Herpes virus rearranges telomeres to improve viral replication

Findings lead to better understanding of how viruses replicate and role of telomeres in stopping viruses

2014-12-11

(Press-News.org) PHILADELPHIA - (Dec. 11, 2014) - A team of scientists, led by researchers at The Wistar Institute, has found that an infection with herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) causes rearrangements in telomeres, small stretches of DNA that serve as protective ends to chromosomes. The findings, which will be published in the Dec. 24 edition of the journal Cell Reports, show that this manipulation of telomeres may explain how viruses like herpes are able to successfully replicate while also revealing more about the protective role that telomeres play against other viruses.

"We know that telomeres play a very important part in the lifespan of a cell," said Paul M. Lieberman, Ph.D., Hilary Koprowski, M.D., Endowed Professor and Professor and Program Leader of the Gene Expression and Regulation Program at The Wistar Institute. "We wanted to know whether they also play a role in either viral replication or protection from viruses, and our findings suggest - at least in the case of the herpes simplex virus - that this may indeed be the case."

Telomeres are often compared to the clear tips of shoelaces because they protect the end of chromosomes - the keepers of our vital genetic information - and prevent them from fraying and breaking, thus preserving their ability to pass on necessary genetic information. Previously, Lieberman's lab at Wistar has shown that viral DNA replication and maintenance share some common features with telomeres.

"Telomeres may serve as a barrier to viral replication," Lieberman said. "We wanted to explore whether that protection was at a physical level or a more molecular level."

Among the viruses Lieberman and his lab have decided to study is HSV-1, a particularly aggressive virus that replicates in the nucleus of a healthy cell where chromosomes and their telomeres reside. HSV-1 is a common virus that causes cold sores but can also cause more serious diseases including blindness and encephalitis. In the United States, approximately 65 percent of the population has antibodies to this particular strain of the virus as well as latent infections that can periodically reactivate to cause clinical symptoms. There is no vaccine for preventing HSV-1 infection and reactivation, and only a few effective treatments for the virus are available.

As detailed in the study, the Lieberman lab found that HSV-1 is able to induce the transcription of telomere repeat-containing RNA (TERRA). This is followed by the virus degrading a telomere protein called TPP1 - part of a complex of proteins responsible for protection called "telomere sheltering" - which results in the loss of the telomere repeat DNA signal. When TPP1 becomes inhibited, the virus is able to increase its ability to replicate, suggesting that TPP1 normally provides some sort of protective function against this virus. HSV-1 is able to replicate more efficiently by disabling this protection. Finally, the virus uses a replication protein called ICP8 that works with the manipulated telomeric proteins to promote viral genomic replication.

"This study expands our knowledge of telomeres further in two very important ways," Lieberman said. "First, it gives us an indication that some viruses are able to manipulate telomeres specifically in order to replicate. Second, it appears that proteins like TPP1 provide very specific protective functions. These findings allow us to ask additional questions and better understand just how telomeres may protect cells from viral infection."

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by an American Heart Association grant (11SDG5330017) and a National Institutes of Health grant (RO1CA140652). This work was also supported by the Institute's National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA010815) and the Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement Program, Pennsylvania Department of Health.

Members of the Lieberman laboratory who co-authored this study include Zhong Deng, Olga Vladimirova, Jayaraju Dheekollu, and Zhuo Wang. Other authors from The Wistar Institute included Scott E. Hensley, Susan Janicki, Jaclyn L. Myers, and Alyshia Newhart. Other authors included Eui Tae Kim and Matthew D. Weitzman from the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine and The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia; Dongmei Liu and Jennifer Moffat from the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at State University of New York Upstate Medical University; Nigel W. Fraser from the Department of Microbiology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania; and David M. Knipe from the Department of Microbiology and Immunobiology at Harvard Medical School.

The Wistar Institute is an international leader in biomedical research with special expertise in cancer research and vaccine development. Founded in 1892 as the first independent nonprofit biomedical research institute in the country, Wistar has long held the prestigious Cancer Center designation from the National Cancer Institute. The Institute works actively to ensure that research advances move from the laboratory to the clinic as quickly as possible. The Wistar Institute: Today's Discoveries - Tomorrow's Cures. On the Web at http://www.wistar.org

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2014-12-11

The saga of the Osedax "bone-eating" worms began 12 years ago, with the first discovery of these deep-sea creatures that feast on the bones of dead animals. The Osedax story grew even stranger when researchers found that the large female worms contained harems of tiny dwarf males.

In a new study published in the Dec. 11 issue of Current Biology, marine biologist Greg Rouse at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego and his collaborators reported a new twist to the Osedax story, revealing an evolutionary oddity unlike any other in the animal kingdom. Rouse's ...

