(Press-News.org) CHICAGO --- Post-traumatic stress syndrome – when a severely stressful event triggers exaggerated and chronic fear – affects nearly 8 million people in the United States and is hard to treat. In a preclinical study, Northwestern Medicine scientists have for the first time identified the molecular cause of the debilitating condition and prevented it from occurring by injecting calming drugs into the brain within five hours of a traumatic event.

Northwestern researchers discovered the brain becomes overly stimulated after a traumatic event causes an ongoing, frenzied interaction between two brain proteins long after they should have disengaged.

"It's like they keep dancing even after the music stops," explained principal investigator Jelena Radulovic, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and Dunbar Scholar at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. When newly developed research drugs MPEP and MTEP were injected into the hippocampus, the calming drugs ended "the dance."

"We were able to stop the development of exaggerated fear with a simple, single drug treatment and found the window of time we have to intervene," Radulovic said. "Five hours is a huge window to prevent this serious disorder." Past studies have tried to treat the extreme fear responses, after they have already developed, she noted.

The study, conducted with mice, was published Dec. 1 in the journal Biological Psychiatry.

An exaggerated fear disorder can be triggered by combat, an earthquake, a tsunami, rape or any traumatic psychological or physical event.

"People with this syndrome feel danger in everything that surrounds them," Radulovic said. "They are permanently alert and aroused because they expect something bad to happen. They have insomnia; their social and family bonds are severed or strained. They avoid many situations because they are afraid something bad will happen. Even the smallest cues that resemble the traumatic event will trigger a full-blown panic attack."

In a panic attack, a person's heart rate shoots up, they may gasp for breath, sweat profusely and have a feeling of impending death.

Many people bounce back to normal functioning after stressful or dangerous situations have passed. Others may develop an acute stress disorder that goes away after a short period of time. But some go on to develop post-traumatic stress syndrome, which can appear after a time lag.

The stage is set for post-traumatic stress disorder after a stressful event causes a natural flood of glutamate, a neurotransmitter that excites the neurons. The excess glutamate dissipates after 30 minutes, but the neurons remain frenzied. The reason is the glutamate interacts with a second protein (Homer1a), which continues to stimulate the glutamate receptor, even when glutamate is gone.

For the study, Northwestern scientists first subjected mice to a one-hour immobilization, which is distressing to them but not painful. Next, the mice explored the inside of a box and, after they perceived it as safe, received a brief electric shock. Usually after a brief shock in the box, the animals develop normal fear conditioning. If they are returned to the box, they will freeze in fear about 50 percent of the time. However, after the second stressful experience, these mice froze 80 to 90 percent of the time.

The animals' exaggerated chronic fear response continued for at least one month and resembles post-traumatic stress disorder in humans, Radulovic said.

For the second part of the study, Natalie Tronson, a postdoctoral fellow in Radulovic's Dunbar Laboratory for Research on Memory and Fear, and Radulovic repeated the two stressful experiences with the mice but then injected them with MPEP and MTEP five hours after the immobilization. This time the mice did not develop the exaggerated fear response and froze for only 50 percent of the time.

"The mice's fear responses were completely normal," Radulovic said. "Their memories of the stressful event didn't trigger the extreme responses anymore. This means we could have a prevention approach for humans exposed to acute, severe stressful events. "

INFORMATION:

The research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health.

END

New research at Rice University could ultimately show scientists the way to make batches of nanotubes of a single type.

A paper in the online journal Physical Review Letters unveils an elegant formula by Rice University physicist Boris Yakobson and his colleagues that defines the energy of a piece of graphene cut at any angle.

Yakobson, a professor in mechanical engineering and materials science and of chemistry, said this alone is significant because the way graphene handles energy depends upon the angle -- or chirality -- of its edge, and solving that process for ...

Investigators report no evidence of toxicity in the four hemophilia B patients enrolled to date in a gene therapy trial using a vector under development at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital and UCL (University College London) to correct the inherited bleeding disorder.

