(Press-News.org) Magnetite (or Fe3O4) is an elaborate kind of rust - a regular lattice of oxygen and iron atoms. But this material plays an increasingly important role as a catalyst, in electronic devices and in medical applications.

Scientists at the Vienna University of Technology have now shown that the atomic structure of the magnetite surface, which everybody had assumed to be well-established, has in fact been wrong all along. The properties of magnetite are governed by missing iron atoms in the sub-surface layer. "It turns out that the surface of Fe3O4 is not Fe3O4 at all, but rather Fe11O16", says Professor Ulrike Diebold, head of the metal-oxide-research group at TU Wien (Vienna). The new findings have now been published in the journal Science.

The Material That Just Won't Behave

Perhaps the most surprising property of the magnetite surface is that single atoms placed on the surface, for instance gold or palladium, stay perfectly in place instead of balling up and forming a nanoparticle. This effect makes the surface an extremely efficient catalyst for chemical reactions - but nobody had ever been able to tell why magnetite behaves that way. "Also, Fe3O4-based electronics never function quite as well as they should", says Gareth Parkinson (TU Wien). "Because materials interact with their environment through the surface, it's really important to understand the structure of the surface and why it forms."

Very often, the properties of metal oxides depend on oxygen vacancies in the topmost atomic layers. Depending on the environment, some oxygen atoms on the surface may be missing. This can dramatically influence the electronic properties of the material. "Everyone in our community thinks about missing oxygen atoms. That is why it took us quite a while to figure out that it is in fact missing iron atoms that do the trick", says Gareth Parkinson.

It's Not the Oxygen, It's the Metal

Instead of a fixed structure of metal atoms with built-in oxygen atoms, one rather has to think of iron-oxides as a well-defined oxygen structure with little metal atoms hiding inside. Directly below the outermost atomic layer, the crystal structure is rearranged and some iron atoms are absent.

It is precisely above such places of missing iron atoms that other metal atoms attach. These iron-vacancy-sites are regularly spaced, and so there is always some well-defined distance between gold or palladium atoms attaching to the surface. This explains why magnetite surfaces prevent these atoms from forming clusters.

The idea of completely re-thinking the crystal structure of magnetite was rather bold, and therefore the scientists analysed their theory very carefully. Quantum simulations were carried out on large supercomputers to show that the proposed structure was indeed physically reasonable. After that, electron diffraction measurements were done together with researchers at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany.

"By scattering slow electrons at surfaces, one can measure how well the actual crystal structure of the material agrees with a theoretical model", says Ulrike Diebold. This agreement is quantified by the so-called "R-value". "For very well-known structures, one may achieve an R-value of 0.1 or 0.15. For magnetite, nobody had ever managed to get anything better than 0.3, and people said it just could not be done." But the new magnetite structure with missing iron atoms agrees very well with the experimental data, yielding an R-value of 0.125.

Magnetite Is Just the Beginning

Metal oxides are widely known to be technologically important but extremely complicated to describe. "Our results show that there is no need to despair. Metal oxides can be modelled quite accurately after all, but maybe not in the way one might expect at first glance", says Gareth Parkinson. The scientists expect that their findings do not just apply to iron oxide but also to oxides of cobalt, manganese or nickel. Re-thinking their crystal structures could possibly boost iron-oxide research in many areas and lead to applications in chemical catalysis, electronics or medicine.

The research project is building bridges between physics and chemistry. TU Wien has set up the doctoral college "Solids4fun" to foster close interdisciplinary collaborations in the field of materials and surface science.

INFORMATION:

http://solids4fun.tuwien.ac.at/

Further Information

Prof. Ulrike Diebold

Institute for Applied Physics

Vienna University of Technology

Wiedner Hauptstraße 8, 1040 Vienna

T: +43-1-58801-13425

ulrike.diebold@tuwien.ac.at

Gareth Parkinson, PhD

Institute for Applied Physics

Vienna University of Technology

Wiedner Hauptstraße 8, 1040 Vienna

T: +43-1-58801-13473

gareth.parkinson@tuwien.ac.at

Highly expressed in the testis, a gene named Ranbp9 has been found to play a critical role in male fertility by controlling the correct expression of thousands of genes required for successful sperm production. A group of researchers led by Professor Wei Yan, at the University of Nevada School of Medicine has discovered that a loss of function of Ranbp9 leads to severely reduced male fertility due to disruptions in sperm development. A paper reporting this finding was published in PLOS Genetics on December 4, 2014.

