(Press-News.org) Northwestern University scientists have developed a robust new material, inspired by biological catalysts, that is extraordinarily effective at destroying toxic nerve agents that are a threat around the globe. First used 100 years ago during World War I, deadly chemical weapons continue to be a challenge to combat.

The material, a zirconium-based metal-organic framework (MOF), degrades in minutes one of the most toxic chemical agents known to mankind: Soman (GD), a more toxic relative of sarin. Computer simulations show the MOF should be effective against other easy-to-make agents, such as VX.

The catalyst is fast and effective under a wide range of conditions, and the porous MOF structure can store a large amount of toxic gas as the catalyst does its work. These features make the material promising for use in protective equipment worn by soldiers, such as gas masks, and for destroying stockpiles of chemical weapons, such as those currently building up in Syria.

"This designed material is very thermally and chemically robust, and it doesn't care what conditions it is in," said chemist Omar K. Farha, who led the research. "The material can be in water or a very humid environment, at a temperature of 130 degrees or minus 15, or in a dust storm. A soldier should not need to worry about under what conditions his protective mask will work. We can put this new catalyst in rugged conditions, and it will work just fine."

MOFs are very porous, so they can capture, store and destroy a lot of the nasty material, Farha said, making them very attractive for defense-related applications.

The study, the first to demonstrate zirconium MOFs as effective weapons against nerve agents, will be published March 16 by the journal Nature Materials.

"Simple changes to the nerve agent's molecular structure can change something that can kill a human into something harmless," said Farha, a research professor of chemistry in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences. "GD and VX are not very sophisticated agents, but they are very toxic. With the correct chemistry, we can render toxic materials nontoxic."

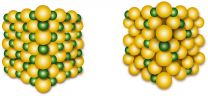

Metal-organic frameworks are well-ordered, lattice-like crystals. The nodes of the lattices are metals, and organic molecules connect the nodes. Within their very roomy pores, MOFs can effectively capture gases, such as nerve agents.

The Northwestern MOF, called NU-1000, has nodes of zirconium -- the active catalytic site where all the important chemistry takes place. The organic ligand gives the material its important structure by connecting the nodes, but it does not participate in the catalysis of the nerve agent.

The zirconium node selectively clips the phosphate-ester bond in the nerve agent, rendering it innocuous. With the critical bond broken, the rest of the molecule is left alone. The bond is broken through the process of hydrolysis, a reaction involving the breaking of a molecule's bond using water. The MOF can use the humidity in the air.

In their study, the researchers first tested their catalyst against a GD simulant, called DMNP, and found the MOF degraded half of the target in less than 1.5 minutes. Next, they tested the MOF against GD and found the catalyst degraded half of the nerve agent in less than three minutes. These half-lives are very impressive, Farha said, and show how well the catalyst is working.

They also tested the zirconium cluster alone, without the cluster being in the MOF structure, and the catalyst was not as effective at degrading the nerve agent. This shows the importance of the MOF scaffold.

The research team's experimental and computational results suggest that the extraordinary activity of NU-1000 comes from the unique zirconium node and the MOF structure that allows the material to engage with more of the nerve agent and to destroy it. The researchers expect the MOF to be effective against other easy-to-make chemical warfare agents with phosphate-ester bonds, such as VX.

NU-1000 is inspired by the enzyme phosphotriesterase, which is found in bacteria. The natural enzyme has two zinc ions bridged by a hydroxyl group as the active catalytic site. Farha and his colleagues wanted to make a much more potent and stable catalyst, so they used zirconium ions instead of zinc.

"We are learning from nature, but trying to do better by making more robust materials," Farha said. "The natural enzyme does precisely the same chemistry, but its lifetime is very short -- it cannot survive under the conditions soldiers are deployed in."

Even though the synthetic catalyst yields the same weapons-degradation product as the enzyme, it does so by a means that is much less dependent on the exact structure and composition of the chemical weapon target. The next step, therefore, is to determine the extent to which the artificial catalyst functions as a broad-spectrum catalyst.

Farha added, "Our catalyst is fantastic compared to other catalysts, but there is still more work to be done."

INFORMATION:

The paper is titled "Destruction of Chemical Warfare Agents Utilizing Metal-Organic Frameworks."

In addition to Farha, other authors of the paper are Joseph E. Mondloch (co-first author), Michael J. Katz (co-first author), Pritha Ghosh, Peilin Liao, Wojciech Bury, Randall Q. Snurr and Joseph T. Hupp, from Northwestern; William C. Isley III and Christopher J. Cramer, from the University of Minnesota; George W. Wagner, Morgan G. Hall and Gregory W. Peterson, from the U.S. Army Research, Development and Engineering Command; and Jared B. DeCoste, from Leidos, Inc.

