(Press-News.org) Australian scientists have discovered a new population of 'memory' immune cells, throwing light on what the body does when it sees a microbe for the second time. This insight, and others like it, will enable the development of more targeted and effective vaccines.

Two of the key players in our immune systems are white blood cells known as 'T cells' and 'B cells'. B cells make antibodies, and T cells either help B cells make antibodies, or else kill invading microbes. B cells and killer T cells are known to leave behind 'memory' cells to patrol the body, after they have subdued an infection.

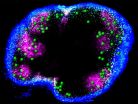

The newly identified 'Follicular Memory T cells' are related to the T helper cells but unlike circulating memory B and T cells, they position themselves near the entrance of lymph nodes, particularly those that are potential sites of microbe re-entry.

Humans have evolved an astonishing way of dealing with infection. When a microbe containing 'antigens' (parts of the microbe that trigger immune responses) penetrates the skin, it quickly gets transferred to our lymph nodes, which are interspersed throughout our bodies.

Lymph nodes are purpose-built structures for trapping microbes and manufacturing the antibodies needed to neutralise them. They contain clearly demarcated zones, populated by different kinds of immune cells, carrying out specialised tasks.

When a microbe arrives at the lymph node, it is trapped by sentinel immune cells, called subcapsular sinus macrophages, which have evolved to act as 'the flypaper of the lymph node'. This sets off a chain reaction that results in the formation of a 'germinal centre', from which antibody-producing cells are made.

Before this can happen, B cells have to be able to perceive the microbe and then pass a number of quality control filters to ensure only those cells best able to make neutralising antibodies are selected.

A subset of T helper cells, known as Follicular T helper (Tfh) cells, are critical for the antibody response because they help B cells navigate through these quality control filters. This process, from the arrival of a microbe to the creation of potent antibodies, is known as the 'primary antibody response' and is already well studied and described.

The new study examines the 'secondary antibody response', when the body next encounters the same invader. The findings are published in the prestigious journal Immunity, now online.

Dr Tri Phan, Dr Tatyana Chtanova, Dr Dan Suan, Dr Akira Nguyen and Imogen Moran, from Sydney's Garvan Institute of Medical Research, demonstrated that Tfh cells behave very differently during the primary and secondary responses.

During the primary response, they are confined within the germinal centre; during the secondary response they are free to leave the germinal centre and "surf the lymph system" in search of memory B cells to activate.

The researchers tracked the primary and secondary immune responses in mice, by using a laser to tag the cells deep inside the lymph node and then follow them with a special microscope that can be used in living animals.

"What we saw in the secondary response really surprised us," said Dr Tri Phan. "The memory cells weren't coming from the blood, as expected. They were already in the lymph node, and only in the lymph node closest to the original site of infection.

"This is important because, until now, people have thought that memory is provided by circulating cells.

"In addition to the memory cells that are on patrol in the circulation, we show that the immune system also leaves behind a garrison of memory cells - follicular memory T cells - strategically positioned at the entrance of the lymph node to screen for return of their particular microbe of interest.

"We could see the follicular memory T cells talking to subcapsular sinus macrophages - the highly specialised flypaper cells that trap antigen - checking their catch to see if it was of interest.

"When the memory cell sees its target on the macrophage, it becomes activated and the cell divides to start making a new army of Tfh cells. This second generation of Tfh cells is then sent out via the lymphatic system to other parts of the body to fight the infection.

"We think that the subcapsular sinus macrophages are incredibly important to the process. Understanding how to target antigen to them, and in turn to the memory cells, will help make better, more effective vaccines.

"The more insight we have into these complex processes from a whole body perspective, the better. Our laboratory is fortunate to have the technology that allows us to view cellular interactions as they play out in real-time on such a large scale."

INFORMATION:

At some point, probably 50,000 to 100,000 years ago, humans began talking to one another in a uniquely complex form. It is easy to imagine this epochal change as cavemen grunting, or hunter-gatherers mumbling and pointing. But in a new paper, an MIT linguist contends that human language likely developed quite rapidly into a sophisticated system: Instead of mumbles and grunts, people deployed syntax and structures resembling the ones we use today.

