Age at surgery and valve type in PVR key determinants of re-intervention in congenital heart disease

Presentation at 95th AATS Annual Meeting indicates greater risk for younger and smaller children

2015-04-28

(Press-News.org) Over the last 15 years, survival of children with congenital heart disease (CHD) has greatly improved, so that currently there are more adults than children living with CHD. Consequently, people with CHD of all ages are undergoing pulmonary valve replacement (PVR) with bioprosthetic valves. In this retrospective review of all patients with CHD who underwent bioprosthetic PVR over an 18-year period at Boston Children's Hospital, investigators found that young age and small body weight predisposed patients toward re-intervention, as did the type of valve used.

Seattle, WA, April 28, 2015 -A retrospective review of 633 adults and children who underwent bioprosthetic pulmonary valve replacement (PVR) for congenital heart disease between 1996 and 2014 indicated that the risk of re-intervention was five times greater for children than adults, with the likelihood of re-intervention decreasing by 10% for each increasing year of age at surgery. Valve type was another important determinant of re-intervention, according to Rio S. Nomoto, BA, medical student at Tufts University School of Medicine, who will be presenting the results of this research at the 95th AATS Annual Meeting in Seattle on April 28.

PVR is recommended for both asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with CHD who have increased risk for right ventricular dilation and dysfunction. These patients may exhibit exercise intolerance, arrhythmia, and sudden cardiac events. Pulmonary regurgitation is a common indication for PVR.

"In this comprehensive series, we have identified specific valve type and all measures related to younger patient age at surgery to be important predictors of re-intervention," explained lead investigator Christopher W. Baird, MD, of the Department of Cardiac Surgery at Boston Children's Hospital of Harvard Medical School. The researchers also found that patients who were small for their age were much more likely to experience valve failure, suggesting that these children merit more intensive long-term follow-up.

In this group of 633 patients, the median age at surgery was 17.5 years and 49% of the patients were younger than 18 years. Eight patients were infants. Sixty-eight percent of cases had a diagnosis of Tetralogy of Fallot. The median follow-up was 2.9 years.

Six percent of patients (44) required re-intervention. Of these, 17 underwent a surgical re-intervention and 27 had cardiac catheterization to replace the pulmonary valve. Most events precipitating re-intervention happened at least three years after initial surgery. Thirty patients required more than one re-intervention and 19 deaths occurred post-operatively or during follow-up.

Age at surgery was an important predictor of future re-intervention. At five years post-op, the re-intervention rate was 11% for patients younger than 12 years, 7% for those 12-27 years old and 0% for those older than 27 years. At 10 years after surgery, 100% of children who had been operated on when they were less than 6 years old required repeat surgery as did 74% of those who had been between 6 and 11 years old; in contrast, the re-intervention rate was 22% for those age 12 to 17 years and 10% for those between 18 and 26 years old. None of the patients who were 27 years or older at the time of surgery required re-intervention at the 10-year mark, noted Ms. Nomoto.

Other factors associated with younger age were also found to be risk factors for re-intervention, such as low body weight, small body surface area, and body mass index. For instance, those younger than 20 years of age with BMI more than two standard deviations below normal were seven times more likely to experience valve failure. "Children with low BMI may merit closer monitoring following PVR or nutritional counseling to increase BMI prior to scheduling surgery," suggested Dr. Baird.

There was also a significant difference in the risk of re-intervention according to valve type. Fifty percent of patients received the Sorin Mitroflow, 35% the CE Magna or MagnaEase, 11% the CE Perimount and 4% porcine values. Of the 4 valves evaluated, the Sorin Mitroflow, exhibited a significantly higher re-intervention rate (17.6%) than the others (CE Magna/MagnaEase, 1.8%, CE Perimount, 0%, and porcine, 0%, p?0.01). Neither larger valve size nor BSA-adjusted valve orifice size predicted re-intervention. The investigators also found that the magnitude of the valve type differences was independent of age.

INFORMATION:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2015-04-28

Boston, Mass (April 27, 2015) -- In a recent issue of Science Translational Medicine, Brian Polizzotti, PhD, Bernhard Kuhn, MD, Sangita Choudhury, PhD, and colleagues affiliated with the Boston Children's Hospital's Translational Research Center report that the optimal window of time to stimulate heart muscle cell regeneration (cardiomyocyte proliferation) in humans is the first six months of life.

"Our results suggest that early administration of neuregulin may provide a targeted and multipronged approach to prevent heart failure in infants with CHD. Beginning treatment ...

