(Press-News.org) A close look at the night sky reveals that stars don't like to be alone; instead, they congregate in clusters, in some cases containing as many as several million stars. Until recently, the oldest of these populous star clusters were considered well understood, with the stars in a single group having formed at different times, over periods of more than 300 million years. Yet new research published online today in the journal Nature suggests that the star formation in these clusters is more complex.

Using data from the Hubble Space Telescope, a team of researchers at the Kavli Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics (KIAA) at Peking University and the Chinese Academy of Science's National Astronomical Observatories in Beijing have found that, in large middle-aged clusters at least, all stars appear to be of about the same age.

Stars begin their lives as billowing clouds of dust and gas. Pulled together by gravity, these clouds slowly coalesce into dense spheres that, if they grow large enough, heat up and begin to convert hydrogen into helium in their cores. This process releases energy and makes them shine. Billions of years later, when they reach the end of their core hydrogen supply, the stars begin to burn hydrogen in a shell around their cores and, as a result, their temperature changes.

Previous observations of massive star clusters revealed a relatively large amount of variation in temperature from stars reaching the end of their core hydrogen supply, suggesting that the stars within the clusters varied in age by as much as 300 million years or more.

"This has long been surprising," said Chengyuan Li, a doctoral student at Peking University and the lead author of the new study. "Young clusters are thought to quickly lose any remaining star-forming gas during the first 10 million years of their lifetimes," which would make it difficult for the stars in a single cluster to vary in age by more than about 10 million years.

Observing a middle-aged, 2 billion-year-old star cluster located in the Large Magellanic Cloud called NGC 1651, the researchers looked for both the change in temperature that occurs when stars reach the end of their hydrogen supply - which is what previous studies had focused on - and a second change in temperature that occurs as the stars burn hydrogen in a shell around their core.

While they found the expected wide variation in temperature of stars finishing their core hydrogen reserves, the astronomers were surprised to find very little variation when looking at the brightnesses of stars of similar temperatures burning hydrogen in the shell outside the core. The lack of variation among these stars led the researchers to conclude that the stars in this cluster must all be within just 80 million years of the same age - a very small age range for such an old cluster.

"NGC 1651 is the best example found to date of a truly single-age stellar population," said Richard de Grijs, a faculty member at KIAA involved in the study. "We have since identified a handful of other middle-aged clusters that appear to show similar features."

The research suggests that, for middle-aged clusters at least, today's conventional wisdom may be wrong and it might be common for all stars in a single cluster to be of approximately the same age.

A decade ago, astronomers actually thought that the stars within any cluster should all be about the same age, but that idea fell out of favor when clear evidence of the presence of stars of different ages within a single cluster was discovered, at least for the oldest and most populous clusters in our Milky Way. Based on today's Nature paper, a reverse shift looks necessary.

In addition to that important realization, the paper's authors suggest that the wide range of brightness seen in stars reaching the end of their core hydrogen supply may actually be due to stellar rotation. That's because two stars of exactly the same age can exhibit different levels of observed temperature if they rotate at significantly different rates.

Most current models don't take stellar rotation into account, de Grijs said. Future studies may offer even greater insight into the age of star clusters by better modeling stellar rotation rates and using those models to interpreting the variation in temperature of stars burning the last of their core hydrogen, he said.

Licai Deng, principal scientist at the National Astronomical Observatories, said, "these latest results resolve nearly a decade of debate among scientists; as such, the results were deemed 'solid and welcome' by the peer-reviewers."

INFORMATION:

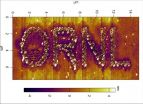

OAK RIDGE, Tenn., Dec. 17, 2014--Scientists at the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory have used advanced microscopy to carve out nanoscale designs on the surface of a new class of ionic polymer materials for the first time. The study provides new evidence that atomic force microscopy, or AFM, could be used to precisely fabricate materials needed for increasingly smaller devices.

Polymerized ionic liquids have potential applications in technologies such as lithium batteries, transistors and solar cells because of their high ionic conductivity and unique ...

