(Press-News.org) A new study led by researchers at University of California, San Diego School of Medicine finds that the brains of obese children literally light up differently when tasting sugar.

Published online in International Journal of Obesity, the study does not show a causal relationship between sugar hypersensitivity and overeating but it does support the idea that the growing number of America's obese youth may have a heightened psychological reward response to food.

This elevated sense of "food reward" - which involves being motivated by food and deriving a good feeling from it - could mean some children have brain circuitries that predispose them to crave more sugar throughout life.

"The take-home message is that obese children, compared to healthy weight children, have enhanced responses in their brain to sugar," said first author Kerri Boutelle, PhD, professor in the Department of Psychiatry and founder of the university's Center for Health Eating and Activity Research (CHEAR).

"That we can detect these brain differences in children as young as eight years old is the most remarkable and clinically significant part of the study," she said.

For the study, the UC San Diego team scanned the brains of 23 children, ranging in age from 8 to 12, while they tasted one-fifth of a teaspoon of water mixed with sucrose (table sugar). The children were directed to swirl the sugar-water mix in the mouth with their eyes closed, while focusing on its taste.

Ten of the children were obese and 13 had healthy weights, as classified by their body mass indices. All had been pre-screened for factors that could confound the results. For example, they were all right-handed and none suffered from psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety or ADHD. They also all liked the taste of sucrose.

The brain images showed that obese children had heightened activity in the insular cortex and amygdala, regions of the brain involved in perception, emotion, awareness, taste, motivation and reward.

Notably, the obese children did not show any heightened neuronal activity in a third area of the brain - the striatum - that is also part of the response-reward circuitry and whose activity has, in other studies, been associated with obesity in adults.

The striatum, however, does not develop fully until adolescence. The researchers said one of the interesting aspects of the study is that the brain scans may be documenting, for the first time, the early development of the food reward circuitry in pre-adolescents.

"Any obesity expert will tell you that losing weight is hard and that the battle has to be won on the prevention side," said Boutelle, who is also a clinical psychologist. "The study is a wake-up call that prevention has to start very early because some children may be born with a hypersensitivity to food rewards or they may be able to learn a relationship between food and feeling better faster than other children."

According to studies, children who are obese have an 80 to 90 percent chance of growing up to become obese adults. Currently about one in three children in the U.S. is overweight or obese.

INFORMATION:

To learn more CHEAR and its weight management programs for children, call 855-827-3498 or email chear@ucsd.edu.

Co-authors include Christina Wierenga, UC San Diego and Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System; Amanda Bischoff-Grethe, Andrew James Melrose and Emily Grenesko-Stevens, UC San Diego; and Martin Paulus, Laureate Institute for Brain Research, Tulsa, OK.

Funding for the study was provided, in part, by National Institutes of Health (grants R01DK094475, R01 DK075861, K02HL112042, MH046001, MH042984, MH066122, MH001894 and MH092793).

PORTLAND, Ore. -- A large international group of scientists, including an Oregon Health & Science University neuroscientist, is publishing this week the results of a first-ever look at the genome of dozens of common birds. The scientists' research tells the story of how modern birds evolved after the mass extinction that wiped out dinosaurs and almost everything else on Earth 66 million years ago, and gives new details on how birds came to have feathers, flight and song.

The consortium of more than 200 scientists is publishing its findings nearly simultaneously this week ...

A team of researchers led by North Carolina State University has found that stacking materials that are only one atom thick can create semiconductor junctions that transfer charge efficiently, regardless of whether the crystalline structure of the materials is mismatched - lowering the manufacturing cost for a wide variety of semiconductor devices such as solar cells, lasers and LEDs.

"This work demonstrates that by stacking multiple two-dimensional (2-D) materials in random ways we can create semiconductor junctions that are as functional as those with perfect alignment" ...

Agricultural decisions made by our ancestors more than 10,000 years ago could hold the key to food security in the future, according to new research by the University of Sheffield.

Scientists, looking at why the first arable farmers chose to domesticate some cereal crops and not others, studied those that originated in the Fertile Crescent, an arc of land in western Asia from the Mediterranean Sea to the Persian Gulf.

They grew wild versions of what are now staple foods like wheat and barley along with other grasses from the region to identify the traits that make some ...

GAINESVILLE, Fla. --- Nature abhors a vacuum, which may explain the findings of a new study showing that bird evolution exploded 65 million years ago when nearly everything else on earth -- dinosaurs included -- died out.

The study is part of an ambitious project, published in today's issue of the journal Science, in which hundreds of scientists worldwide have decoded the avian genome.

Edward Braun, an evolutionary geneticist at the University of Florida and the UF Genetics Institute, is one of the key scientists who took part in this multi-year project that used nine ...

(Santa Barbara, Calif.) -- With more and more rainforest giving way to pasture and grazing land every year, the practice of cattle ranching in the Amazon has serious implications on a global scale. At the same time, however, it provides a degree of socioeconomic flexibility for Amazonian smallholders who simply can't survive on what the forest or agriculture provide.

In a paper published in the current issue of the journal Human Organization, UC Santa Barbara anthropologist Jeffrey Hoelle takes a look at the rise of cattle ranching in the Brazilian state of Acre and the ...

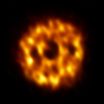

Astronomers using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) may have detected the dusty hallmarks of an entire family of Pluto-size objects swarming around an adolescent version of our own Sun.

By making detailed observations of the protoplanetary disk surrounding the star known as HD 107146, the astronomers detected an unexpected increase in the concentration of millimeter-size dust grains in the disk's outer reaches. This surprising increase, which begins remarkably far -- about 13 billion kilometers -- from the host star, may be the result of Pluto-size ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - If dieting is on your New Year agenda, it might pay to be mindful of a study suggesting there is little hard evidence that mindfulness leads to weight loss.

Ohio State University researchers reviewed 19 previous studies on the effectiveness of mindfulness-based programs for weight loss. Thirteen of the studies documented weight loss among participants who practiced mindfulness, but all lacked either a measure of the change in mindfulness or a statistical analysis of the relationship between being mindful and dropping pounds. In many cases, the studies ...

BOSTON (December 11, 2014) -- A new study from epidemiologists at Tufts University School of Medicine helps to identify communities with the greatest public health need in Massachusetts for resources relating to HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C. The study, published today in PLOS ONE, used geospatial techniques to identify hotspots for deaths related to HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C. The findings show large disparities in death rates exist across race and ethnicity in Massachusetts.

The HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C epidemics are challenging public health officials and clinicians in the ...

BALTIMORE, December 11, 2014 - Insilico Medicine along with scientists from Vision Genomics and Howard University shed light on AMD disease, introducing the opportunity for eventual diagnostic and treatment options.

The scientific collaboration between Vision Genomics, Inc., Howard University, and Insilico Medicine, Inc., has revealed encouraging insight on the AMD disease using an interactome analysis approach. Resources such as publicly available gene expression data, Insilico Medicine's original algorithm OncoFinderTM, and AMD MedicineTM from Vision Genomics allowed ...

How much protection the annual flu shot provides depends on how well the vaccine (which is designed based on a "best guess" for next season's flu strain) matches the actually circulating virus. However, it also depends on the strength of the immune response elicited by the vaccine. A study published on December 11th in PLOS Pathogens reports that genetic variants in a gene called IL-28B influence influenza vaccine responses.

Adrian Egli, from the University of Basel, Switzerland, and colleagues started with blood samples from organ transplant patients. Such patients are ...