2015-04-28

Humans and cattle share a similar epigenetic fetal overgrowth disorder that occurs more commonly following assisted reproduction procedures. In humans, this disorder is called Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (BWS), and in cattle it is called large offspring syndrome (LOS) and can result in the overgrowth of fetuses and enlarged babies. This naturally occurring, but rare syndrome can cause physical abnormalities in humans and cattle and often results in the deaths of newborn calves and birth-related injuries to their mothers.

Now, researchers at the University of Missouri ...

2015-04-28

CHESTER, Calif. - A study just published this week shows many bird species, including several of high conservation concern, aren't getting the habitat they need due to a focus on promoting California Spotted Owl habitat in the northern Sierra Nevada.

The study, published in the science journal, PLoS ONE, tracked different bird species' use of areas inside and outside Spotted Owl reserves for two years in Plumas and Lassen National Forests. The results show 17 species avoided the reserves, including species of conservation concern like Yellow Warblers and Olive-sided ...

2015-04-28

New Haven, Conn. -- Yale researchers conducted the first known randomized trial comparing three treatment strategies for opioid-dependent patients receiving emergency care. They found that patients given the medication buprenorphine were more likely to engage in addiction treatment and reduce their illicit opioid use.

Dependence on prescription and illicit opioids is an epidemic that continues to grow in the United States and globally. Drug overdoses account for more deaths each day than car crashes. "This is a huge public health problem," said first author Dr. Gail D'Onofrio, ...

2015-04-28

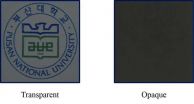

WASHINGTON, DC, April 28, 2015 -- The secret desire of urban daydreamers staring out their office windows at the sad brick walls of the building opposite them may soon be answered thanks to transparent light shutters developed by a group of researchers at Pusan National University in South Korea.

A novel liquid crystal technology allows displays to flip between transparent and opaque states -- hypothetically letting you switch your view in less than a millisecond from urban decay to the Chesapeake Bay. Their work appears this week in the journal AIP Advances, from AIP ...

2015-04-28

WASHINGTON, D.C., April 28, 2015--For couples struggling to conceive the old-fashioned way, in vitro fertilization (IVF) provides an alternate route to starting a family. When eggs are mixed with sperm in test tubes, the fertilized eggs to grow into embryos that can be implanted inside the uterus of a woman who will carry them to term.

IVF often works miracles for infertile couples, a fact for which its inventor won a Nobel Prize a few years ago. However, the procedure can be time-consuming, costly, and emotionally draining, often requiring multiple implantation cycles ...

2015-04-28

What happens when lithium-ion batteries overheat and explode has been tracked inside and out for the first time by a UCL-led team using sophisticated 3D imaging.

Understanding how Li-ion batteries fail and potentially cause a dangerous chain reaction of events is important for improving their design to make them safer to use and transport, say the scientists behind the study.

Hundreds of millions of these rechargeable batteries are manufactured and transported each year as they are integral to modern living, powering mobile phones, laptops, cars and planes. Although ...

2015-04-28

HANOVER, N.H. - Using an airborne imaging system for the first time in Antarctica, scientists have discovered a vast network of unfrozen salty groundwater that may support previously unknown microbial life deep under the coldest, driest desert on our planet. The findings shed new light on ancient climate change on Earth and provide strong evidence that a similar briny aquifer could support microscopic life on Mars.

The study appears in the journal Nature Communications. It is available through open access. A PDF of the study, photos and video also are available on request. ...

2015-04-28

PITTSBURGH, April 28, 2015 - African-Americans and Africans who swapped their typical diets for just two weeks similarly exchanged their respective risks of colon cancer as reflected by alterations of their gut bacteria, according to an international study led by researchers at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine published online today in Nature Communications.

Principal investigator Stephen O'Keefe, M.D., professor of medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Pitt School of Medicine, observed while practicing in South Africa that his ...

2015-04-28

KNOXVILLE--Many view Antarctica as a frozen wasteland. Turns out there are hidden interconnected lakes underneath its dry valleys that could sustain life and shed light on ancient climate change.

Jill Mikucki, a University of Tennessee, Knoxville, microbiology assistant professor, was part of a team that detected extensive salty groundwater networks in Antarctica using a novel airborne electromagnetic mapping sensor system called SkyTEM.

The research, funded by the National Science Foundation, provides compelling evidence that the underground lakes and brine-saturated ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Age at surgery and valve type in PVR key determinants of re-intervention in congenital heart disease

Presentation at 95th AATS Annual Meeting indicates greater risk for younger and smaller children