(Press-News.org) NEW YORK (April 20, 2015) -- Genomic studies have illuminated the ways in which malfunctioning genes can drive cancer growth while stunting the therapeutic effects of chemotherapy and other treatments. But new findings from Weill Cornell Medical College investigators indicate that these genes are only partly to blame for why treatment that was at one point effective ultimately fails for about 40 percent of patients diagnosed with the most common form of non-Hodgkin Lymphoma.

The study, published April 20 in Nature Communications, suggests that global changes in cancer cells' epigenome that turn normal genes on when they should be off, and vice versa, may be a powerful force in determining disease progression. The investigators made this discovery by reviewing biopsies taken from patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) before treatment and again after the treatment failed and cancer resurged. They compared the two samples and found that the epigenome in these patients' cancer cells had substantially changed after treatment.

They also found that the global epigenome of pre-treatment biopsies was substantially different in patients whose disease did not recur compared to patients whose disease came back. The researchers found more cell-to-cell heterogeneity, that is, a greater variety of epigenetic patterns in patients who relapsed.

The epigenome, which surrounds genetic DNA like a bubble, is powerful; it can determine which genes are turned on or off, influencing the production of proteins -- the workhorses of human biology. The epigenome can modify gene expression by adding or removing a chemical compound, known as a methyl group, to a specific place in a gene's DNA. Adding a methyl group to a gene turns the gene off, and removing a methyl group allows a gene to turn on when it shouldn't.

This explains why the findings are so significant, investigators say, because drugs that disrupt the epigenetic machinery in cancer cells might reverse treatment resistance and help chemotherapy and other drugs to do their jobs.

"This is the first study I know of in cancer that looks at changes in the epigenome before and after treatment, and what we found could ultimately make traditional treatments much more effective," said senior author Dr. Olivier Elemento, an associate professor of physiology and biophysics and head of the Laboratory of Cancer Systems Biology in the HRH Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Bin Abdulaziz Al-Saud Institute for Computational Biomedicine at Weill Cornell.

"The epigenome is flexible and can change faster than the genome can, but changes in the epigenome are lasting -- they are maintained from one cell division to the next," Dr. Elemento said.

Epigenetic modifications can therefore be inherited, or can be influenced by a person's environment, such as diet and pollutants. Yet the cause of global epigenetic changes in cancer, including DLBCL, Dr. Elemento added, is unknown.

To help uncover the role of epigenetic involvement, Dr. Elemento utilized biopsies banked by collaborators Dr. Giorgio Inghirami and Dr. Wayne Tam, who are blood cancer pathology specialists and lymphoma researchers at Weill Cornell.

In each sample set, investigators looked at sites in the epigenome where a methyl group was added or removed after cancer recurred. They found a change in methylation that occurred between 39,808 and 1,035,960 specific methylation sites, depending on the cancer sample. In addition, they identified between 78 and 13,162 differently methylated regions in the epigenome in relapsed cancer.

"These are massive changes -- given that the epigenome has 20 million methylation sites, our study shows that in some cases, up to one-twentieth of the entire epigenome is changed after treatment," Dr. Elemento said. "There are many more epigenetic changes than there are altered genes in DLBCL."

"Once you have changes in methylation, the end result is an imbalanced expression of proteins," added Dr. Inghirami, a professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at Weill Cornell. "The tumor after chemotherapy is not the same as the tumor before treatment. This why it is so critical to have biopsies before any treatment of either primary as well as of relapsed lesions."

Given how important the epigenome seems to be in cancer, the investigators say future success in this new avenue of research and treatment depends on collecting cancer biopsies from patients before and after treatment. They hope that this work will ultimately allow clinicians and researchers to predict treatment resistance in individual patients.

"By studying more samples, it may ultimately be possible to scan the most informative regions of the epigenome of a patient's lymphoma at diagnosis to predict whether treatment will be successful and whether the cancer may recur," said Dr. Tam, an associate professor of clinical pathology and laboratory medicine at Weill Cornell.

INFORMATION:

Weill Cornell Medical College

Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University's medical school located in New York City, is committed to excellence in research, teaching, patient care and the advancement of the art and science of medicine, locally, nationally and globally. Physicians and scientists of Weill Cornell Medical College are engaged in cutting-edge research from bench to bedside aimed at unlocking mysteries of the human body in health and sickness and toward developing new treatments and prevention strategies. In its commitment to global health and education, Weill Cornell has a strong presence in places such as Qatar, Tanzania, Haiti, Brazil, Austria and Turkey. Through the historic Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar, the Medical College is the first in the U.S. to offer its M.D. degree overseas. Weill Cornell is the birthplace of many medical advances -- including the development of the Pap test for cervical cancer, the synthesis of penicillin, the first successful embryo-biopsy pregnancy and birth in the U.S., the first clinical trial of gene therapy for Parkinson's disease, and most recently, the world's first successful use of deep brain stimulation to treat a minimally conscious brain-injured patient. Weill Cornell Medical College is affiliated with NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, where its faculty provides comprehensive patient care at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. The Medical College is also affiliated with Houston Methodist. For more information, visit weill.cornell.edu.

