(Press-News.org) PHILADELPHIA -Researchers at Penn Medicine, in collaboration with a multi-center international team, have shown that a protease inhibitor, simeprevir, a once a day pill, along with interferon and ribavirin has proven as effective in treating chronic Hepatitis C virus infection (HCV) as telaprevir with interferon and ribavirin, the standard of care in developing countries. Further, simeprevir proved to be simpler for patients and had fewer adverse events. The complete study is now available online and is scheduled to publish in January 2015 in The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

"The observations from the study present simeprevir, peginterferon and ribavirin as a good therapeutic option for regions of the world where all-oral therapies are unavailable or cost prohibitive," says Rajender Reddy, MD, professor of Medicine and director of Hepatology the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. "This is the only study we are aware of that directly compares telaprevir to simeprevir." Telaprevir, another protease inhibitor, is an oral HCV medication taken up to three times daily, has multiple side effects and is less accessible than simeprevir. Simeprevir is manufactured by Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

In the U.S. and other countries where access to the latest research and treatment for HCV is available, physicians have moved towards all-oral therapy and away from interferon-based therapies such as these, as they are known to come with a significant number of side effects and are not as effective.

This Phase 3 randomized, double-blind study included 763 adults with chronic HCV genotype 1 infection, a form of the virus found in up to 75 percent of infections, and compensated liver diseases, who had previously not responded or only partially responded to at least one course of peginterferon and ribavirin.

Patients were randomized to receive simeprevir plus telaprevir placebo (379) or telaprevir plus simeprevir placebo (384) in combination with peginterferon and ribavirin for 12 weeks followed by 36 weeks of peginterferon and ribavirin alone.

The regimen of simeprevir with peginterferon and ribavirin proved to be as good as telaprevir and peginterferon and ribavirin, with 54 percent of patients in the simeprevir group versus 55 percent in the telaprevir group achieving a sustained virologic response (SVR), a lowering of the amount of virus in the body, 12 weeks after cessation of therapy. In prior partial responders, SVR was achieved in 70 percent versus 68 percent and in 44 percent versus 46 percent of previous non-responders following treatment with simeprevir and peginterferon and ribavirin and telaprevir and peginterferon and ribavirin treatment, respectively.

Sixty-nine percent of patients experienced simeprevir-related adverse events while 86 percent in the telaprevir group reported telaprevir-related adverse events.

"HCV treatment has been a moving target, especially for those who do not have access to or the ability to pay for the latest treatment options," says Reddy. "With this study, we showed that simeprevir once a day was well-tolerated in genotype 1 infected previous non-responders, making it a viable alternative to telaprevir for a segment of patients with HCV."

INFORMATION:

This study was funded by Janssen Research and Development.

Dr. Reddy receives consulting fees and research support from Janssen.

Penn Medicine is one of the world's leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, and excellence in patient care. Penn Medicine consists of the Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (founded in 1765 as the nation's first medical school) and the University of Pennsylvania Health System, which together form a $4.3 billion enterprise.

The Perelman School of Medicine has been ranked among the top five medical schools in the United States for the past 17 years, according to U.S. News & World Report's survey of research-oriented medical schools. The School is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $392 million awarded in the 2013 fiscal year.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System's patient care facilities include: The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania -- recognized as one of the nation's top "Honor Roll" hospitals by U.S. News & World Report; Penn Presbyterian Medical Center; Chester County Hospital; Penn Wissahickon Hospice; and Pennsylvania Hospital -- the nation's first hospital, founded in 1751. Additional affiliated inpatient care facilities and services throughout the Philadelphia region include Chestnut Hill Hospital and Good Shepherd Penn Partners, a partnership between Good Shepherd Rehabilitation Network and Penn Medicine.

Penn Medicine is committed to improving lives and health through a variety of community-based programs and activities. In fiscal year 2013, Penn Medicine provided $814 million to benefit our community.

BELLINGHAM, Washington, USA, and COLCHESTER, UK -- Swimmers looking to monitor and improve technique and patients striving to heal injured muscles now have a new light-based tool to help reach their goals. A research article by scientists at the University of Essex in Colchester and Artinis Medical Systems published today (5 December) in the Journal of Biomedical Optics (JBO) describes the first measurements of muscle oxygenation underwater and the development of the enabling technology.

