(Press-News.org) RIVERSIDE, Calif. - Geckos, found in places with warm climates, have fascinated people for hundreds of years. Scientists have been especially intrigued by these lizards, and have studied a variety of features such as the adhesive toe pads on the underside of gecko feet with which geckos attach to surfaces with remarkable strength.

One unanswered question that has captivated researchers is: Is the strength of this adhesion determined by the gecko or is it somehow intrinsic to the adhesive system? In other words, is this adhesion a result of the entire animal initiating it? Or is the adhesion fundamentally "passive," its strength resulting from the way just the toe pads work?

Biologists at the University of California, Riverside have now conducted experiments in the lab on live and dead geckos to determine the answer. Their experiments show, for the first time, that dead geckos can adhere with the exact same strength as living geckos.

Study results, appearing online Dec. 3 in Biology Letters, could have applications in the field of robotics.

"With regards to geckos, being sticky doesn't require effort," said Timothy E. Higham, an assistant professor of biology, who conducted the research alongside William J. Stewart, a postdoctoral researcher inhis lab. "We found that dead geckos maintain the ability to adhere with the same force as living animals, eliminating the idea that strong adhesion requires active control. Death affects neither the motion nor the posture of clinging gecko feet. We found no difference in the adhesive force or the motion of clinging digits between our before- and after-death experiments."

Higham explained that there have been suggestions in the literature for many years that gecko adhesion at the organismal, or whole-animal, level (where the intact animal initiates adhesion) requires an active component such as muscle activity to push the foot and toes onto the surface in order to enhance adhesion. This has, however, never been tested.

Higham and Stewart took on the challenge and tested the hypothesis. The researchers used a novel device involving a controlled pulling system. This device applies repeatable and steady-increasing pulling forces to the gecko foot in shear. Specifically, the device measures clings by pulling a gecko foot in a highly controlled manner along a vertical acrylic sheet while simultaneously recording shear adhesion with video cameras.

The experiments showed that the adhesive force or motion of a gecko foot when pulled along a vertical surface was similarly high and variable when the gecko was alive and immediately - within 30 minutes - after death.

Geckos can climb a variety of surfaces, including smooth glass. Their sticky toes have inspired climbing devices such as Spider-Man gloves. The toe pads on the underside of gecko feet contain tiny hair-like structures called setae. The setae adhere to contacted surfaces through frictional forces as well as forces between molecules, called van der Waals forces. These tiny structures are so strong that the setae on a single foot can support 20 times the gecko's body weight.

The controlled experiments the researchers performed are the first to show that dead animals maintain the ability to adhere with the same force as living animals. The results refute the notion that actions by a living gecko, such as muscle recruitment or neural activity, are required for gecko feet to generate forces.

"The idea that adhesion can be entirely passive could apply to many different kinds of adhesion," Higham said. "This is clearly a cost-effective way of remaining stationary in a habitat. For example, geckos could perch on a smooth vertical surface and sleep for the night - or day - without using any energy."

The new work suggests that the "active" component of gecko adhesion is actually a reduction of adhesion force when the gecko "hyperextends" its digits - that is, lifts them off the ground by curling up only the tips of the digits while the rest of the foot remains on the surface.

"We found that the dead animals were more likely to experience damage to their adhesive system, which suggests that the active control may actually prevent injury," Stewart aid. "In other words, when the forces become too high, the gecko likely releases the system using its muscles."

INFORMATION:

The research was supported by a grant to Higham from the National Science Foundation. Stewart, the first author of the research paper, is now a postdoctoral scholar at the Whitney Laboratory for Marine Bioscience, the University of Florida.

The University of California, Riverside is a doctoral research university, a living laboratory for groundbreaking exploration of issues critical to Inland Southern California, the state and communities around the world. Reflecting California's diverse culture, UCR's enrollment has exceeded 21,000 students. The campus opened a medical school in 2013 and has reached the heart of the Coachella Valley by way of the UCR Palm Desert Center. The campus has an annual statewide economic impact of more than $1 billion. A broadcast studio with fiber cable to the AT&T Hollywood hub is available for live or taped interviews. UCR also has ISDN for radio interviews. To learn more, call (951) UCR-NEWS.

An efficient method to harvest low-grade waste heat as electricity may be possible using reversible ammonia batteries, according to Penn State engineers.

