(Press-News.org) An interstellar mystery of why stars form has been solved thanks to the most realistic supercomputer simulations of galaxies yet made.

Theoretical astrophysicist Philip Hopkins of the California Institute of Technology (CalTech) led research that found that stellar activity -- like supernova explosions or even just starlight -- plays a big part in the formation of other stars and the growth of galaxies.

"Feedback from stars, the collective effects from supernovae, radiation, heating, pushing on gas, and stellar winds can regulate the growth of galaxies and explain why galaxies have turned so little of the available supply of gas that they have into stars," Hopkins said.

Galaxy simulations were tested on the Stampede supercomputer of the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC), an Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment-allocated (XSEDE) resource funded by the National Science Foundation.

The initial results were published September of 2014 in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. Hopkins's work was funded by the National Science Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and a NASA Einstein Postdoctoral Fellowship.

The mystery begins in interstellar space, the vast space between stars. There dwell enormous clouds of molecules, mainly hydrogen, with the mass of thousands or even millions of Suns. These molecular gas clouds condense and give birth to stars.

What's puzzled astrophysicists since the 1970s is their observations that only a small fraction of matter in the clouds becomes a star. The best computer simulations, however, predicted nearly all of a cloud's matter would cool and become a star.

"That's really what we were trying to figure out and address, for the first time, by putting in the real physics of what we know stars do to the gas around them," Hopkins said.

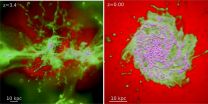

A multi-institution collaboration formed with members from CalTech, U.C. Berkeley, U.C. San Diego, U.C. Irvine, Northwestern, and the University of Toronto. They produced a new set of supercomputer galaxy models called FIRE or Feedback in Realistic Environments. It focused the computing power on small scales of just a few light years across.

"We started by simulating just single stars in little patches of the galaxy, where we trace every single explosion," Hopkins explained. "That lets you build a model that you can put into a simulation of a whole galaxy at a time. And then you build that up into simulations of a chunk of the universe at a time."

Hopkins developed the simulation code locally on a cluster at CalTech, but the Stampede supercomputer did the lion's share of the computation.

"Almost all of these simulations were run on XSEDE resources," Hopkins said. "In particular the Stampede supercomputer at TACC was the workhorse of these simulations...Stampede was an ideal machine -- it was fast, it had large shared memory nodes with a lot of processors per node and good memory per processor. And that let us run this on a much faster timescale than we had originally anticipated. Combined with improvements we made to the parallelization of the problem, we were able to run this problem on thousands of CPUs at a time, which is record-breaking for this type of problem," Hopkins said.

The realism achieved by the FIRE galaxy simulations surprised Hopkins. Past work with sub-grid models of how supernovae explode and how radiation interacts with gas required manually tweaking the model after each run.

"My real jaw-dropping moment," Hopkins said, "was when we put the physics that we thought had been missing from the previous models in without giving ourselves a bunch of nobs to turn. We ran it and it actually looked like a real galaxy. And it only had a few percent of material that turned into stars, instead of all of it, as in the past."

FIRE has mostly simulated the more typical and small galaxies, and Hopkins wants to build on its success. "We want to explore the odd balls, the galaxies that we see that are of strange sizes or masses or have unusual properties in some other way," Hopkins said.

Hopkins also wants to model galaxies with supermassive black holes at the center, like our own Milky Way. "In the process of falling in, before matter actually gets trapped by the black hole and nothing can escape, it turns out that for the most massive galaxies, this is even more energy than released by all the stars in the galaxy. It's almost certainly important. But it's at the edge, and we're just starting to think about simulating those giant galaxies," Hopkins said.

INFORMATION:

Unlike mammals, birds have no external ears. The outer ears of mammals play an important function in that they help the animal identify sounds coming from different elevations. But birds are also able to perceive whether the source of a sound is above them, below them, or at the same level. Now a research team from Technische Universität München (TUM) has discovered how birds are able to localize these sounds, namely by utilizing their entire head. Their findings were published recently in the PLOS ONE journal.

