(Press-News.org) Scientists at the University of Cambridge have successfully created 'mini-lungs' using stem cells derived from skin cells of patients with cystic fibrosis, and have shown that these can be used to test potential new drugs for this debilitating lung disease.

The research is one of a number of studies that have used stem cells - the body's master cells - to grow 'organoids', 3D clusters of cells that mimic the behaviour and function of specific organs within the body. Other recent examples have been 'mini-brains' to study Alzheimer's disease and 'mini-livers' to model liver disease. Scientists use the technique to model how diseases occur and to screen for potential drugs; they are an alternative to the use of animals in research.

Cystic fibrosis is a monogenic condition - in other words, it is caused by a single genetic mutation in patients, though in some cases the mutation responsible may differ between patients. One of the main features of cystic fibrosis is the lungs become overwhelmed with thickened mucus causing difficulty breathing and increasing the incidence of respiratory infection. Although patients have a shorter than average lifespan, advances in treatment mean the outlook has improved significantly in recent years.

Researchers at the Wellcome Trust-Medical Research Council Cambridge Stem Cell Institute used skin cells from patients with the most common form of cystic fibrosis caused by a mutation in the CFTR gene referred to as the delta-F508 mutation. Approximately three in four cystic fibrosis patients in the UK have this particular mutation. They then reprogrammed the skin cells to an induced pluripotent state, the state at which the cells can develop into any type of cell within the body.

Using these cells - known as induced pluripotent stem cells, or iPS cells - the researchers were able to recreate embryonic lung development in the lab by activating a process known as gastrulation, in which the cells form distinct layers including the endoderm and then the foregut, from which the lung 'grows', and then pushed these cells further to develop into distal airway tissue. The distal airway is the part of the lung responsible for gas exchange and is often implicated in disease, such as cystic fibrosis, some forms of lung cancer and emphysema.

The results of the study are published in the journal Stem Cells and Development.

"In a sense, what we've created are 'mini-lungs'," explains Dr Nick Hannan, who led the study. "While they only represent the distal part of lung tissue, they are grown from human cells and so can be more reliable than using traditional animal models, such as mice. We can use them to learn more about key aspects of serious diseases - in our case, cystic fibrosis."

The genetic mutation delta-F508 causes the CFTR protein found in distal airway tissue to misfold and malfunction, meaning it is not appropriately expressed on the surface of the cell, where its purpose is to facilitate the movement of chloride in and out of the cells. This in turn reduces the movement of water to the inside of the lung; as a consequence, the mucus becomes particular thick and prone to bacterial infection, which over time leads to scarring - the 'fibrosis' in the disease's name.

Using a fluorescent dye that is sensitive to the presence of chloride, the researchers were able to see whether the 'mini-lungs' were functioning correctly. If they were, they would allow passage of the chloride and hence changes in fluorescence; malfunctioning cells from cystic fibrosis patients would not allow such passage and the fluorescence would not change. This technique allowed the researchers to show that the 'mini-lungs' could be used in principle to test potential new drugs: when a small molecule currently the subject of clinical trials was added to the cystic fibrosis 'mini lungs', the fluorescence changed - a sign that the cells were now functioning when compared to the same cells not treated with the small molecule.

"We're confident this process could be scaled up to enable us to screen tens of thousands of compounds and develop mini-lungs with other diseases such as lung cancer and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis," adds Dr Hannan. "This is far more practical, should provide more reliable data and is also more ethical than using large numbers of mice for such research."

INFORMATION:

The research was primarily funded by the European Research Council, the National Institute for Health Research Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre and the Evelyn Trust. END

Women who received a text message reminding them about their breast cancer screening appointment were 20 per cent more likely to attend than those who were not texted, according to a study published in the British Journal of Cancer today (Thursday)*.

Researchers, funded by the Imperial College Healthcare Charity, trialled text message reminders for women aged 47-53 years old who were invited for their first appointment for breast cancer screening.

The team compared around 450 women who were sent a text with 435 women who were not texted**. It found that 72 per cent ...

