Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, the University of California, Santa Barbara, and Johns Hopkins University have taken a network science approach to this question. In a new study, they measured the connections between different brain regions as participants learned to play a simple game. The differences in neural activity between the quickest and slowest learners provide new insight into what is happening in the brain during the learning process and the role that interactions between different regions play.

Their findings suggest that recruiting unnecessary parts of the brain for a given task, akin to over-thinking the problem, plays a critical role in this difference.

The study was conducted by Danielle Bassett, the Skirkanich Assistant Professor of Innovation in Penn's School of Engineering and Applied Science's departments of Bioengineering and of Electrical and Systems Engineering; Muzhi Yang, a graduate student in Penn Arts & Science's Applied Mathematics and Computational Science program; Nicholas Wymbs of the Human Brain Physiology and Stimulation Laboratory at Johns Hopkins; and Scott Grafton of the UCSB Brain Imaging Center.

It was published in Nature Neuroscience.

Wymbs and Grafton tasked study participants at UCSB to play a simple game while their brains were scanned with fMRI. The technique measures neural activity by tracking the flow of blood in the brain, highlighting how regions are involved in a given task.

The game was to respond to a sequence of color-coded notes by pressing the corresponding button on a hand-held controller. There were six pre-determined sequences of 10 notes each, shown multiple times during the scanning sessions.

The researchers instructed participants to play the sequences as quickly and as accurately as possible, responding to the cues they saw on a screen.

Participants were also required to practice the sequences at home; the researchers remotely monitored these sessions. The participants returned to the scanner two, four and six weeks later, to see how well their home practice sessions had helped them to master the skill.

All the participants' completion times dropped during the course of the study but did so at different rates. Some picked up the sequences immediately, while others gradually improved during the six-week period.

Bassett, an expert in network science, developed novel analysis methods to determine what was happening in the participants' brains that correlated with these differences. But rather than trying to find a single spot in the brain that was more or less active, the researchers investigated the learning process as the product of a complex, dynamic network.

"We weren't using the traditional fMRI approach," Bassett said, "where you pick a region of interest and see if it lights up. We looked at the whole brain at once and saw which parts were communicating with each other the most."

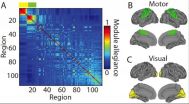

They compared the activation patterns of 112 anatomical regions of the brain, measuring the degree to which they mirrored one another. The more two regions' patterns matched, the more they were considered to be in communication. By graphing those connections, hot spots of highly interconnected regions emerged.

"When a network scientist looks at these graphs, they see what is known as community structure," Bassett said. "There are sets of nodes in a network that are really densely interconnected to each other. Everything else is either independent or very loosely connected with only a few lines."

Bassett and her colleagues used a technique known as dynamic community detection, which employs algorithms to determine which nodes are incorporated into these clusters and how their interactions change over time. This allowed the researchers to measure how common it was for any two nodes to remain in the same cluster while subjects practiced the same sequence about 10 times.

Through these comparisons, the researchers found overarching trends about how regions responsible for different functions worked together.

"If we look just at the visual and the motor blocks," Bassett said, "they have a lot of connectivity between them during the first few trials, but, as the experiment progresses, they become essentially autonomous. The part of the brain that controls the movement of your fingers and the part of your brain that processes the visual stimulus don't really interact at all by the end."

In some ways, this trend was unsurprising. The researchers were essentially seeing the learning process on the neurological level, with the participants' brains reorganizing the flow of activity as they picked up this new skill.

"What we think is happening," Bassett said, " is that they see the first few elements of a sequence and realize which one it is. Then they can play it from motor memory. There no longer needs to be constant communication between the visual stream and their motor control."

With the neurological correlates of the learning process coming into focus, the researchers could delve into the differences between participants, which might explain why some learned the sequences faster than others.

Counterintuitively, the participants who showed decreased neural activity learned the fastest. The critical distinction was in areas that were not directly related to seeing the cues or playing the notes: the frontal cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex.

"The reason this is interesting is that those two areas are hubs of the cognitive control network," Bassett said. "It's the people who can turn off the communication to these parts of their brain the quickest who have the steepest drop-off in their completion times."

These cognitive control centers are thought to be most responsible for what is known as "executive function." This neurological trait is associated with making and following through with plans, spotting and avoiding errors and other higher-order types of thinking. Good executive function is necessary for complex tasks but might actually be a hindrance to mastering simple ones.

"It seems like those other parts are getting in the way for the slower learners. It's almost like they're trying too hard and overthinking it," Bassett said.

The frontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex are some of the last regions of the brain to fully develop in humans, so this dynamic may also help explain how children are able to acquire new skills so quickly as compared to adults.

Further research will delve into why some people are better than others at shutting down the connections in these parts of the brains.

INFORMATION:

The research was supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, Army Research Laboratory, Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics, National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health and U.S. Army Research Office.