"The use of waste heat for power production would allow additional electricity generation without any added consumption of fossil fuels," said Bruce E. Logan, Evan Pugh Professor and Kappe Professor of Environmental Engineering. "Thermally regenerative batteries are a carbon-neutral way to store and convert waste heat into electricity with potentially lower cost than solid-state devices."

Low-grade waste heat is an ...

New Rochelle, NY, December 3, 2014--Hereditary angioedema (HAE), a rare genetic disease that causes recurrent swelling under the skin and of the mucosal lining of the gastrointestinal tract and upper airway, usually first appears before 20 years of age. A comprehensive review of the therapies currently available to treat HAE in adults shows that some of these treatments are also safe and effective for use in older children and adolescents. Current and potential future therapies are discussed in a Review article in a special issue of Pediatric Allergy, Immunology, and Pulmonology, ...

Typhoon Hagupit continues to intensify as it continued moving through Micronesia on Dec. 3 triggering warnings. NASA's Aqua satellite passed overhead and captured an image of the strengthening storm while the Rapidscat instrument aboard the International Space Station provided information about the storm's winds.

The International Space Station-RapidScat instrument monitors ocean winds to provide essential measurements used in weather predictions, including hurricanes. "RapidScat measures wind speed and direction over the ocean surface and captured an image of Hagupit ...

This news release is available in French.

Quebec City, December 3, 2014--Researchers at Université Laval's Faculty of Science and Engineering and Centre for Optics, Photonics and Lasers have developed smart textiles able to monitor and transmit wearers' biomedical information via wireless or cellular networks. This technological breakthrough, described in a recent article in the scientific journal Sensors, clears a path for a host of new developments for people suffering from chronic diseases, elderly people living alone, and even firemen and police officers.

A ...

Researchers at North Carolina State University have for the first time mapped human disease-causing pathogens, dividing the world into a number of regions where similar diseases occur.

The findings show that the world can be separated into seven regions for vectored human diseases - diseases that are spread by pests, like mosquito-borne malaria - and five regions for non-vectored diseases, like cholera.

Interestingly, not all of the regions are contiguous. The British Isles and many of its former colonies, such as the United States and Australia, have similar diseases ...

Good news on the panda front: Turns out they're not quite as delicate - and picky - as thought.

Up until now, information gleaned from 30 years worth of scientific literature suggested that pandas were inflexible about habitat. Those conclusions morphed into conventional wisdom and thus have guided policy in China. But a Michigan State University (MSU) research associate has led a deep dive into aggregate data and emerged with evidence that the endangered animal is more resilient and flexible than previously believed.

Vanessa Hull is a postdoctoral research associate ...

Irvine, Calif., Dec. 3, 2014 - High fecal counts frequently detected at so-called "baby beaches" may not be diaper-related. UC Irvine researchers found that during summer months, small drainpipes emptying into enclosed ocean bays have a disproportionate impact on calmer waters. The findings were published Tuesday in the journal Environmental Science & Technology.

Researchers have long known that creeks and tributaries foul coastal waters with major winter storm runoff. But dry seasons like the one that just concluded can spell potential peril, too. Runoff from watering ...

When it comes to getting out of a tricky situation, we humans have an evolutionary edge over other primates. Take, as a dramatic example, the Apollo 13 voyage in which engineers, against all odds, improvised a chemical filter on a lunar module to prevent carbon dioxide buildup from killing the crew.

UC Berkeley scientists have found mounting brain evidence that helps explain how humans have excelled at "relational reasoning," a cognitive skill in which we discern patterns and relationships to make sense of seemingly unrelated information, such as solving problems in unfamiliar ...

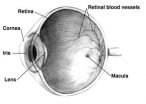

Scientists have developed a new light-sensitive film that could one day form the basis of a prosthetic retina to help people suffering from retinal damage or degeneration. Hebrew University of Jerusalem researchers collaborated with colleagues from Tel Aviv University and Newcastle University in the research, which was published in the journal Nano Letters.

The retina is a thin layer of tissue at the inner surface of the eye. Composed of light-sensitive nerve cells, it converts images to electrical impulses and sends them to the brain. Damage to the retina from macular ...

A new research brief from the US2010 Project probes the status of minorities in American suburbs. Suburbs in 2010 were as racially and ethnically diverse as were central cities in 1980, and that diversity is still increasing. Yet minorities are not finding equal access to the American dream in the suburbs where they live, a lesson illustrated recently by Ferguson, MO.

Suburbia has always been less segregated than central cities. Segregation is slowly declining between suburban blacks and whites, but has stayed about the same for Hispanics and Asians over three decades. ...