Office of External Affairs

Weill Cornell Medical College

tel: 646.317.7401

email: pr@med.cornell.edu

Follow WCMC on:

Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram

A rigorous analysis of antimalarial drug quality conducted in Cambodia and Tanzania found no evidence of fake medicines, according to new research published in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.

But researchers warn that routine surveillance is crucial as poor quality medicines exist, leaving malaria patients at risk of dying and increasing the risk of drug resistance.

Previous reports had suggested that up to one third of antimalarials could be fake. Researchers from the Artemisinin-based Combination Therapy (ACT) Consortium at the London School ...

Dispensing of prescription opioid pain relievers and prescription opioid overdoses both dropped substantially after abuse-deterrent extended-release oxycodone hydrochloride was introduced on the pharmaceutical market and the narcotic drug propoxyphene was withdrawn from the U.S. market in 2010, according to an article published online by JAMA Internal Medicine.

The abuse-deterrent OxyContin formulation is resistant to crushing and dissolving, actions that have been used to bypass the extended-release mechanism to get a quicker and more intense high. Propoxyphene (also ...

Children whose families and pediatricians were most faithful to an obesity intervention program that included computerized clinical decision support for physicians and health coaching for families experienced the greatest improvements in body mass index (BMI), according to an article published online by JAMA Pediatrics.

The prevalence of childhood obesity in the United States remains at historically high levels. Clinical approaches that are cost-effective and scalable for obesity reduction in children are a public health priority. However, interventions to improve BMI ...

(Boston) - Results of a new study led by Boston Medical Center (BMC) researchers, in collaboration with Harvard Medical School (HMS), indicate that the introduction of abuse-deterrent OxyContin, coupled with the removal of propoxyphene from the US prescription marketplace, may have played a role in decreasing opioid prescribing and overdoses. The findings, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, showed that these two changes led to a 19 percent drop in prescription opioid supply that was mirrored by a 20 percent drop in prescription opioid overdose between August 2010 and ...

Poor quality medicines are a real and urgent threat that could undermine decades of successful efforts to combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis, according to the editors of a collection of journal articles published today. Scientists report up to 41 percent of specimens failed to meet quality standards in global studies of about 17,000 drug samples. Among the collection is an article describing the discovery of falsified and substandard malaria drugs that caused an estimated 122,350 deaths in African children in 2013. Other studies identified poor quality antibiotics, ...

Researchers from the University of Birmingham have identified an important new way in which our immune systems are regulated, and hope that understanding it will help tackle the debilitating effects of type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis and other serious diseases.

The team discovered a novel pathway that regulates the movement of pathogenic immune cells from the blood into tissue during an inflammatory response.

A healthy, efficient immune system ordinarily works to damp down inflammation and carefully regulate the magnitude of the response to infection and disease. ...

A University of Texas at Austin scientist, working with an international research team, has developed the most precise sequence map yet of U.S. cotton and will soon create an even more detailed map for navigating the complex cotton genome. The finding may help lead to an inexpensive version of American cotton that rivals the quality of luxurious Egyptian cotton and helps develop crops that use less water and fewer pesticides for a cotton that is easier on the skin and easier on the land.

Z. Jeffrey Chen and his collaborators, Tianzhen Zhang and Wangzhen Guo at Nanjing ...

Using the latest genome sequencing techniques, a research team led by scientists from UC San Francisco (UCSF), Baylor College of Medicine, and Texas Children's Hospital has identified a new autoimmune syndrome characterized by a combination of severe lung disease and arthritis that currently has no therapy.

The hereditary disorder, which appears in early childhood, had never been diagnosed as a single syndrome. The new research revealed that it is caused by mutations in a single gene that disrupt how proteins are shuttled around within cells. Patients with the newly ...

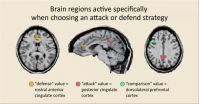

We often make quick strategic decisions to attack an opponent or defend our position, yet how we make them is not well understood. Now, researchers at the RIKEN Brain Science Institute in Japan have pinpointed specific brain regions related to this process by examining neural activity in people playing shogi, a Japanese form of chess. Published in Nature Neuroscience, the study shows that two different regions within the cingulate cortex--one toward the front of the brain and the other toward the back--separately encode the values of defensive and offensive strategies.

Like ...

Large amounts of methane - whether as free gas or as solid gas hydrates - can be found in the sea floor along the ocean shores. When the hydrates dissolve or when the gas finds pathways in the sea floor to ascend, the methane can be released into the water and rise to the surface. Once emitted into the atmosphere, it acts as a very potent greenhouse gas twenty times stronger than carbon dioxide. Fortunately, marine bacteria exist that consume part of the methane before it reaches the water surface. Geomicrobiologists and oceanographers from Switzerland, Germany, Great Britain ...