(Press-News.org) CORVALLIS, Ore. - Nitrous oxide (N2O) is an important greenhouse gas that doesn't receive as much notoriety as carbon dioxide or methane, but a new study confirms that atmospheric levels of N2O rose significantly as the Earth came out of the last ice age and addresses the cause.

An international team of scientists analyzed air extracted from bubbles enclosed in ancient polar ice from Taylor Glacier in Antarctica, allowing for the reconstruction of the past atmospheric composition. The analysis documented a 30 percent increase in atmospheric nitrous oxide concentrations from 16,000 years ago to 10,000 years ago. This rise in N2O was caused by changes in environmental conditions in the ocean and on land, scientists say, and contributed to the warming at the end of the ice age and the melting of large ice sheets that then existed.

The findings add an important new element to studies of how Earth may respond to a warming climate in the future. Results of the study, which was funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation and the Swiss National Science Foundation, are being published this week in the journal Nature.

"We found that marine and terrestrial sources contributed about equally to the overall increase of nitrous oxide concentrations and generally evolved in parallel at the end of the last ice age," said lead author Adrian Schilt, who did much of the work as a post-doctoral researcher at Oregon State University. Schilt then continued to work on the study at the Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research at the University of Bern in Switzerland.

"The end of the last ice age represents a partial analog to modern warming and allows us to study the response of natural nitrous oxide emissions to changing environmental conditions," Schilt added. "This will allow us to better understand what might happen in the future."

Nitrous oxide is perhaps best known as laughing gas, but it is also produced by microbes on land and in the ocean in processes that occur naturally, but can be enhanced by human activity. Marine nitrous oxide production is linked closely to low oxygen conditions in the upper ocean and global warming is predicted to intensify the low-oxygen zones in many of the world's ocean basins. N2O also destroys ozone in the stratosphere.

"Warming makes terrestrial microbes produce more nitrous oxide," noted co-author Edward Brook, an Oregon State paleoclimatologist whose research team included Schilt. "Greenhouse gases go up and down over time, and we'd like to know more about why that happens and how it affects climate."

Nitrous oxide is among the most difficult greenhouse gases to study in attempting to reconstruct the Earth's climate history through ice core analysis. The specific technique that the Oregon State research team used requires large samples of pristine ice that date back to the desired time of study - in this case, between about 16,000 and 10,000 years ago.

The unusual way in which Taylor Glacier is configured allowed the scientists to extract ice samples from the surface of the glacier instead of drilling deep in the polar ice cap because older ice is transported upward near the glacier margins, said Brook, a professor in Oregon State's College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences.

The scientists were able to discern the contributions of marine and terrestrial nitrous oxide through analysis of isotopic ratios, which fingerprint the different sources of N2O in the atmosphere.

"The scientific community knew roughly what the N2O concentration trends were prior to this study," Brook said, "but these findings confirm that and provide more exact details about changes in sources. As nitrous oxide in the atmosphere continues to increase - along with carbon dioxide and methane - we now will be able to more accurately assess where those contributions are coming from and the rate of the increase."

Atmospheric N2O was roughly 200 parts per billion at the peak of the ice age about 20,000 years ago then rose to 260 ppb by 10,000 years ago. As of 2014, atmospheric N2Owas measured at about 327 ppb, an increase attributed primarily to agricultural influences.

Although the N2O increase at the end of the last ice age was almost equally attributable to marine and terrestrial sources, the scientists say, there were some differences.

"Our data showed that terrestrial emissions changed faster than marine emissions, which was highlighted by a fast increase of emissions on land that preceded the increase in marine emissions," Schilt pointed out. "It appears to be a direct response to a rapid temperature change between 15,000 and 14,000 years ago."

That finding underscores the complexity of analyzing how Earth responds to changing conditions that have to account for marine and terrestrial influences; natural variability; the influence of different greenhouse gases; and a host of other factors, Brook said.

"Natural sources of N2O are predicted to increase in the future and this study will help up test predictions on how the Earth will respond," Brook said.

INFORMATION:

Note to Reporters: Financial support was provided by the Swiss and U.S. National Science Foundations (NSF), including a Swiss NSF fellowship for prospective researchers (139404) to A.S., U.S. NSF grant PLR08-38936 to E.J.B., and U.S. NSF grant PLR08-39031 to J.P.S.

An images is available to illustrate this article at: https://flic.kr/p/poWBsJ

In a ground-breaking paper published in Nature, they show that the three protein complexes act in relay to regulate cell division: reactivation of one leads to the second becoming active.