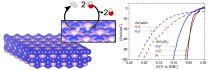

PISCATAWAY, N.J. (March 18, 2015) - New research published by Rutgers University chemists has documented significant progress confronting one of the main challenges inhibiting widespread utilization of sustainable power: Creating a cost-effective process to store energy so it can be used later.

"We have developed a compound, Ni5P4 (nickel-5 phosphide-4), that has the potential to replace platinum in two types of electrochemical cells: electrolyzers that make hydrogen by splitting water through hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) powered by electrical energy, and fuel cells ...

The number of people living with cystic fibrosis into adulthood in the UK is expected to increase dramatically - by as much as 80 per cent - by 2025, according to a Europe-wide survey, the UK end of which was led by Queen's University Belfast.

People living with cystic fibrosis have previously had low life expectancy, but improvements in treatments in the last three decades have led to an increase in survival with almost all children now living to around 40 years. In countries where reliable data exists, the average rise in the number of adults with CF is expected to be ...

A recent study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry reports that following military parents' return from combat deployment, their children show increased visits for mental healthcare, physical injury, and child maltreatment consults, compared to children whose parents have not been deployed. The same types of healthcare visits were also found to be significantly higher for children of combat-injured parents.

Children of deployed parents are known to have increased mental healthcare needs, and be at increased risk for child ...

When cancer strikes, it may be possible for patients to fight back with their own defenses, using a strategy known as immunotherapy. According to a new study published in Nature, researchers have found a way to enhance the effects of this therapeutic approach in glioblastoma, a deadly type of brain cancer, and possibly improve patient outcomes. The research was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) as well as the National Cancer Institute (NCI), which are part of the National Institutes of Health.

"The promise of dendritic cell-based ...

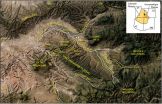

Boulder, Colo., USA - Unaweep Canyon is a puzzling landscape -- the only canyon on Earth with two mouths. First formally documented by western explorers mapping the Colorado Territory in the 1800s, Unaweep Canyon has inspired numerous hypotheses for its origin. This new paper for Geosphere by Gerilyn S. Soreghan and colleagues brings together old and new geologic data of this region to further the hypothesis that Unaweep Canyon was formed in multiple stages.

The inner gorge originated ~300 million years ago, was buried, was then revealed about five million years ago when ...

Latinos are the largest ethnic minority group in the United States, and it's expected that by 2050 they will comprise almost 30 percent of the U.S. population. Yet they are also the most underserved by health care and health insurance providers.

Latinos' low rates of insurance coverage and poor access to health care strongly suggest a need for better outreach by health care providers and an improvement in insurance coverage. Although the implementation of the Affordable Care Act of 2010 seems to have helped (approximately 25 percent of those eligible for coverage under ...

Could our reaction to an image of an overweight or obese person affect how we perceive odor? A trio of researchers, including two from UCLA, says yes.

The researchers discovered that visual cues associated with overweight or obese people can influence one's sense of smell, and that the perceiver's body mass index matters, too. Participants with higher BMI tended to be more critical of heavier people, with higher-BMI participants giving scents a lower rating when scent samples were matched with an obese or overweight individual.

The findings, published online in the ...

COLLEGE STATION -- Researchers at Texas A&M AgriLife Research have developed a new technology to determine sensitivity or resistance to rabies virus.

"We were able to create a novel platform such that we could look at how pathogens, such as bacteria or virus or even drugs or radiation, interact with specific human genes," said lead researcher Dr. Deeann Wallis, AgriLife Research assistant professor of biochemistry and biophysics. "It allows us a new way to profile the genes involved in sensitivity or resistance to certain agents."

The rabies work is being reported in ...

SAVANNAH, Ga., March 19, 2015 - Bad news for relentless power-seekers the likes of Frank Underwood on House of Cards: Climbing the ladder of social status through aggressive, competitive striving might shorten your life as a result of increased vulnerability to cardiovascular disease. That's according to new research by psychologist Timothy W. Smith and colleagues at the University of Utah. And good news for successful types who are friendlier: Attaining higher social status as the result of prestige and freely given respect may have protective effects, the researchers ...