(Press-News.org) NEW YORK, NY (May 1, 2015) -- Bats are masters of flight in the night sky, capable of steep nosedives and sharp turns that put our best aircrafts to shame. Although the role of echolocation in bats' impressive midair maneuvering has been extensively studied, the contribution of touch has been largely overlooked. A study published April 30 in Cell Reports shows, for the first time, that a unique array of sensory receptors in the wing provides feedback to a bat during flight. The findings also suggest that neurons in the bat brain respond to incoming airflow and touch signals, triggering rapid adjustments in wing position to optimize flight control.

"This study provides evidence that the sense of touch plays a key role in the evolution of powered flight in mammals," says co-senior study author Ellen Lumpkin, a Columbia University associate professor of dermatology and physiology and cellular biophysics. "This research also lays the groundwork for understanding what sensory information bats use to perform such remarkable feats when flying through the air and catching insects. Humans cannot currently build aircrafts that match the agility of bats, so a better grasp of these processes could inspire new aircraft design and new sensors for monitoring airflow."

Bats must rapidly integrate different types of sensory information to catch insects and avoid obstacles while flying. The contribution of hearing and vision to bat flight is well established, but the role of touch has received little attention since the discovery of echolocation. Recently, co-senior study author Cynthia Moss and co-author Susanne Sterbing-D'Angelo of The Johns Hopkins University discovered that microscopic wing hairs stimulated by airflow, are critical for flight behaviors such as turning and controlling speed. But until now, it was not known how bats use tactile feedback from their wings to control flight behaviors.

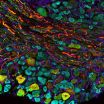

In the new study, the Lumpkin and Moss labs analyzed, for the first time, the distribution of different sensory receptors in the wing and the organization of the wing skin's connections to the nervous system. Compared to other mammalian limbs, the bat wing has a unique distribution of hair follicles and touch-sensitive receptors, and the spatial pattern of these receptors suggests that different parts of the wing are equipped to send different types of sensory information to the brain.

"While sensory cells located between the "fingers" could respond to skin stretch and changes in wind direction, another set of receptors associated with hairs could be specialized for detecting turbulent airflow during flight," says Sterbing-D'Angelo, who also holds an appointment at the University of Maryland.

Moreover, bat wings have a distinct sensory circuitry in comparison to other mammalian forelimbs. Sensory neurons on the wing send projections to a broader and lower section of the spinal cord, including much of the thoracic region. In other mammals, this region of the spinal cord usually receives signals from the trunk rather than the forelimbs. This unusual circuitry reflects the motley roots of the bat wing, which arises from the fusion of the forelimb, trunk, and hindlimb during embryonic development.

"This is important because it gives us insight into how evolutionary processes incorporate new body parts into the nervous system," says first author Kara Marshall of Columbia University. "Future studies are needed to determine whether these organizational principles of the sensory circuitry of the wing are conserved among flying mammals."

The researchers also found that neurons in the brain responded when the wing was either stimulated by air puffs or touched with a thin filament, suggesting that airflow and tactile stimulation activate common neural pathways.

"Our next steps will be following the sensory circuits in the wings all the way from the skin to the brain. In this study, we have identified individual components of these circuits, but next we would like to see how they are connected in the central nervous system," Moss says. "An even bigger goal will be to understand how the bat integrates sensory information from the many receptors in the wing to create smooth, nimble flight."

INFORMATION:

The paper is titled, "Somatosensory Substrates of Flight Control in Bats." The authors are Ellen A. Lumpkin, Kara L. Marshall, Mohit Chadha, Laura A. deSouza (CUMC); Susanne J. Sterbing-D'Angelo, Cynthia F. Moss (Johns Hopkins University).

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01NS073119), Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA95501210109), and other sources listed in the paper.

The other authors declare no financial or other conflicts of interest.

In proof-of-concept experiments, researchers at University of California, San Diego School of Medicine demonstrate the ability to tune medically relevant cell behaviors by manipulating a key hub in cell communication networks. The manipulation of this communication node, reported in this week's issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, makes it possible to reprogram large parts of a cell's signaling network instead of targeting only a single receptor or cell signaling pathway.