"Warmer air transports more moisture and hence produces more precipitation - in cold Antarctica this takes the form of snowfall," lead author Katja Frieler from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) explains. "We have now pulled a number of various lines of evidence together and find a very consistent result: Temperature increase means more snowfall on Antarctica," says Frieler. "For every degree of regional warming, snowfall increases by about 5 percent." Published in the journal Nature Climate Change, the scientists' work builds on high-quality ice-core ...

Researchers have discovered a valley underneath East Antarctica's most rapidly-changing glacier that delivers warm water to the base of the ice, causing significant melting.

The intrusion of warm ocean water is accelerating melting and thinning of Totten Glacier, which at 65 kilometres long and 30 kilometres wide contains enough ice to raise global sea levels by 3.5 metres. The glacier is one of the major outlets for the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, which is the largest mass of ice on Earth and covers 98 percent of the continent.

Climate change is raising the temperature ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. - A new study confirms that snowfall in Antarctica will increase significantly as the planet warms, offsetting future sea level rise from other sources - but the effect will not be nearly as strong as many scientists previously anticipated because of other, physical processes.

That means that many computer models may be underestimating the amount and rate of sea level rise if they had projected more significant impact from Antarctic snow.

Results of the study, which was funded by the National Science Foundation, were reported this week in the journal ...

About one quarter of the global seafloor is extremely nutrient poor. Contrary to previous assumptions, it contains oxygen not just in the thin surface layer, but also throughout its entire thickness. The underlying basement rocks contain oxygen as well. An international research team made these new discoveries through analysis of drill cores from the South Pacific Gyre.

In the latest issue of Nature Geoscience the scientists also point out the potential effects on the composition of Earth's interior because oxygen-containing deep-sea sediment has a different mineral composition ...

The underlying mechanism behind an enigmatic process called "singlet exciton fission", which could enable the development of significantly more powerful solar cells, has been identified by scientists in a new study.

The process is only known to happen in certain materials, and occurs when they absorb light. As the light particles come into contact with electrons within the material, the electrons are excited by the light, and the resulting "excited state" splits into two.

If singlet exciton fission can be controlled and incorporated into solar cells, it has the potential ...

Climbing rats, seabirds and tropical gophers are among the 15 animal species that are at the absolute greatest risk of becoming extinct very soon. Expertise and money is needed to save them and other highly threatened species.

A new study shows that a subset of highly threatened species - in this case 841 - can be saved from extinction for about $1.3 billion a year. However, for 15 of them the chances of conservation success are really low.

The study published in Current Biology concludes that a subset of 841 endangered animal species can be saved, but only if conservation ...

New heart imaging technology to diagnose coronary heart disease and other heart disorders is significantly more accurate, less expensive and safer than traditional methods, according to a new study by researchers from the Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute in Salt Lake City.

Researchers at the Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute compared Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT), currently the most commonly used imaging diagnostic tool, with a new imaging technology -- coronary-specific Positron Emission Tomography (cardiac PET/CT).

They ...

Montreal, March 16, 2015 -- Does a predilection for porn mean bad news in bed? That's the conclusion of many clinicians and the upshot of anecdotal reports claiming a man's habit of viewing sex films can lead to problems getting or sustaining an erection.

But a new study from UCLA and Concordia University -- the first to actually test the relationship between how much erotica men are watching and erectile function -- shows that viewing sexual films is unlikely to cause erectile problems and may even help sexual arousal.

The study, published in the online journal Sexual ...

This news release is available in German.

The lithium ion battery currently is the most widespread battery technology. It is indispensable for devices, such as laptops, mobile phones or cameras. Current research activities are aimed at reaching higher lithium storage densities in order to increase the amount of energy stored in a battery. Moreover, lithium storage should be quick for energy supply of devices with high power requirements. This requires the detailed understanding of the electrochemical processes and new development of battery components.

The materials ...

SAN DIEGO (March 16, 2015) -- Despite the advent of a new generation of stents, patients with multiple narrowed arteries in the heart who received coronary artery bypass grafting fared better than those whose arteries were opened with balloon angioplasty and stents in a study presented at the American College of Cardiology's 64th Annual Scientific Session.

The findings echo past studies, which have shown patients with multiple narrowed arteries have better outcomes with coronary artery bypass grafting, also known as CABG or heart bypass surgery, than with angioplasty, ...