(Press-News.org) A team of biologists has identified a set of nerve cells in desert locusts that bring about 'gang-like' gregarious behaviour when they are forced into a crowd.

Dr Swidbert Ott from the University of Leicester's Department of Biology, working with Dr Steve Rogers at the University of Sydney, Australia, has published a study that reveals how newly identified nerve cells in locusts produce the neurochemical serotonin to initiate changes in their behaviour and lifestyle.

The findings demonstrate the importance of individual history for understanding how brain chemicals control behaviour, which may apply more broadly to humans also.

Locusts are normally shy, solitary animals that actively avoid the company of other locusts. But when they are forced into contact with other locusts, they undergo a radical change in behaviour - they enter a 'bolder' gregarious state where they are attracted to the company of other locusts. This is the critical first step towards the formation of the notorious locust swarms.

Dr Ott said: "Locusts only have a small number of nerve cells that can synthesise serotonin. Now we have found that of these, a very select few respond specifically when a locust is first forced to be with other locusts. Within an hour, they produce more serotonin.

"It is these few cells that we think are responsible for the transformation of a loner into a gang member. In the long run, however, many of the other serotonin-cells also change, albeit towards making less serotonin."

When a locust is first forced into contact with other locusts, a specific set of nerve cells that produce the neurochemical serotonin is responsible for reconfiguring its behaviour so that the previously solitary locust becomes a member of the gang, which is known as 'gregarious' behaviour.

An entirely different set of its serotonin-producing nerve cells is then affected by life in the group in the long run.

Dr Ott added: "The key to our success was to look in locusts that have just become gregarious and that had never met another locust until an hour earlier. If we had looked only in solitary locusts and in locusts that had a life-long history of living in crowds, we would have missed the nerve cells that are the key players in the transformation.

"There is an important lesson here for understanding the mechanisms that drive changes in social behaviour in general, both in locusts and in humans. We have shown how important it is to look at what happens when a new social behaviour is first set up, not just at the long-term outcome.

"Research in insects can give us deep insights into how brains work in general, including our own."

Studies have previously shown that the change from solitary to gregarious behaviour is caused by serotonin.

The new study, which was funded by the Leverhulme Trust, the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) and the Royal Society, has identified the individual serotonin-producing nerve cells that are responsible for the switch from solitary to gregarious behaviour.

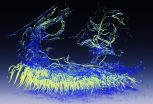

The scientists used a fluorescent stain that reveals the serotonin-producing nerve cells under the microscope. This allowed them to measure the amount of serotonin in individual nerve cells -- the brighter a nerve cell lights up, the more serotonin it contains. The newly identified cells were much brighter in locusts that had just been forcedly crowded with other locusts. Moreover, the same cells were also brighter in locusts that had their hind legs tickled by the researchers for an hour -- which is sufficient to make the locusts behave gregariously.

Serotonin has important roles in the brains of all animals that include the regulation of moods and social interactions.

In humans, there are strong links between changes in serotonin and mental disorders such as depression and anxiety.

Study shows 'swarm' mentality in locusts is a result of specific nerve cells that produce the brain chemical serotonin

Serotonin in humans is known to affect mood and behaviour such as aggression and anxiety

Research in insects can give us deep insights into how brains work in general, including the human brain

INFORMATION:

An image of nerve cells in a desert locust available to download at: https://www.dropbox.com/sh/xqzj5dgg97txkpt/AAD6mE3544Z5z79i_dsDuMuUa?dl=0

The paper, 'Differential activation of serotonergic neurons during short- and long-term gregarization of desert locusts', published in the academic journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, can be found here: http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/282/1800/20142062 DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2014.2062

Messier 47 is located approximately 1600 light-years from Earth, in the constellation of Puppis (the poop deck of the mythological ship Argo). It was first noticed some time before 1654 by Italian astronomer Giovanni Battista Hodierna and was later independently discovered by Charles Messier himself, who apparently had no knowledge of Hodierna's earlier observation.

Although it is bright and easy to see, Messier 47 is one of the least densely populated open clusters. Only around 50 stars are visible in a region about 12 light-years across, compared to other similar objects ...

