World-renowned geneticist from NTU, Professor Stephan Christoph Schuster, who led an international research team from Singapore, United States and Brazil, said this is the first time that the history of mankind populations has been analysed and matched to Earth's climatic conditions over the last 200,000 years.

Their breakthrough findings are published today (4 Dec) in Nature Communications, a prestigious academic journal.

The team has sequenced the genome of five living individuals from a hunter/gatherer tribe in Southern Africa, and compared them with 420,000 genetic variants across 1,462 genomes from 48 ethnic groups of the global population.

Through advanced computation analysis, the team found that these Southern African Khoisan tribespeople are genetically distinct not only from Europeans and Asians, but also from all other Africans.

The team also found that there are individuals of the Khoisan population whose ancestors did not interbreed with any of the other ethnic groups for the last 150,000 years and that Khoisan was the majority group of living humans for most of that time until about 20,000 years ago.

Their findings mean it is now possible to use genetic sequencing to reveal the ancestral lineage of any ethnic group even up to 200,000 years ago, if non-admixed individuals are found, like in the case of the Khoisan. This will show when in history there have been important genetic changes to an ancestral lineage due to intermarriages or geographical migrations that may have occurred over the centuries.

"Khoisan hunter/gatherers in Southern Africa have always perceived themselves as the oldest people," said Prof Schuster, an NTU scientist at the Singapore Centre on Environmental Life Sciences Engineering (SCELSE) and a former Penn State University professor.

"Our study proves that they truly belong to one of mankind's most ancient lineages, and these high quality genome sequences obtained from the tribesmen will help us better understand human population history, especially the understudied branch of mankind such as the Khoisan.

"The new data gathered will also enable scientists to better understand how the human genome has evolved and hopefully lead to more effective treatment options for certain genetic diseases and illnesses."

Of the five tribesmen who were the oldest members of the Ju/'hoansi tribe and other tribes living in protected areas of northwest Namibia, two individuals were found to have a genome which had not admixed with other ethnic groups.

The Ju/'hoansi tribe was made famous in the 80s and 90s by the box-office hit movie series "The Gods Must Be Crazy". The main character of the series was a hunter/gatherer tribesman, played by Nǃxau, a bushman.

The research paper's first author, Dr Hie Lim Kim, a SCELSE senior research fellow, said "it was very surprising that this group apparently did not intermarry with non-Khoisan neighbours for thousands of years". This is because the Khoisan peoples and the rest of modern humanity shared their most recent common ancestor around 150,000 years ago.

The current Khoisan culture and tradition, where marriage occurs either among Khoisan groups or results in female members leaving their tribes after marrying non-Khoisan men, appears to be long-standing.

"A key finding from this study is that even today after 150,000 years, single non-admixed individuals or descendants of those who did not interbreed with separate populations can be identified within the Ju/'hoansi population, which means there might be more of such unique individuals in other parts of the world," added Dr Kim.

The Khoisan tribespeople participating in this study had parts of their genomes sequenced in an earlier study by the same team in 2010. The new study generated complete genome sequences at high quality, which enabled the analysis of admixture and population history. The availability of such high quality Southern African genomes will allow further investigation of the population history of this largely understudied branch of mankind at high resolution.

This research project involving six investigators was led by NTU and Penn State University. Other institutions participating in the study include the Ohio State University and Sao Paulo State University, Brazil.

Moving forward, Prof Schuster added that they will be looking to find more non-admixed individuals who are in the other parts of the world, such as in South Asia and South America, where uncontacted tribes still exist. The team will also be seeking more funding to further their research which will have large impact on the study of life sciences.

INFORMATION:

*More quotes from project partners can be found in Annex 1

Media contact:

Lester Kok

Senior Assistant Manager

Corporate Communications Office

Nanyang Technological University

Email: lesterkok@ntu.edu.sg

About Nanyang Technological University

A research-intensive public university, Nanyang Technological University (NTU) has 33,500 undergraduate and postgraduate students in the colleges of Engineering, Business, Science, Humanities, Arts, & Social Sciences, and its Interdisciplinary Graduate School. It has a new medical school, the Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, set up jointly with Imperial College London.

NTU is also home to world-class autonomous institutes - the National Institute of Education, S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Earth Observatory of Singapore, and Singapore Centre on Environmental Life Sciences Engineering - and various leading research centres such as the Nanyang Environment & Water Research Institute (NEWRI), Energy Research Institute @ NTU (ERI@N) and the Institute on Asian Consumer Insight (ACI).

A fast-growing university with an international outlook, NTU is putting its global stamp on Five Peaks of Excellence: Sustainable Earth, Future Healthcare, New Media, New Silk Road, and Innovation Asia.

Besides the main Yunnan Garden campus, NTU also has a satellite campus in Singapore's science and tech hub, one-north, and a third campus in Novena, Singapore's medical district.

For more information, visit http://www.ntu.edu.sg

ANNEX 1

Additional quotes from project partners:

Assistant Professor Aakrosh Ratan from the University of Virginia said "having identified non-admixed Khoisan individuals, we could compare the effective population size of the Khoisan with that of other humans over more than 100,000 years".

While today's Khoisan hunter/gatherers census size is estimated to be less than 100,000 individuals, the researchers found that the Khoisan for the majority of that time was the most populous human group. The major ethnic groups today in Africa, Asia, and Europe only rose to prominence after overcoming a population decline about 20,000 years ago. This decline did not affect the Khoisan population to the same degree, because they did not share the same habitats and environments as the other human groups.

Webb Miller, Professor for Bioinformatics at Penn State University said: "This report is the first time that the population decline was investigated based on whole genome sequencing of the various human ethnicities".

The reduction in population size likely occurred between 30,000 and 120,000 years ago. Interestingly, this period includes the migration of modern humans out of Africa. While the exodus out of Africa resulted in a bottleneck in itself, the population decline in Western Africa likely had environmental causes.

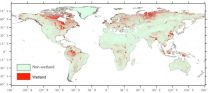

In their report, the researchers investigated the hypothesis that climatic changes resulted in less favourable living conditions, first in Western Africa and later in all of central sub-Saharan Africa.

Assistant Professor Alvaro Montenegro from Ohio State University and the Sao Paulo State University in Brazil, said: "Using a paleoclimate model and data, we were able to show that glaciation in the northern hemisphere resulted in drier conditions in Western/Central Africa, while wetter conditions prevailed in Southern Africa". Similar conditions have been recorded periodically throughout the last several 100,000's of years and likely had a major impact on the ecosystems of the world, he added.

George Perry, an Assistant Professor for Anthropology at Penn State University said "the decline in population was much less pronounced for the ancestral Khoisan populations living in Southern Africa". The reason being suggested in the new study, was that the wetter climates in the Khoisan-inhabited parts of Southern Africa, were more favourable.

The study indicates how perilous modern human survival has been throughout history, as is shown by the extinction of many populations of fauna in the same period of time by other documentation. The climate appears to have been a major factor for the formation of favourable environments that sustained populations of human hunter/gatherers.