It is springtime, and two blackbirds are having ...

NEW YORK, NY - Patients with operable kidney cancers were more likely to have a partial nephrectomy -- the recommended treatment for localized tumors -- when treated in hospitals that were early adopters of robotic surgery, according to a new study.

Researchers from NYU Langone Medical Center and elsewhere, publishing online December 11 in the journal Medical Care, report that by 2008, hospitals that had adopted robotic surgery at the start of the current century (between 2001 and 2004) performed partial nephrectomies in 38% of kidney cancer cases compared to late adopters ...

Novel research reveals that the risk of acute gout attacks is more than two times higher during the night or early morning hours than it is in the daytime. The study published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, a journal of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), confirms that nocturnal attacks persist even among those who did not consume alcohol and had a low amount of purine intake during the 24 hours prior to the gout attack.

The body produces uric acid from the process of breaking down purines--natural substances in cells in the body and in most foods--with especially ...

Parkinson's disease sufferers have a different microbiota in their intestines than their healthy counterparts, according to a study conducted at the University of Helsinki and the Helsinki University Central Hospital (HUCH).

"Our most important observation was that patients with Parkinson's have much less bacteria from the Prevotellaceae family; unlike the control group, practically no one in the patient group had a large quantity of bacteria from this family," states DMSc Filip Scheperjans, neurologist at the HUCH Neurology Clinic.

The researchers have not yet ...

A team of researchers led by North Carolina State University has found that stacking materials that are only one atom thick can create semiconductor junctions that transfer charge efficiently, regardless of whether the crystalline structure of the materials is mismatched - lowering the manufacturing cost for a wide variety of semiconductor devices such as solar cells, lasers and LEDs.

"This work demonstrates that by stacking multiple two-dimensional (2-D) materials in random ways we can create semiconductor junctions that are as functional as those with perfect alignment" ...

Researchers have found new evidence that explains how some aspects of our personality may affect our health and wellbeing, supporting long-observed associations between aspects of human character, physical health and longevity.

A team of health psychologists at The University of Nottingham and the University of California in Los Angeles carried out a study to examine the relationship between certain personality traits and the expression of genes that can affect our health by controlling the activity of our immune systems.

The study did not find any results to support ...

Could there finally be tangible evidence for the existence of dark matter in the Universe? After sifting through reams of X-ray data, scientists in EPFL's Laboratory of Particle Physics and Cosmology (LPPC) and Leiden University believe they could have identified the signal of a particle of dark matter. This substance, which up to now has been purely hypothetical, is run by none of the standard models of physics other than through the gravitational force. Their research will be published next week in Physical Review Letters.

When physicists study the dynamics of galaxies ...

In the hunt for better knowledge on the aging process, researchers from Lund University have now enlisted the help of small birds. A new study investigates various factors which affect whether chicks are born with long or short chromosome ends, called telomeres.

The genetic make-up of our cells consists of genes lined up on chromosomes. The ends of the chromosomes are called telomeres, and they protect the chromosomes from sticking to each other. The longer the telomeres, the longer time the chromosomes are able to function. And conversely, the shorter these ends, ...

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - Invasive plant and animal species can cause dramatic and enduring changes to the geography and ecology of landscapes, a study from Purdue University and the University of Kentucky shows.

A review of studies on how life forms interact with and influence their surroundings concluded that invasive species can alter landscapes in myriad ways and with varying degrees of severity. These changes can be quick, large-scale and "extremely difficult" to reverse, said study author Songlin Fei, a Purdue associate professor of quantitative ecology.

"Invaders ...

A species of small fish uses a homemade coral-scented cologne to hide from predators, a new study has shown, providing the first evidence of chemical camouflage from diet in fish.

Filefish evade predators by feeding on their home corals and emitting an odor that makes them invisible to the noses of predators, the study found. Chemical camouflage from diet has been previously shown in insects, such as caterpillars, which mask themselves by building their exoskeletons with chemicals from their food. The new study shows that animals don't need an exoskeleton to use chemical ...