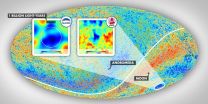

(Press-News.org) In 2004, astronomers examining a map of the radiation leftover from the Big Bang (the cosmic microwave background, or CMB) discovered the Cold Spot, a larger-than-expected unusually cold area of the sky. The physics surrounding the Big Bang theory predicts warmer and cooler spots of various sizes in the infant universe, but a spot this large and this cold was unexpected.

Now, a team of astronomers led by Dr. Istvan Szapudi of the Institute for Astronomy at the University of Hawaii at Manoa may have found an explanation for the existence of the Cold Spot, which Szapudi says may be "the largest individual structure ever identified by humanity."

If the Cold Spot originated from the Big Bang itself, it could be a rare sign of exotic physics that the standard cosmology (basically, the Big Bang theory and related physics) does not explain. If, however, it is caused by a foreground structure between us and the CMB, it would be a sign that there is an extremely rare large-scale structure in the mass distribution of the universe.

Using data from Hawaii's Pan-STARRS1 (PS1) telescope located on Haleakala, Maui, and NASA's Wide Field Survey Explorer (WISE) satellite, Szapudi's team discovered a large supervoid, a vast region 1.8 billion light-years across, in which the density of galaxies is much lower than usual in the known universe. This void was found by combining observations taken by PS1 at optical wavelengths with observations taken by WISE at infrared wavelengths to estimate the distance to and position of each galaxy in that part of the sky.

Earlier studies, also done in Hawaii, observed a much smaller area in the direction of the Cold Spot, but they could establish only that no very distant structure is in that part of the sky. Paradoxically, identifying nearby large structures is harder than finding distant ones, since we must map larger portions of the sky to see the closer structures. The large three-dimensional sky maps created from PS1 and WISE by Dr. András Kovács (Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary) were thus essential for this study. The supervoid is only about 3 billion light-years away from us, a relatively short distance in the cosmic scheme of things.

Imagine there is a huge void with very little matter between you (the observer) and the CMB. Now think of the void as a hill. As the light enters the void, it must climb this hill. If the universe were not undergoing accelerating expansion, then the void would not evolve significantly, and light would descend the hill and regain the energy it lost as it exits the void. But with the accelerating expansion, the hill is measurably stretched as the light is traveling over it. By the time the light descends the hill, the hill has gotten flatter than when the light entered, so the light cannot pick up all the energy it lost upon entering the void. The light exits the void with less energy, and therefore at a longer wavelength, which corresponds to a colder temperature.

Getting through a supervoid can take millions of years, even at the speed of light, so this measurable effect, known as the Integrated Sachs-Wolfe (ISW) effect, might provide the first explanation one of the most significant anomalies found to date in the CMB, first by a NASA satellite called the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP), and more recently, by Planck, a satellite launched by the European Space Agency.

While the existence of the supervoid and its expected effect on the CMB do not fully explain the Cold Spot, it is very unlikely that the supervoid and the Cold Spot at the same location are a coincidence. The team will continue its work using improved data from PS1 and from the Dark Energy Survey being conducted with a telescope in Chile to study the Cold Spot and supervoid, as well as another large void located near the constellation Draco.

The study is being published online on April 20 in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society by the Oxford University Press. In addition to Szapudi and Kovács, researchers who contributed to this study include UH Manoa alumnus Benjamin Granett (now at the National Institute for Astrophysics, Italy), Zsolt Frei (Eötvös Loránd), and Joseph Silk (Johns Hopkins).

INFORMATION:

Founded in 1967, the Institute for Astronomy at the University of Hawaii at Manoa conducts research into galaxies, cosmology, stars, planets, and the sun. Its faculty and staff are also involved in astronomy education, deep space missions, and in the development and management of the observatories on Haleakala and Maunakea. The Institute operates facilities on the islands of Oahu, Maui, and Hawaii.

The Pan-STARRS1 Surveys (PS1) have been made possible through contributions by the Institute for Astronomy, the University of Hawaii, the Pan-STARRS Project Office, the Max-Planck Society and its participating institutes, the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Heidelberg and the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, Garching, The Johns Hopkins University, Durham University, the University of Edinburgh, the Queen's University Belfast, the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, the Las Cumbres Observatory Global Telescope Network Incorporated, the National Central University of Taiwan, the Space Telescope Science Institute, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration under Grant No. NNX08AR22G issued through the Planetary Science Division of the NASA Science Mission Directorate, the National Science Foundation Grant No. AST-1238877, the University of Maryland, Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE), and the Los Alamos National Laboratory.

