(Press-News.org) TORONTO, ON. (23 April, 2015) - A new study led by University of Toronto researcher Dr. David Lam has discovered the trigger behind the most severe forms of cancer pain. Released in top journal Pain this month, the study points to TMPRSS2 as the culprit: a gene that is also responsible for some of the most aggressive forms of androgen-fuelled cancers.

Head of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at the Faculty of Dentistry, Lam's research initially focused on cancers of the head and neck, which affect more than 550,000 people worldwide each year. Studies have shown that these types of cancers are the most painful, with sufferers experiencing pain that is immediate and localized, while pain treatment options are limited to opioid-family pharmaceuticals such as morphine.

It was while conducting clinical research at the University of California San Francisco, though, that Lam noticed something interesting. A majority of head and neck cancer patients are men - leading him to investigate a genetic marker with a known correlation to prostate cancer, TMPRSS2.

"Prostate cancer research already knows that if you have the TMPRSS2 gene marker, the prostate cancer is much more aggressive. They've also shown that this is androgen (male hormone) sensitive."

In his study, Lam, who is jointly appointed as a Consultant Surgeon at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre and a Clinician at the Mount Sinai Wasser Pain Management Centre, ascertained that TMPRSS2 was not only present in patients suffering from head and neck cancers - it was also prevalent in much greater quantities than in prostate cancer.

But was there a link to pain?

Visible on the surface of the cancer cells, TMPRSS2 comes into contact with the body's nerve pain receptors, which then triggers the pain. Lam was also able to determine a clear, correlative relationship between the two: the more TMPRSS2 that comes into contact with nerve pain receptors, the greater pain is provoked.

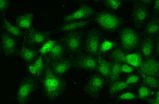

Lam and his fellow researchers followed up this observation by looking at different types of cancers with known pain associations - for instance, certain breast and melanoma cell lines. These cells were grown and labelled for the TMPRSS2 genetic marker.

According to clinical data, head and neck cancer is the most painful form of cancer, followed by prostate cancer, while melanoma, or skin cancer, sits at the bottom of the pain scale.

But what surprised the researchers was that the presence and amount of TMPRSS2 in these cancer cell cultures stood in exact correlation with the known level of pain each cancer causes.

"It was exactly what we know clinically about pain association," adds Lam.

A New Direction for Drug Research

The startling discovery of TMPRSS2's role in triggering cancer pain may lead to the creation of targeted cancer pain therapies that effectively shut down the expression of this gene or its ability to infiltrate pain receptors in the body.

Dr. Brian Schmidt, Professor at New York University College of Dentistry, Director of the Bluestone Center for Clinical Research and a co-author of the study states, "The discovery that TMPRSS2 drives cancer pain demonstrates another way that cancers lead to suffering. Inhibition of its activity in patients might provide a new form of treatment for cancer pain."

"Any cancer that is painful before initiating drug treatment - we can label the cancer cells for TMPRSS2 and look for this particular marker," explains Lam, who adds that the most effective approach to ending pain would be to target the production and expression of the pain gene.

But there may be other ramifications to the TMPRSS2 study: further research may yet uncover what role the increased expression of TMPRSS2 plays in the aggressiveness and morbidity rates associated with certain aggressive cancers - and whether or not shutting down the pain gene will have any other beneficial side effects than reducing discomfort.

The study also involved researchers from New York University and the Forsyth Institute (Cambridge).

INFORMATION:

ABOUT THE FACULTY OF DENTISTRY, UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO

Combining the rigours of biological and clinical research with a superior educational experience across a full range of undergraduate and graduate programs - with and without advanced specialty training - the Faculty of Dentistry at the University of Toronto has earned an international reputation as a premier dental research and training facility in Canada. From the cutting-edge science of biomaterials and microbiology, to next-generation nanoparticle and stem cell therapies, to ground-breaking population and access-to-care studies, the mission of the Faculty of Dentistry is to shape the future of dentistry and promote optimal health by striving for integrity and excellence in all aspects of research, education and clinical practice.

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- A 47-year-old African-American woman has heavy menstrual bleeding and iron-deficiency anemia. She reports the frequent need to urinate during the night and throughout the day. A colonoscopy is negative and an ultrasonography shows a modestly enlarged uterus with three uterine fibroids, noncancerous growths of the uterus. She is not planning to become pregnant. What are her options?