Cells rely on control systems to make sure that each aspect of the cell division cycle occurs in the correct order. Following successful segregation of the genomes in mitosis, each must return to its pre-division state in a process called mitotic exit. Mitotic exit is irreversible for all multicellular organisms. Loss of cell cycle control during this process - leading to unregulated ...

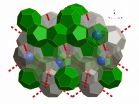

Clathrates are now known to store enormous quantities of methane and other gases in the permafrost as well as in vast sediment layers hundreds of metres deep at the bottom of the ocean floor. Their potential decomposition could therefore have significant consequences for our planet, making an improved understanding of their properties a key priority.

In a paper published in Nature this week, scientists from the University of Göttingen and the Institut Laue Langevin (ILL) report on the first empty clathrate of this type, consisting of a framework of water molecules ...

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Using a gene-editing system originally developed to delete specific genes, MIT researchers have now shown that they can reliably turn on any gene of their choosing in living cells.

This new application for the CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing system should allow scientists to more easily determine the function of individual genes, according to Feng Zhang, the W.M. Keck Career Development Professor in Biomedical Engineering in MIT's Departments of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and Biological Engineering, and a member of the Broad Institute and MIT's McGovern Institute ...

Anticipated changes in climate will push West Coast marine species from sharks to salmon northward an average of 30 kilometers per decade, shaking up fish communities and shifting fishing grounds, according to a new study published in Progress in Oceanography.

The study suggests that shifting species will likely move into the habitats of other marine life to the north, especially in the Gulf of Alaska and Bering Sea. Some will simultaneously disappear from areas at the southern end of their ranges, especially off Oregon and California.

"As the climate warms, the species ...

For the firefighters and rescue workers conducting the rescue and cleanup operations at Ground Zero from September 2001 to May 2002, exposure to hazardous airborne particles led to a disturbing "WTC cough" -- obstructed airways and inflammatory bronchial hyperactivity -- and acute inflammation of the lungs. At the time, bronchoscopy, the insertion of a fiber optic bronchoscope into the lung, was the only way to obtain lung samples. But this method is highly invasive and impractical for screening large populations.

That motivated Prof. Elizabeth Fireman of Tel Aviv University's ...

There are pros and cons to the support that victimized teenagers get from their friends. Depending on the type of aggression they are exposed to, such support may reduce youth's risk for depressive symptoms. On the other hand, it may make some young people follow the delinquent example of their friends, says a team of researchers from the University of Kansas in the US, led by John Cooley. Their findings are published in Springer's Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment.

Adolescence is an important time during which youth establish their social identity. ...

Patients with heart disease who receive transfusions during surgeries do just as well with smaller amounts of blood and face no greater risk of dying from other diseases than patients who received more blood, according to a new Rutgers study.

The research, published in the journal Lancet, measures overall mortality and mortality from cardiovascular disease, cancer and severe infection, and offers new validation to a recent trend toward smaller transfusions.

For the study, led by Jeffrey Carson, chief of the Division of Internal Medicine at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson ...

A class of drug for treating arthritis - all but shelved over fears about side effects - may be given a new lease of life, following the discovery of a possible way to identify which patients should avoid using it.

The new study, led by Imperial College London and published in the journal Circulation, sheds new light on the 10-year-old question of how COX-2 inhibitors - a type of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) - can increase the risk of heart attack in some people.

NSAIDs - which include very familiar drugs such as ibuprofen, diclofenac and aspirin - are ...

Typhoon Hagupit soaked the Philippines, and a NASA rainfall analysis indicated the storm dropped almost 19 inches in some areas. After Hagupit departed the Philippines as a tropical storm, NASA's Terra satellite passed over and captured a picture of the storm curled up like a cat waiting to pounce when it landfalls in Vietnam on Dec. 11.

The Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission or TRMM satellite, managed by NASA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency gathered over a week of rainfall data on Hagupit. That rainfall data along with data from other satellites was compiled ...

COLUMBIA, Mo. - Previous cancer research has revealed that women are less likely than men to suffer from non-sex specific cancers such as cancer of the colon, pancreas and stomach. Scientists theorized that perhaps this trend was due to a protecting effect created by female hormones, such as estrogen, that help prevent tumors from forming. Now, researchers at the University of Missouri have found evidence suggesting that the male hormone testosterone may actually be a contributing factor in the formation of colon cancer tumors.

In his study, James Amos-Landgraf, an assistant ...