Researcher contacts:

Dr. István Szapudi,

+1 808 956-6196,

szapudi@ifa.hawaii.edu

Dr. András Kovács,

+34 93 176 3966,

akovacs@ifae.es

A badly dubbed foreign film makes a viewer yearn for subtitles; even subtle discrepancies between words spoken and facial motion are easy to detect. That's less likely with a method developed by Disney Research that analyzes an actor's speech motions to literally put new words in his mouth.

The researchers found that the facial movements an actor makes when saying "clean swatches," for instance, are the same as those for such phrases as "likes swats," "then swine," or "need no pots."

Sarah Taylor and her colleagues at Disney Research Pittsburgh and the University of ...

Leading doctors today [Monday 20 April, 2015] warn that medical and public recognition of sepsis--thought to contribute to between a third and a half of all hospital deaths--must improve if the number of deaths from this common and potentially life-threatening condition are to fall.

In a new Commission, published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases, Professor Jonathan Cohen and colleagues outline the current state of research into this little-understood condition, and highlight priority areas for future investigation.

Sepsis--sometimes misleadingly called "blood poisoning"--is ...

The college graduation rate for students who have lived in foster care is 3 percent, among the lowest of any demographic group in the country. And this rate is unlikely to improve unless community colleges institute formal programs to assist foster youth both financially and academically, concludes a new study by researchers at University of the Pacific.

The findings will be presented during the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association in Chicago on Sunday, April 19.

"Informal programs are less likely to work since foster youth lack guidance ...

PHILADELPHIA-- Once again, researchers at Penn's Abramson Cancer Center have extended the reach of the immune system in the fight against metastatic melanoma, this time by combining the checkpoint inhibitor tremelimumab with an anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody drug. The first-of-its-kind study found the dual treatments to be safe and elicit a clinical response in patients, according to new results from a phase I trial to be presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2015 on Sunday, April 19.

Researchers include first author David L. Bajor, MD, instructor of Medicine in the division ...

PHILADELPHIA -- Women diagnosed with breast cancer are often told not to eat soyfoods or soy-based supplements because they can interfere with anti-estrogen treatment. But new research being presented at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting 2015 could eventually impact that advice, because in animals, a long history of eating soyfoods boosts the immune response against breast tumors, reducing cancer recurrence.

The study, conducted at Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, could offer good news to some women whose diet has long ...

PHILADELPHIA, April 19, 2015 - Broccoli sprout extract protects against oral cancer in mice and proved tolerable in a small group of healthy human volunteers, the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (UPCI), partner with UPMC CancerCenter, announced today at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting in Philadelphia.

The promising results will be further explored in a human clinical trial, which will recruit participants at high risk for head and neck cancer recurrence later this year. This research is funded through Pitt's Specialized Program ...

PHILADEPHIA, April 19, 2015 - Identifying molecular changes that occur in tissue after chemotherapy could be crucial in advancing treatments for ovarian cancer, according to research from Magee-Womens Research Institute and Foundation (MWRIF) and the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (UPCI), partner with UPMC CancerCenter, presented today at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting 2015.

For years now, intraperitoneal chemotherapy, a treatment which involves filling the abdominal cavity with chemotherapy drugs after surgery, has been ...

PHILADELPHIA -Genetically modified versions of patients' own immune cells successfully traveled to tumors they were designed to attack in an early-stage trial for mesothelioma and pancreatic and ovarian cancers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. The data adds to a growing body of research showing the promise of CAR T cell technology. The interim results will be presented at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting 2015, April 18-22.

"The goal of this phase I trial was to study the safety and feasibility of ...

Using mobile apps in preschool classrooms may help improve early literacy skills and boost school readiness for low-income children, according to research by NYU's Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development.

"Guided use of an educational app may be a source of motivation and engagement for children in their early years," said Susan B. Neuman, professor of childhood and literacy education at NYU Steinhardt and the study's author. "The purpose of our study was to examine if a motivating app could accelerate children's learning, which it did."

Neuman ...

Schools must track the academic progress of homeless students with as much care as they track special education, Title I and English language learner students, according to researchers at University of the Pacific.

"In an age of accountability, schools focus their efforts and attention on the students they are mandated to report on," said Ronald Hallett, associate professor of education and lead author of the study. "We need to realign our policies and procedures if we are going to improve academic outcomes for homeless and highly mobile students."

Hallett and his colleagues ...