(Press-News.org) The secret communication of gibbons has been interpreted for the first time in a study published in the open access journal BMC Evolutionary Biology. The research reveals the likely meaning of a number of distinct gibbon whispers, or 'hoo' calls, responding to particular events and types of predator, and could provide clues on the evolution of human speech.

While lar gibbons (Hylobates lar) are mainly known for their loud and conspicuous songs, they can also produce a number of soft call types known as 'hoo's. These subtle calls have been alluded to in studies dating back to 1940, but due to their volume, they are virtually indistinguishable to the human ear and have been difficult to record and analyse.

Researchers using modern recording technology and computer analysis have revealed that distinct hoo calls are made in response to specific events, such as foraging and encountering neighbours, and that subtle differences even distinguish between different predators when used as a warning.

Lead author Esther Clarke said: "These animals are extraordinarily vocal creatures and give us the rare opportunity to study the evolution of complex vocal communication in a non-human primate. In the future, gibbon vocalisations may reveal much about the processes that shape vocal communication, and because they are an ape species, they may be one of our best hopes at tracing the evolution of human communication."

The researchers spent almost four months following lar gibbon groups around the forests of North-eastern Thailand. The gibbons were usually followed from the first encounter in the morning until they had located their evening sleeping tree, while researchers recorded their hoos and noted the event that elicited the response. From the recordings they extracted over 450 hoo sounds and used computer analysis to find links between audio patterns and the context in which they were recorded.

The gibbons reliably produced individual hoo calls for different contexts, including foraging, predator detection, encountering neighbours, and as part of duet songs by mated pairs. In addition to differences between contexts, the team also discovered subtle hoo variations within contexts, for example to distinguish between different types of predator.

The team investigated the responses to a range of predators including clouded leopards, tigers, pythons, and raptors including eagle owls and crested serpent eagles. In addition to real predator observations, they presented fake model predators in realistic poses for the rarer animals.

Raptor hoos were acoustically distinct - less intense, shorter and with a smaller frequency span than the other hoos, making them the least audible. Raptors hear best in the range of 1-4kHz, while gibbon hoos are consistently below the 1kHz threshold. The raptor hoos were the lowest frequency of all and could help gibbons avoid attracting the attention of the predator.

Tiger and leopard hoos were similar, suggesting that callers perceived these two predators as belonging to the same 'big cat' class.

While both gibbon sexes displayed similar hoo calls, female calls were lower in frequency than male ones. The researchers say this is surprising, as among mammals, males tend to have lower frequency voices than females.

Females also typically did not produce hoo vocalisations when encountering neighbours and often remained passive and removed, while males engaged and interacted with neighbouring individuals.

The researchers say the study is of direct relevance for the on-going debate about the evolution of human speech. The ability to produce calls that are context-specific is necessary for communication where an actor refers a recipient's attention to an external event.

This behaviour appears to be widespread and was likely present in the ancestor of modern primates and humans. The acoustic variation seen in gibbon hoos in particular may be similar to human speech, in which subtle acoustic parameters, like pitch, can be important carriers of meaning.

INFORMATION:

Media Contact

Shane Canning

Media Manager

BioMed Central

T: +44 (0)20 3192 2243

M: +44 (0)78 2598 4543

E: shane.canning@biomedcentral.com

Notes to editors:

1. Audio, photos and other multimedia are available, if you would like access to these please contact Shane Canning (shane.canning@biomedcentral.com)

All material should be credited to Esther Clarke.

2. Research article:

Esther Clarke, Ulrich H Reichard and Klaus Zuberbuhler

Context-specific close-range "hoo" calls in wild gibbons (Hylobates lar)

BMC Evolutionary Biology 2015

doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0332-2

For a copy of the article during the embargo period please contact Shane Canning (shane.canning@biomedcentral.com)

After embargo, article available at journal website here: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12862-015-0332-2

3. BMC Evolutionary Biology is an open access, peer-reviewed journal that considers articles on all aspects of molecular and non-molecular evolution of all organisms, as well as phylogenetics and palaeontology.

BMC Evolutionary Biology is part of the BMC series which publishes subject-specific journals focused on the needs of individual research communities across all areas of biology and medicine. We offer an efficient, fair and friendly peer review service, and are committed to publishing all sound science, provided that there is some advance in knowledge presented by the work.