Male infertility affects 1 out of 20 men of reproductive ...

A genetic variant which causes smokers to smoke more heavily has been shown to be associated with increased body mass index (BMI) - but only in those who have never smoked, according to new research led by the University of Bristol, UK and published today in PLOS Genetics.

It is likely that this finding has not come to light before because it has been masked by the effect of smoking, which acts to reduce BMI.

Professor Marcus Munafo from Bristol's School of Experimental Psychology and colleagues studied a variant in the CHRNA5-A3-B4 gene cluster which is known to increase ...

Researchers from the Medical Research Council Lifecourse Epidemiology Unit (MRC LEU), University of Southampton have shed new light on how grip strength changes across the lifespan. Previous work has shown that people with weaker grip strength in midlife and early old age are more likely to develop problems, such as loss of independence and to have shorter life expectancy. However, there is little information on what might be considered a normal grip strength at different ages.

This latest research, which combined information from 12 British studies and is published in ...

An international team, including scientists from DESY, has caught a light sensitive biomolecule at work with an X-ray laser. The study proves that X-ray lasers can capture the fast dynamics of biomolecules in ultra slow-motion, as the scientists led by Prof. Marius Schmidt from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee write in the journal Science. "Our study paves the way for movies from the nano world with atomic spatial resolution and ultrafast temporal resolution", says Schmidt.

The researchers used the photoactive yellow protein (PYP) as a model system. PYP is a receptor ...

The temperature of the seawater around Antarctica is rising according to new research from the University of East Anglia.

New research published today in the journal Science shows how shallow shelf seas of West Antarctica have warmed over the last 50 years.

The international research team say that this has accelerated the melting and sliding of glaciers in the area, and that there is no indication that this trend will reverse.

It also reveals that other Antarctic areas, which have not yet started to melt, could experience melting for the first time with consequences ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Scientists may have solved a long-standing enigma known as the African Humid Period - an intense increase in cumulative rainfall in parts of Africa that began after a long dry spell following the end of the last ice age and lasting nearly 10,000 years.

In a new study published this week in Science, an international research team linked the increase in rainfall in two regions of Africa thousands of years ago to an increase in greenhouse gas concentrations. The study was funded by the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy.

The ...

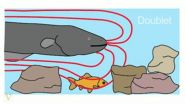

A long-held assumption about the Earth is discussed in today's edition of Science, as Don L. Anderson, an emeritus professor with the Seismological Laboratory of the California Institute of Technology, and Scott King, a professor of geophysics in the College of Science at Virginia Tech, look at how a layer beneath the Earth's crust may be responsible for volcanic eruptions.

The discovery challenges conventional thought that volcanoes are caused when plates that make up the planet's crust shift and release heat.

Instead of coming from deep within the interior of the ...

VIDEO:

Vanderbilt biologist Kenneth Catania describes his discovery that the electroshock system used by the electric eel to detect and immobilize prey is uncannily similar to the Taser.

Click here for more information.

The electric eel - the scaleless Amazonian fish that can deliver an electrical jolt strong enough to knock down a full-grown horse - possesses an electroshock system uncannily similar to a Taser.

That is the conclusion of a nine-month study of the way in which ...

The "survival of the fittest" principle applies to cells in a tissue - rapidly growing and dividing cells are the fit ones. A relatively less fit cell, even if healthy and viable, will be eliminated by its more fit neighbors. Importantly, this selection mechanism is only activated when cells with varying levels of fitness are present in the same tissue. If a tissue only consists of less fit cells, then no so-called cell competition occurs. Molecular biologists from the University of Zurich and Columbia University are the first researchers to demonstrate in a study published ...

Since 2010, detections of Asian Carp environmental DNA or "eDNA" have warned scientists, policymakers, and the public that these high-flying invaders are knocking on the Great Lakes' door. Scientists capture tiny DNA-containing bits from water and use genetic analysis to determine if any Asian Carp DNA is present. New research published by Notre Dame scientists shows that the tools currently used for Asian Carp eDNA monitoring often fail to detect the fish. By comparison, the new eDNA methods described in this study capture and detect Asian Carp eDNA more effectively.

The ...