basic and clinical contributions from all disciplines and research areas relevant to the pathophysiology and treatment of major psychiatric disorders.

The journal publishes novel results of original research which represent an important new lead or significant impact on the field, particularly those addressing genetic and environmental risk factors, neural circuitry and neurochemistry, and important new therapeutic approaches. Reviews and commentaries that focus on topics of current research and interest are also encouraged.

Biological Psychiatry is one of the most selective and highly cited journals in the field of psychiatric neuroscience. It is ranked 5th out of 135 Psychiatry titles and 14th out of 251 Neurosciences titles in the Journal Citations Reports® published by Thomson Reuters. The 2013 Impact Factor score for Biological Psychiatry is 9.472.

About Elsevier

Elsevier is a world-leading provider of information solutions that enhance the performance of science, health, and technology professionals, empowering them to make better decisions, deliver better care, and sometimes make groundbreaking discoveries that advance the boundaries of knowledge and human progress. Elsevier provides web-based, digital solutions -- among them ScienceDirect, Scopus, Elsevier Research Intelligence and ClinicalKey -- and publishes nearly 2,200 journals, including The Lancet and Cell, and over 25,000 book titles, including a number of iconic reference works.

The company is part of Reed Elsevier Group PLC, a world-leading provider of professional information solutions in the Science, Medical, Legal and Risk and Business sectors, which is jointly owned by Reed Elsevier PLC and Reed Elsevier NV. The ticker symbols are REN (Euronext Amsterdam), REL (London Stock Exchange), RUK and ENL (New York Stock Exchange).