4. BioMed Central is an STM (Science, Technology and Medicine) publisher which has pioneered the open access publishing model. All peer-reviewed research articles published by BioMed Central are made immediately and freely accessible online, and are licensed to allow redistribution and reuse. BioMed Central is part of Springer Science+Business Media, a leading global publisher in the STM sector. http://www.biomedcentral.com

Life has adapted to all sorts of extreme environments on Earth, among them, animals like the deer mouse, shimmying and shivering about, and having to squeeze enough energy from the cold, thin air to fuel their bodies and survive.

Now, in a new publication in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution, Scott, Cheviron et al., have examined the underlying muscle physiology from a group of highland and lowland deer mice. Deer mice were chosen because they exhibit the most extreme altitude range of any North American mammal, occurring below sea levels in Death Valley to ...

Cold Spring Harbor, NY - The prefrontal cortex (PFC) plays an important role in cognitive functions such as attention, memory and decision-making. Faulty wiring between PFC and other brain areas is thought to give rise to a variety of cognitive disorders. Disruptions to one particular brain circuit--between the PFC and another part of the brain called the thalamus--have been associated with schizophrenia, but the mechanistic details are unknown. Now, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory scientists have discovered an inhibitory connection between these brain areas in mice that ...

The Burgess Shale Formation, in the Canadian Rockies of British Columbia, is one of the most famous fossil locations in the world. A recent Palaeontology study introduces a 508 million year old (middle Cambrian) arthropod--called Yawunik kootenayi--from exceptionally preserved specimens of the new Marble Canyon locality within the Burgess Shale Formation.

Its frontal appendage--the "megacheiran great appendage"--is remarkably adorned with teeth, emphasizing an advanced predatory function. The appendage also had long hair-like flagella at the end that likely served a sensory ...

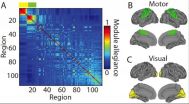

Why do some people learn a new skill right away, while others only gradually improve? Whatever else may be different about their lives, something must be happening in their brains that captures this variation.

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, the University of California, Santa Barbara, and Johns Hopkins University have taken a network science approach to this question. In a new study, they measured the connections between different brain regions as participants learned to play a simple game. The differences in neural activity between the quickest and slowest ...

The results appear in the 2015 2nd issue of the journal of Human Genome Variation. To see a video about the partnership between Champions and Insilico, visit: http://tinyurl.com/InsilicoChampions .

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States. More than 50,000 people die of CRC each year due to tumor spreading to other organs and almost half of all newly diagnosed patients are in an advanced stage of cancer (metastatic CRC or mCRC) when they are first diagnosed.

With the development ...

A Northwestern University research team potentially has found a safer way to keep blood vessels healthy during and after surgery.

During open-heart procedures, physicians administer large doses of a blood-thinning drug called heparin to prevent clot formation. When given too much heparin, patients can develop complications from excessive bleeding. A common antidote is the compound protamine sulfate, which binds to heparin to reverse its effects.

"Protamine is a natural compound that has been used in surgeries for many decades," said Guillermo Ameer, professor of biomedical ...

The combination of two well-known drugs will have unprecedented effects on pain management, says new research from Queen's.

Combining morphine, a narcotic pain reliever, and nortriptyline, an antidepressant, has been found to successfully relieve chronic neuropathic pain - or a localized sensation of pain due to abnormal function of the nervous system - in 87 per cent of patients, and significantly better than with either drug alone.

"Chronic pain is an increasingly common problem and can exert disastrous personal, societal, and socio-economic impacts on patients, their ...

In the largest study of its kind to date, researchers at Stanford University School of Medicine and their colleagues have found that worldwide only a limited number of mutations are responsible for most cases of transmission of drug-resistant HIV.

HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, can mutate in the presence of antiviral drugs, and these mutations can be transmitted from one person to the next.

In the new study of more than 50,000 patients in 111 countries, the researchers found a small group of mutations accounted for a majority of the cases of transmission-related resistance ...

Washington, DC (April 7, 2015) - Greater availability of percutaneous mechanical circulatory support (MCS) devices for treatment of heart failure is helping expand treatment options for a rapidly growing number of acutely and chronically ill cardiac patients who could benefit from the devices. An expert consensus statement released today by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI), American College of Cardiology (ACC), Heart Failure Society of America (HFSA) and The Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) provides new guidance to help physicians match ...

Only a limited number of surveillance drug-resistance mutations (SDRMs) are responsible for most instances of non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI)- and nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI)-associated resistance, and most strains of HIV-1 transmitted drug resistance (TDR) in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and south/southeast Asia (SSEA) arose independently, according to a study published this week in PLOS Medicine. The study, led by Soo-Yon Rhee of Stanford University, and colleagues, came to these conclusions after analyzing individual virus sequences ...