2014-12-11

HOUSTON -- (Dec. 11, 2014) -- In a triumph for cell biology, researchers have assembled the first high-resolution, 3-D maps of entire folded genomes and found a structural basis for gene regulation -- a kind of "genomic origami" that allows the same genome to produce different types of cells. The research appears online today in Cell.

A central goal of the five-year project, which was carried out at Baylor College of Medicine, Rice University, the Broad Institute and Harvard University, was to identify the loops in the human genome. Loops form when two bits of DNA that ...

2014-12-11

BUFFALO, N.Y. -- Some drugs used to treat diabetes mimic the behavior of a hormone that a University at Buffalo psychologist has learned controls fluid intake in subjects. The finding creates new awareness for diabetics who, by the nature of their disease, are already at risk for dehydration.

Derek Daniels' paper "Endogenous Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Reduces Drinking Behavior and Is Differentially Engaged by Water and Food Intakes in Rats," co-authored with UB psychology graduate students Naomi J. McKay and Daniela L. Galante, appears in this month's edition of the Journal ...

2014-12-11

London, United Kingdom, December 11, 2014 - Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) is an emerging virus, with the first case reported in 2012. It exhibits a 40% fatality rate and over 97% of the cases have occurred in the Middle East. In three new studies in the current issue of the International Journal of Infectious Disease, researchers reported on clinical outcomes in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), how long patients will shed virus during their infections, and how the Sultanate of Oman is dealing with cases that have appeared there. An editorial ...

2014-12-11

(MEMPHIS, Tenn. - December 11, 2014) Toddlers who undergo total body irradiation in preparation for bone marrow transplantation are at higher risk for a decline in IQ and may be candidates for stepped up interventions to preserve intellectual functioning, St. Jude Children's Research Hospital investigators reported. The findings appear in the current issue of the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The results clarify the risk of intellectual decline faced by children, teenagers and young adults following bone marrow transplantation. The procedure is used for treatment of cancer ...

2014-12-11

University of Rochester researchers believe they're on track to solve the mystery of weight gain - and it has nothing to do with indulging in holiday eggnog.

They discovered that a protein, Thy1, has a fundamental role in controlling whether a primitive cell decides to become a fat cell, making Thy1 a possible therapeutic target, according to a study published online this month by the FASEB Journal.

The research brings a new, biological angle to a problem that's often viewed as behavioral, said lead author Richard P. Phipps, Ph.D. In fact, some diet pills consist of ...

2014-12-11

New Rochelle, NY, December 11, 2014--In cases of traumatic brain injury (TBI), predicting the likelihood of a cranial lesion and determining the need for head computed tomography (CT) can be aided by measuring markers of bone injury in the blood. The results of a new study comparing the usefulness of two biomarkers released into the blood following a TBI are presented in Journal of Neurotrauma, a peer-reviewed journal from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers. The article is available free on the Journal of Neurotrauma website at http://online.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/neu.2013.3245 ...

2014-12-11

MAYWOOD, Il. - Riding a couple roller coasters at an amusement park appears to have triggered an unusual stroke in a 4-year-old boy, according to a report in the journal Pediatric Neurology.

The sudden acceleration, deceleration and rotational forces on the head and neck likely caused a tear in the boy's carotid artery. This tear, called a dissection, led to formation of a blood clot that triggered the stroke, Loyola University Medical Center neurologist Jose Biller, MD and colleagues report.

Strokes previously have been reported in adult roller coaster riders, but ...

2014-12-11

Worcester, Mass. - A new statistical model developed by a research team at Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) may enable physicians to create personalized cancer treatments for patients based on the specific genetic mutations found in their tumors.

Just as cancer is not a single disease, but a collection of many diseases, an individual tumor is not likely to be comprised of just one type of cancer cell. In fact, the genetic mutations that lead to cancer in the first place also often result in tumors with a mix of cancer cell subtypes.

The WPI team developed a new ...

2014-12-11

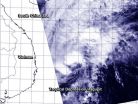

The once mighty super typhoon has weakened to a depression in the South China Sea as it heads for a final landfall in southern Vietnam. NASA's Aqua satellite captured an image of the storm that showed it was weakening.

NASA's Aqua satellite passed over Hagupit on Dec. 11 at 05:20 UTC (12:20 a.m. EST) and the MODIS instrument captured a visible image of the storm. The MODIS image showed that the thunderstorms had become fragmented around the circulation center.

On Dec. 11 at 1500 UTC (10 a.m. EST) Tropical Depression Hagupit's maximum sustained winds dropped to 30 knots ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Herpes virus rearranges telomeres to improve viral replication

Findings lead to better understanding of how viruses replicate and role of telomeres in stopping viruses