"The hierarchical complexity found in present-day language is likely to have been present in human language since its emergence," ...

Alcoholism takes a toll on every aspect of a person's life, including skin problems. Now, a new research report appearing in the April 2015 issue of the Journal of Leukocyte Biology, helps explain why this happens and what might be done to address it. In the report, researchers used mice show how chronic alcohol intake compromises the skin's protective immune response. They also were able to show how certain interventions may improve the skin's immune response. Ultimately, the hope is that this research could aid in the development of immune-based therapies to combat skin ...

GAINESVILLE, Fla. -- Increasing state alcohol taxes could prevent thousands of deaths a year from car crashes, say University of Florida Health researchers, who found alcohol-related motor vehicle crashes decreased after taxes on beer, wine and spirits went up in Illinois.

A team of UF Health researchers discovered that fatal alcohol-related car crashes in Illinois declined 26 percent after a 2009 increase in alcohol tax. The decrease was even more marked for young people, at 37 percent.

The reduction was similar for crashes involving alcohol-impaired drivers and extremely ...

A history of depression may put women at risk for developing diabetes during pregnancy, according to research published in the latest issue of the Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing by researchers from Loyola University Chicago Marcella Niehoff School of Nursing (MNSON). This study also pointed to how common depression is during pregnancy and the need for screening and education.

"Women with a history of depression should be aware of their risk for gestational diabetes during pregnancy and raise the issue with their doctor," said Mary Byrn, PhD, RN, ...

WASHINGTON, DC, March 31, 2015 -- People whose sexual identities changed toward same-sex attraction in early adulthood reported more symptoms of depression in a nationwide survey than those whose sexual orientations did not change or changed in the opposite direction, according to a new study by a University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) sociologist.

The study, "Sexual Orientation Identity Change and Depressive Symptoms: A Longitudinal Analysis," which appears in the current issue of the Journal of Health and Social Behavior, found that gay, lesbian, and bisexual people ...

This news release is available in French. Domestic violence takes many forms. The control of a woman's reproductive choices by her partner is one of them. A major study published in PLOS One, led by McGill PhD student Lauren Maxwell, showed that women who are abused by their partner or ex-partner are much less likely to use contraception; this exposes them to sexually transmitted diseases and leads to more frequent unintended pregnancies and abortions. These findings could influence how physicians provide contraceptive counselling.

Negotiating for contraception

A ...

The latest challenges of early breast cancer research include refining classification and predicting treatment responses, according to a report on the 14th St Gallen International Breast Cancer Consensus Conference, published in ecancermedicalscience.

The 2015 conference assembled nearly 3200 participants from 134 countries worldwide in Vienna, Austria to decide the consensus of breast cancer care and treatment.

Led by Dr Angela Esposito of the European Institute of Oncology, Milan, Italy, the report highlights some of the controversial areas discussed in this important ...

Children who received training grasped concept of Brace principle

Analogical comparison is a natural and engaging process for

children

Findings reveal ways to support children's learning in and out of

school

EVANSTON, Ill. --- Children love to build things. Often half the fun for them is building something and then knocking it down. But in a study carried out in the Chicago Children's Museum, children had just as much fun learning how to keep their masterpieces upright -- they learned a key elementary engineering principle.

"The use of a diagonal ...

More midriff, cleavage and muscle is seen in MTV's popular television docusoaps such as The Real World, Jersey Shore or Laguna Beach than in the average American household. Semi-naked brawny Adonises and even more scantily clad thin women strut around on screen simply to grab the audience's attention. In the process, they present a warped view to young viewers about how they should look. Such docusoaps are definitely more ideal than real, say Mark Flynn of the Coastal Carolina University and Sung-Yeon Park of Bowling Green State University in the US. The findings, which ...

During prenatal development, the brains of most animals, including humans, develop specifically male or female characteristics. In most species, some portions of male and female brains are a different size, and may have a different number of neurons and synapses. However, scientists have known little about the details of how this differentiation occurs. Now, a new study by researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UM SOM) has illuminated details about this process.

Margaret McCarthy, PhD, professor and chairman of the Department of Pharmacology, studied ...