The potential clinical value of the basic science discovery is the ability ...

Dispersal and adaptation are two fundamental evolutionary strategies available to species given an environment. Generalists, like dandelions, send their offspring far and wide. Specialists, like alpine flowers, adapt to the conditions of a particular place.

Ecologists have typically modeled these two strategies, and the selective pressures that trigger them, by holding one strategy fixed and watching how the other evolves. New research published in the journal Evolution illustrates the dramatic interplay during the co-evolution of dispersal and adaptation strategies.

"This ...

WASHINGTON --An intervention in the emergency department designed to encourage tobacco cessation in smokers appears to be effective. Two and a half times more patients in the intervention group were tobacco-free three months after receiving interventions than those who did not receive the interventions, according to a study published online Friday in Annals of Emergency Medicine ( END ...

(BOSTON) -- If you opt to wear soft contact lenses, chances are you are using hydrogels on a daily basis. Made up of polymer chains that are able to absorb water, hydrogels used in contacts are flexible and allow oxygen to pass through the lenses, keeping eyes healthy.

Hydrogels can be up to 99 percent water and as a result are similar in composition to human tissues. They can take on a variety of forms and functions beyond that of contact lenses. By tuning their shape, physical properties and chemical composition and infusing them with cells, biomedical engineers have ...

Consumers can reduce the risk of Campylobacter food poisoning by up to 99.2% by using disinfectant wipes in the kitchen after preparing poultry. This is according to research published today (Friday 01 May) in the Society for Applied Microbiology's Journal of Applied Microbiology.

Dr Gerardo Lopez and his colleagues at the University of Arizona in the USA used antibacterial wipes on typical counter top materials - granite, laminate, and ceramic tile - to see if they reduce the risk of the cook and their family or guests ingesting harmful bacteria.

The results from Dr ...

Contrary to popular belief, more healthy kids' meals were ordered after a regional restaurant chain added more healthy options to its kids' menu and removed soda and fries, researchers from ChildObesity180 at Tufts University Friedman School reported today in the journal Obesity. Including more healthy options on the menu didn't hurt overall restaurant revenue, and may have even supported growth.

Researchers examined outcomes before and after the Silver Diner, a full-service family restaurant chain, made changes to its children's menu in order to make healthier items ...

New research has brought us closer to being able to understand the health benefits of coffee.

Monash researchers, in collaboration with Italian coffee roasting company Illycaffè, have conducted the most comprehensive study to date on how free radicals and antioxidants behave during every stage of the coffee brewing process, from intact bean to coffee brew.

The team observed the behaviour of free radicals - unstable molecules that seek electrons for stability and are known to cause cellular and DNA damage in the human body - in the coffee brewing process. For the ...

Researchers are a step closer to understanding the risk factors associated with endometriosis thanks to a new University of Adelaide study.

Dr Jonathan McGuane, from the University's Robinson Research Institute, says they discovered, for the first time, an association between contact with seminal fluid and the development of endometriosis.

"In laboratory studies, our research found that seminal fluid (a major component of semen) enhances the survival and growth of endometriosis lesions," says Dr McGuane, co-lead author on the paper.

Associate Professor Louise Hull, ...

Genome editing using CRISPR/Cas system has enabled direct modification of the mouse genome in fertilized mouse eggs, leading to rapid, convenient, and efficient one-step production of knockout mice without embryonic stem cells. In contrast to the ease of targeted gene deletion, the complementary application, called targeted gene cassette insertion or knock-in, in fertilized mouse eggs by CRISPR/Cas mediated genome editing still remains a tough challenge.

Professor Kohichi Tanaka and Dr. Tomomi Aida at Laboratory of Molecular Neuroscience, Medical Research Institute, TMDU ...

School and community gardens have become increasingly popular in recent years, but the people managing and working in these gardens are often unfamiliar with food safety practices that reduce the risk of foodborne illness. Now researchers have developed guidelines that address how to limit risk in these gardens - and a pilot study shows that the guidelines make a difference.

"People involved with these gardens are passionate about healthy eating, food security and helping people connect to where their food comes from," says Ashley Chaifetz, lead author of a paper describing ...