Treating bacterial infections with antibiotics is becoming increasingly difficult as bacteria develop resistance not only to the antibiotics being used against them, but also to ones they have never encountered before. By analyzing genetic and phenotypic changes in antibiotic-resistant strains of E. coli, researchers at the RIKEN Quantitative Biology Center (QBiC) in Japan have revealed a common set of features that appear to be responsible for the development of resistance to several types of antibiotics.

The study published in Nature Communications shows that resistance ...

Fireflies used rapid light flashes to communicate. This "bioluminescence" is an intriguing phenomenon that has many potential applications, from drug testing and monitoring water contamination, and even lighting up streets using glow-in-dark trees and plants. Fireflies emit light when a compound called luciferin breaks down. We know that this reaction needs oxygen, but what we don't know is how fireflies actually supply oxygen to their light-emitting cells. Using state-of-the-art imaging techniques, scientists from Switzerland and Taiwan have determined how fireflies control ...

This news release is available in French. This news release is available in French.

People with a severe mental disorder who commit a crime and who are incarcerated have different characteristics compared to people who are hospitalized after committing an offence. These are the findings of a study by researchers at the Institut universitaire en santé mentale de Montréal (IUSMM) and the Institut Philippe-Pinel de Montréal (IPPM), affiliated with the University of Montreal.

"We found a clear difference between people with a mental illness who are ...

Cancer Research UK scientists have shown that loss of a gene called PTEN triggers some cases of an aggressive form of ovarian cancer, called high-grade serous ovarian cancer, according to a study published in Genome Biology today (Wednesday)*.

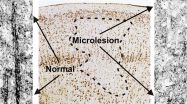

In a revolutionary approach the researchers from the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute made the discovery by combining images from cancer samples with genetic data. They proved conclusively that loss of PTEN was commonly found only in the cancerous cells and not the 'normal' cells that help make up the tumour mass.

PTEN ...

Using an innovative technique combining genetic analysis and mathematical modeling with some basic sleuthing, researchers have identified previously undescribed microlesions in brain tissue from epileptic patients. The millimeter-sized abnormalities may explain why areas of the brain that appear normal can produce severe seizures in many children and adults with epilepsy.

The findings, by researchers at the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Medicine, Wayne State University and Montana State University, are reported in the journal Brain.

Epilepsy affects about ...

The deep sea is becoming a collecting ground for plastic waste, according to research led by scientists from Plymouth University and Natural History Museum.

The new study, published today in Royal Society Open Science, reveals around four billion microscopic plastic fibres could be littering each square kilometre of deep sea sediment around the world.

Marine plastic debris is a global problem, affecting wildlife, tourism and shipping. Yet monitoring over the past decades has not seen its concentration increase at the sea surface or along shorelines, despite experts ...

New research suggests our jawed ancestors weren't responsible for the demise of their jawless cousins as had been assumed. Instead Dr Robert Sansom from The University of Manchester believes rising sea levels are more likely to blame. His research has been published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

He says: "When our jawed vertebrate ancestors overtook their jawless relatives 400 million years ago, it seems that it might not have been through direct competition but instead the inability of our jawless cousins to adapt to changing environmental conditions."

In ...

In another demonstration that brain-computer interface technology has the potential to improve the function and quality of life of those unable to use their own arms, a woman with quadriplegia shaped the almost human hand of a robot arm with just her thoughts to pick up big and small boxes, a ball, an oddly shaped rock, and fat and skinny tubes.

The findings by researchers at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, published online today in the Journal of Neural Engineering, describe, for the first time, 10-degree brain control of a prosthetic device in which ...

NEW YORK (16 December 2014) -- The Population Council published new research in the November issue of the journal Contraception demonstrating that an investigational one-year contraceptive vaginal ring containing Nestorone® and ethinyl estradiol was found to be highly acceptable among women enrolled in a Phase 3 clinical trial. Because the perspectives of women are critical for defining acceptability, researchers developed a theoretical model based on women's actual experiences with this contraceptive vaginal ring, and assessed their overall satisfaction and adherence ...