Elizabeth (Ebbie) Stewart, M.D., chair of Reproductive Endocrinology at Mayo Clinic, says the woman has several options, but determining her best option is guided by her ...

ANN ARBOR--Use of clean fuels and updated pollution control measures in the school buses 25 million children ride every day could result in 14 million fewer absences from school a year, based on a study by the University of Michigan and the University of Washington.

In research believed to be the first to measure the individual impact on children of the federal mandate to reduce diesel emissions, researchers found improved health and less absenteeism, especially among asthmatic children.

A change to ultra low sulfur diesel fuel reduced a marker for inflammation in ...

Boosting teenagers' ability to cope with online risks, rather than trying to stop them from using the Internet, may be a more practical and effective strategy for keeping them safe, according to a team of researchers.

In a study, more resilient teens were less likely to suffer negative effects even if they were frequently online, said Haiyan Jia, post-doctoral scholar in information sciences and technology.

"Internet exposure does not necessarily lead to negative effects, which means it's okay to go online, but the key seems to be learning how to cope with the stress ...

CAMBRIDGE, Mass--Drizzling honey on toast can produce mesmerizing, meandering patterns, as the syrupy fluid ripples and coils in a sticky, golden thread. Dribbling paint on canvas can produce similarly serpentine loops and waves.

The patterns created by such viscous fluids can be reproduced experimentally in a setup known as a "fluid mechanical sewing machine," in which an overhead nozzle deposits a thick fluid onto a moving conveyor belt. Researchers have carried out such experiments in an effort to identify the physical factors that influence the patterns that form. ...

April 23, 2015 - Interventional treatments--especially surgery--provide good functional outcomes and a high cure rate for patients with lower-grade arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) of the brain, reports the May issue of Neurosurgery, official journal of the Congress of Neurological Surgeons. The journal is published by Wolters Kluwer.

The findings contrast with a recent trial reporting better outcomes without surgery or other interventions for AVMs. "On the basis of these data, in appropriately selected patients, we recommend treatment for low-grade brain AVMs," concludes ...

A new study by the University of Chicago Booth School of Business Assistant Professor Amanda Sharkey and University of Utah Assistant Professor Patricia Bromley found that environmental ratings have spillover effects on other companies' behavior. Rated firms reduce their toxic emissions even more when their peers are also rated. In addition, rated peers can even motivate some unrated companies to reduce their emissions.

The research is unusual in that the role of peers in conditioning how firms respond to ratings systems has received little examination.

The study, "Can ...

SINCE its first use in the 1980s - a breakthrough dramatised in recent ITV series Code of a Killer - DNA profiling has been a vital tool for forensic investigators. Now researchers at the University of Huddersfield have solved one of its few limitations by successfully testing a technique for distinguishing between the DNA - or genetic fingerprint - of identical twins.

The probability of a DNA match between two unrelated individuals is about one in a billion. For two full siblings, the probability drops to one-in-10,000. But identical twins present exactly the same ...

This news release is available in German.

An individual's behaviour in risky situations is a distinct personality trait both in humans and animals that can have an immediate impact on longevity. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology in Seewiesen have now found differences in personality types for the first time in a population of free living field crickets. Risk-prone individuals showed a higher mortality as they stayed more often outside their burrow where they can be easily detected by predators, compared to risk averse individuals. Moreover, ...

Navigating through a cluttered environment at high speed is among the greatest challenges in biology - and it's one virtually all birds achieve with ease.

It's a feat David Williams hopes to understand.

A former post-doctoral fellow in the lab of Andrew Biewener, the Charles P. Lyman Professor of Biology, and a current post-doc at the University of Washington, Williams is the lead author of a study that shows birds use two highly stereotyped postures to avoid obstacles in flight. The study could open the door to new ways to program drones and other unmanned aerial ...

This news release is available in German.

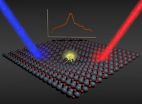

Researchers of Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) have unveiled an important step in the conversion of light into storable energy: Together with scientists of the Fritz Haber Institute in Berlin and the Aalto University in Helsinki/Finland, they studied the formation of so-called polarons in zinc oxide. The pseudoparticles travel through the photoactive material until they are converted into electrical or chemical energy at an interface. Their findings that are of relevance to photovoltaics among others are now published ...