The article, "Underwater near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy measurements of muscle ...

Increases in excess fat adversely affect multiple cardiometabolic risk markers even in lean young adults according to a new study published this week in PLOS Medicine. The study by Peter Würtz from the University of Oulu, Finland, and colleagues suggests that, even within the range of body-mass index (BMI) considered to be healthy, there is no threshold below which a BMI increase does not adversely affect the metabolic profile of an individual.

Adiposity, or having excess body fat, is a growing global threat to public health. Compared to people with a lean body ...

December 9, 2014 -- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a common cause of hospital-acquired infections, with the largest burden of infections occurring in under-resourced hospitals. While genome sequencing has previously been applied in well-resourced clinical settings to track the spread of MRSA, transmission dynamics in settings with more limited infection control is unknown. In a study published online today in Genome Research, researchers used genome sequencing to understand the spread of MRSA in a resource-limited hospital with high transmission rates.

Patients ...

SAN FRANCISCO (DECEMBER 9, 2014) -Common variations in four genes related to brain inflammation or cells' response to damage from oxidation may contribute to the problems with memory, learning and other cognitive functions seen in children treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), according to a study led by researchers from Boston Children's Hospital, The Children's Hospital at Montefiore, and Dana-Farber/Boston Children's Cancer and Blood Disorders Center.

The data, presented at the 56th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology (abstract #856), suggest ...

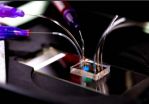

A team of Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) investigators has identified what may be a biomarker predicting the development of the dangerous systemic infection sepsis in patients with serious burns. In their report in the open-access journal PLOS ONE, the researchers describe finding that the motion through a microfluidic device of the white blood cells called neutrophils is significantly altered two to three days before sepsis develops, a finding that may provide a critically needed method for early diagnosis.

"Neutrophils are the major white blood cell protecting ...

Timing is key for brain cells controlling a complex motor activity like the singing of a bird, finds a new study published by PLOS Biology.

"You can learn much more about what a bird is singing by looking at the timing of neurons firing in its brain than by looking at the rate that they fire," says Sam Sober, a biologist at Emory University whose lab led the study. "Just a millisecond difference in the timing of a neuron's activity makes a difference in the sound that comes out of the bird's beak."

The findings are the first to suggest that fine-scale timing of neurons ...

Researchers from the University of Cambridge have used genome sequencing to monitor how the spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) occurs in under-resourced hospitals. By pinpointing how and when MRSA was transmitted over a three-month period at a hospital in northeast Thailand, the researchers are hoping their results will support evidence-based policies around infection control.

MRSA is a common cause of hospital-acquired infections, with the largest burden of infections occurring in under-resourced hospitals in the developing world. Whereas genome ...

The availability of a trace nutrient can cause genome-wide changes to how organisms encode proteins, report scientists from the University of Chicago in PLoS Biology on Dec. 9. The use of the nutrient - which is produced by bacteria and absorbed in the gut - appears to boost the speed and accuracy of protein production in specific ways.

"This is in some sense a 'you are what you eat' hypothesis,"' said senior study author D. Allan Drummond, PhD, assistant professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at the University of Chicago. "This nutrient that is absorbed through ...

AUDIO:

Nitrous oxide, often called laughing gas, has been used in medicine and in dentistry for more than 150 years. But researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis...

Click here for more information.

Nitrous oxide, or laughing gas, has shown early promise as a potential treatment for severe depression in patients whose symptoms don't respond to standard therapies. The pilot study, at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, is believed to ...

A new policy paper by a University of York academic calls for limits on the influence of the drinks industry in shaping alcohol policy because it has a 'fundamental conflict of interest'.

The article by Professor Jim McCambridge, of the Department of Health Sciences at York and academics at King's College London and the University of Newcastle, New South Wales, is published in this week's PLOS Medicine.

It says the concept of harm reduction has been co-opted by industry interests in public health debates about reducing the damage caused by alcohol. The paper argues ...