UCLA researchers have developed a lens-free microscope that can be used to detect the presence of cancer or other cell-level abnormalities with the same accuracy as larger and more expensive optical microscopes.

The invention could lead to less expensive and more portable technology for performing common examinations of tissue, blood and other biomedical specimens. It may prove especially useful in remote areas and in cases where large numbers of samples need to be examined quickly.

The microscope is the latest in a series of computational imaging and diagnostic devices ...

VIDEO:

It's official -- our holiday lights are so bright we can see them from space. Thanks to the VIIRS instrument on the Suomi NPP satellite, a joint mission between NASA...

Click here for more information.

Even from space, holidays shine bright.

With a new look at daily data from the NOAA/NASA Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership (Suomi NPP) satellite, a NASA scientist and colleagues have identified how patterns in nighttime light intensity change during major holiday ...

The sun emitted a mid-level solar flare, peaking at 11:50 p.m. EST on Dec. 16, 2014. NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory, which watches the sun constantly, captured an image of the event. Solar flares are powerful bursts of radiation. Harmful radiation from a flare cannot pass through Earth's atmosphere to physically affect humans on the ground, however -- when intense enough -- they can disturb the atmosphere in the layer where GPS and communications signals travel.

To see how this event may affect Earth, please visit NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center at http://spaceweather.gov, ...

In the first real-world trial of the impact of patient-controlled access to electronic medical records, almost half of the patients who participated withheld clinically sensitive information in their medical records from some or all of their health care providers.

This is the key finding of a new study by researchers from Clemson University, the Regenstrief Institute, Indiana University School of Medicine and Eskenazi Health published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.

Kelly Caine, assistant professor in Clemson's School of Computing, and colleagues at Clemson ...

A team of scientists, led by the University of Toronto's Barbara Sherwood Lollar, has mapped the location of hydrogen-rich waters found trapped kilometres beneath Earth's surface in rock fractures in Canada, South Africa and Scandinavia.

Common in Precambrian Shield rocks - the oldest rocks on Earth - the ancient waters have a chemistry similar to that found near deep sea vents, suggesting these waters can support microbes living in isolation from the surface.

The study, to be published in Nature on December 18, includes data from 19 different mine sites that were ...

Chemical modifications to DNA's packaging -- known as epigenetic changes -- can activate or repress genes involved in autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) and early brain development, according to a new study to be published in the journal Nature on Dec. 18.

Biochemists from NYU Langone Medical Center found that these epigenetic changes in mice and laboratory experiments remove the blocking mechanism of a protein complex long known for gene suppression, and transitions the complex to a gene activating role instead.

Researchers say their findings represent the first link ...

LA JOLLA, CA--December 17, 2014--Chemists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have invented a powerful method for joining complex organic molecules that is extraordinarily robust and can be used to make pharmaceuticals, fabrics, dyes, plastics and other materials previously inaccessible to chemists.

"We are rewriting the rules for how one thinks about the reactivity of basic organic building blocks, and in doing so we're allowing chemists to venture where none has gone before," said Phil S. Baran, the Darlene Shiley Chair in Chemistry at TSRI, whose laboratory reports ...

Johns Hopkins and University of Alberta researchers have identified a single protein as the root of painful and dangerous allergic reactions to a range of medications and other substances. If a new drug can be found that targets the problematic protein, they say, it could help smooth treatment for patients with conditions ranging from prostate cancer to diabetes to HIV. Their results appear in the journal Nature on Dec. 17.

Previous studies traced reactions such as pain, itching and rashes at the injection sites of many drugs to part of the immune system known as mast ...

Researchers found 53 existing drugs that may keep the Ebola virus from entering human cells, a key step in the process of infection, according to a study led by researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and published today in the Nature Press journal Emerging Microbes and Infections.

Among the better known drug types shown to hinder infection by an Ebola virus model: several cancer drugs, antihistamines and antibiotics. Among the most effective at keeping the virus out of human cells were microtubule inhibitors ...