This trial was designed primarily as a safety test, with low and intermediate doses of the vector expected to produce little detectable Factor IX. The Factor IX protein helps the blood form clots. Individual with hemophilia B lack adequate levels of this clotting factor. The first participant in the ...

People with psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, are 12 times more likely to commit suicide than average, according to research released today by King's Health Partners.

The research found that the rate of suicide was highest in the first year following diagnosis (12 times national average) and that high risk persisted – remaining four times greater than the general population ten years after diagnosis, a time when there may be less intense clinical monitoring of risk.

Neither the risk of suicide nor the long-term risk of suicide, as compared ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. – It's illegal for businesses and law enforcement to profile a person based on their race, gender, or ethnicity, yet millions of Americans are being profiled every day based on their online consumer behavior and demographics.

Known as consumer profiling for behavioral advertising purposes, this type of profiling is largely unregulated.

The result, according to two recent articles in the journal of Computer Law & Security Review, is that consumers have less privacy and are being targeted by advertisers using increasingly sophisticated measures, which ...

It is supposed to be cool, colorless, tasteless and odorless. It may not have any pathogens or impair your health. This is the reason why drinking water is put to a whole series of screenings at regular intervals. Now, the AquaBioTox project will be added to create a system for constant real-time drinking water monitoring. At present, the tests required by the German Drinking Water Ordinance are limited to random samples that often only provide findings after hours and are always attuned to specific substances. In contrast, the heart of the AquaBioTox system is a bio-sensor ...

A gene that can cause congenital heart defects has been identified by a team of scientists, including a group from Princeton University. The discovery could lead to new treatments for those affected by the conditions brought on by the birth defect.

Princeton researchers focused on identifying and studying the gene in zebrafish embryos, and the team's work expanded to include collaborations with other groups studying the genetics of mice and people.

"This work really showcases the use of collaborative science and multiple model systems to better understand human disease," ...

AUGUSTA, Ga. – A drug prescribed for Parkinson's disease may also treat restless leg syndrome without the adverse side effects of current therapies, Medical College of Georgia researchers say.

Rasagaline works by prolonging the effect of dopamine, a chemical that transmits signals between nerve cells in the brain. The cause of RLS is unknown, but research suggests a dopamine imbalance. Parkinson's is caused by a dopamine insufficiency.

"The hope is that Rasagaline, because it prolongs the effect of existing dopamine, instead of producing more, will not come with adverse ...

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- Mayo Clinic researchers studied more than 200 children with epilepsy and found that even if the cause of focal-onset seizures cannot be identified and they do not fit into a known epilepsy syndrome, long-term prognosis is still excellent. This study was presented at the American Epilepsy Society's (http://www.aesnet.org/) annual meeting in San Antonio on Dec. 4.

Epilepsy (http://www.mayoclinic.org/epilepsy/) is a disorder characterized by the occurrence of two or more seizures. It affects almost 3 million Americans, and approximately 45,000 children ...

Cleveland - Scientists from South Korea, the United States and Japan analyzed fossil evidence found in South Korea and published research describing a new horned dinosaur. The newly identified genus, Koreaceratops hwaseongensis, lived about 103 million years ago during the late Early Cretaceous period. The specimen is the first ceratopsian dinosaur from the Korean peninsula. The partial skeleton includes a significant portion of the animal's backbone, hip bone, partial hind limbs and a nearly complete tail. Results from the analysis of the specimen were published in ...

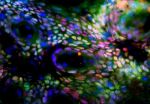

PHILADELPHIA - In a study published in the journal Developmental Cell, Sarah Millar PhD, professor of Dermatology and Cell & Developmental Biology at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, and colleagues demonstrate that a pair of enzymes called HDACs are critical to the proper formation of mammalian skin.

The findings, Millar says, not only provide information about the molecular processes underlying skin development, they also suggest a potential anticancer strategy. "Inhibition of these HDAC enzymes might be able to shut down the growth of tumors that ...