(Press-News.org) March 19, 2015--(Bronx, NY)--Scientists at Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University and their international collaborators have developed a novel fluorescence microscopy technique that for the first time shows where and when proteins are produced. The technique allows researchers to directly observe individual messenger RNA molecules (mRNAs) as they are translated into proteins in living cells. The technique, carried out in living human cells and fruit flies, should help reveal how irregularities in protein synthesis contribute to developmental abnormalities and human disease processes including those involved in Alzheimer's disease and other memory-related disorders. The research will be published the March 20 edition of Science.

"We've never been able to pinpoint exactly when and where mRNAs are translated into proteins," said study co-leader Robert H. Singer, Ph.D., professor and co-chair of anatomy and structural biology and co-director of the Gruss Lipper Biophotonics Center at Einstein. "This capability will be critical for studying the molecular basis of disease, for example, how dysregulation of protein synthesis in brain cells can lead to the memory deficits that occur in neurodegeneration." Dr. Singer also holds the Harold and Muriel Block Chair in Anatomy & Structural Biology at Einstein.

The directions for making proteins are encoded in genes in the cell nucleus. Two steps--transcription and translation--must occur so that the gene's protein-making instructions will lead to actual proteins. In the first step, called transcription, the gene's DNA is "read" by molecules of mRNA. These mRNAs then migrate from the nucleus into the cytoplasm and attach to structures called ribosomes. That's where translation, the second step in protein synthesis, occurs: the mRNAs attached to ribosomes function as templates on which proteins are constructed.

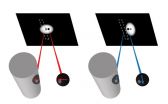

To visualize translation, Dr. Singer and his colleagues took advantage of a key occurrence during the first round of translation: the ribosome to which mRNAs attach must displace so-called RNA-binding proteins from the mRNAs. The researchers synthesized identical copies of mRNA molecules containing two fluorescent proteins, one green and one red. This meant that in the nucleus (where mRNAs are made), mRNAs labeled with both red and green proteins appear yellow. After migrating to the cytoplasm, the mRNAs can change color depending on their fate.

For mRNAs landing on ribosomes, the ribosome displaces the mRNAs' green fluorescent protein. As a result, these mRNA molecules--stripped of their green fluorescent proteins, bound to ribosomes, and ready to be translated into a protein--appear red. Meanwhile, all the untranslated mRNA molecules remain yellow. The technique was dubbed TRICK (for Translating RNA Imaging by Coat protein Knock-off).

In a test of TRICK, the collaborators in Germany studied when and where mRNAs for a gene called oskar are expressed in Drosophila eggs, or oocytes. (Drosophila, or fruit flies, are a frequently used model for understanding human disease, and oskar is critical for normal development of fruit fly embryos.) The researchers made oskar mRNAs tagged with red and green fluorescent proteins and inserted the tagged mRNAs into the nuclei of Drosophila oocytes.

"Using TRICK, oskar mRNAs were not translated until they reached the posterior pole of the oocyte," said Dr .Singer. "We suspected this, but now we have definitive proof. Going forward, researchers can use this technique to dissect the cascade of regulatory events required for mRNA translation during Drosophila development."

The researchers also found that protein translation doesn't start immediately after mRNAs exit the nucleus but instead gets underway several minutes after mRNAs have entered the cytoplasm. "We never knew that timeframe before," said Dr. Singer. "That's another example of what we can learn using this technique."

INFORMATION:

The paper is titled "An RNA biosensor for imaging the first round of translation from single cells to living animals." The other contributors are: Timothée Lionnet, Ph.D., now at Janelia research Campus of the HHMI; James M. Halstead, Ph.D., and Jeffrey A. Chao, Ph.D., at Friedrich Miescher Institute for Biomedical Research, Basel, Switzerland; Johannes H. Wilbertz, Ph.D. student, at Friedrich Miescher Institute for Biomedical Research and University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland; Frank Wippich, Ph.D., and Anne Ephrussi, Ph.D., at European Molecular Biology Laboratory, Heidelberg, Germany.

This study was supported by grants from the Novartis Research Foundation, National Institutes of Health (NS83085, EB13571 and GM57071), Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and European Molecular Biology Laboratory.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

About Albert Einstein College of Medicine

Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University is one of the nation's premier centers for research, medical education and clinical investigation. During the 2013-2014 academic year, Einstein is home to 743 M.D. students, 275 Ph.D. students, 103 students in the combined M.D./Ph.D. program, and 313 postdoctoral research fellows. The College of Medicine has more than 2,000 full-time faculty members located on the main campus and at its clinical affiliates. In 2013, Einstein received more than $150 million in awards from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This includes the funding of major research centers at Einstein in aging, intellectual development disorders, diabetes, cancer, clinical and translational research, liver disease, and AIDS. Other areas where the College of Medicine is concentrating its efforts include developmental brain research, neuroscience, cardiac disease, and initiatives to reduce and eliminate ethnic and racial health disparities. Its partnership with Montefiore Medical Center, the University Hospital and academic medical center for Einstein, advances clinical and translational research to accelerate the pace at which new discoveries become the treatments and therapies that benefit patients. Through its extensive affiliation network involving Montefiore, Jacobi Medical Center -- Einstein's founding hospital, and three other hospital systems in the Bronx, Brooklyn and on Long Island, Einstein runs one of the largest residency and fellowship training programs in the medical and dental professions in the United States. For more information, please visit www.einstein.yu.edu, read our blog, follow us on Twitter, like us on Facebook, and view us on YouTube. END

Prosthetics with a realistic sense of touch. Bridges that detect and repair their own damage. Vehicles with camouflaging capabilities.

Advances in materials science, distributed algorithms and manufacturing processes are bringing all of these things closer to reality every day, says a review published today in the journal Science by Nikolaus Correll, assistant professor of computer science, and research assistant Michael McEvoy, both of the University of Colorado Boulder.

The "robotic materials" being developed by Correll Lab and others are often inspired by nature, ...

Biologists at the University of California, San Diego have developed a new method for generating mutations in both copies of a gene in a single generation that could rapidly accelerate genetic research on diverse species and provide scientists with a powerful new tool to control insect borne diseases such as malaria as well as animal and plant pests.

Their achievement was published today in an advance online paper in the journal Science. It was accomplished by two biologists at UC San Diego working on the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster who employed a new genomic technology ...

Berkeley -- Scientists at the University of California, Berkeley, have identified a new molecular pathway critical to aging, and confirmed that the process can be manipulated to help make old blood like new again.

The researchers found that blood stem cells' ability to repair damage caused by inappropriate protein folding in the mitochondria, a cell's energy station, is critical to their survival and regenerative capacity.

The discovery, to be published in the March 20 issue of the journal Science, has implications for research on reversing the signs of aging, a process ...

Without better local management, the world's most iconic ecosystems are at risk of collapse under climate change, say researchers in a study published in the journal Science.

The international team of researchers say protecting places of global environmental importance such as the Great Barrier Reef and the Amazon rainforest from climate change requires reducing the other pressures they face, for example overfishing, fertilizer pollution or land clearing.

The researchers warn that localised issues, such as declining water quality from nutrient pollution or deforestation, ...

The 2014 chemistry Nobel Prize recognized important microscopy research that enabled greatly improved spatial resolution. This innovation, resulting in nanometer resolution, was made possible by making the source (the emitter) of the illumination quite small and by moving it quite close to the object being imaged. One problem with this approach is that in such proximity, the emitter and object can interact with each other, blurring the resulting image. Now, a new JQI study has shown how to sharpen nanoscale microscopy (nanoscopy) even more by better locating the exact ...

Sifting through the center of the Milky Way galaxy, astronomers have made the first direct observations - using an infrared telescope aboard a modified Boeing 747 - of cosmic building-block dust resulting from an ancient supernova.

"Dust itself is very important because it's the stuff that forms stars and planets, like the sun and Earth, respectively, so to know where it comes from is an important question," said lead author Ryan Lau, Cornell postdoctoral associate for astronomy, in research published March 19 in Science Express. "Our work strongly reinforces the theory ...

Researchers from Banner Alzheimer's Institute (BAI) have developed a new brain image analysis method to better track the progression of beta-amyloid plaque deposition, a characteristic brain abnormality in Alzheimer's disease, according to a study published in the March issue of the Journal of Nuclear Medicine. Investigators also believe this new approach may make it easier to evaluate investigational anti-amyloid treatments in clinical trials.

During the last decade, researchers have been using positron emission topography (PET) to assess amyloid plaque deposition in ...

A psychology study from The University of Texas at Austin sheds new light on today's standards of beauty, attributing modern men's preferences for women with a curvy backside to prehistoric influences.

The study, published online in Evolution and Human Behavior, investigated men's mate preference for women with a "theoretically optimal angle of lumbar curvature," a 45.5 degree curve from back to buttocks allowing ancestral women to better support, provide for, and carry out multiple pregnancies.

"What's fascinating about this research is that it is yet another scientific ...

WASHINGTON, March 19, 2015 -- It's a simple claim made on thousands of personal care products for adults and kids: hypoallergenic. But what does that actually mean? Turns out, it can mean whatever manufacturers want it to mean, and that can leave you feeling itchy. Speaking of Chemistry is back this week with Sophia Cai explaining why "hypoallergenic" isn't really a thing. Check it out here: http://youtu.be/lXh8bnqMOZs.

Speaking of Chemistry is a production of Chemical & Engineering News, a weekly magazine of the American Chemical Society. The program features fascinating, ...

The Canadian research community on high-temperature superconductivity continues to lead this exciting scientific field with groundbreaking results coming hot on the heels of big theoretical questions.

The latest breakthrough, which will be published March 20 in Science, answers a key question on the microscopic electronic structure of cuprate superconductors, the most celebrated material family in our quest for true room-temperature superconductivity.

This result is the product of a longstanding close collaboration between the University of British Columbia Quantum ...