(Press-News.org) AMHERST, Mass. -- A revolution is coming in flexible electronic technologies as cheaper, more flexible, organic transistors come on the scene to replace expensive, rigid, silicone-based semiconductors, but not enough is known about how bending in these new thin-film electronic devices will affect their performance, say materials scientists at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

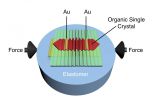

Writing in the current issue of Nature Communications, polymer scientists Alejandro Briseño and Alfred Crosby at UMass Amherst, with their doctoral student Marcos Reyes-Martinez, now a postdoctoral researcher at Princeton, report results of their recent investigation of how micro-scale wrinkling affects electrical performance in carbon-based, single-crystal semiconductors.

They are the first to apply inhomogeneous deformations, that is strain, to the conducting channel of an organic transistor and to understand the observed effects, says Reyes-Martinez, who conducted the series of experiments as part of his doctoral work.

As he explains, "This is relevant to today's tech industry because transistors drive the logic of all the consumer electronics we use. In the screen on your smart phone, for example, every little pixel that makes up the image is turned on and off by hundreds of thousands or even millions of miniaturized transistors."

"Traditionally, the transistors are rigid, made of an inorganic material such as silicon," he adds. "We're working with a crystalline semiconductor called rubrene, which is an organic, carbon-based material that has performance factors, such as charge-carrier mobility, surpassing those measured in amorphous silicon. Organic semiconductors are an interesting alternative to silicon because their properties can be tuned to make them easily processed, allowing them to coat a variety of surfaces, including soft substrates at relatively low temperatures. As a result, devices based on organic semiconductors are projected to be cheaper since they do not require high temperatures, clean rooms and expensive processing steps like silicon does."

Until now, Reyes-Martinez notes, most researchers have focused on controlling the detrimental effects of mechanical deformation to a transistor's electrical properties. But in their series of systematic experiments, the UMass Amherst team discovered that mechanical deformations only decrease performance under certain conditions, and actually can enhance or have no effect in other instances.

"Our goal was not only to show these effects, but to explain and understand them. What we've done is take advantage of the ordered structure of ultra-thin organic single crystals of rubrene to fabricate high-perfomance, thin-film transistors," he says. "This is the first time that anyone has carried out detailed fundamental work at these length scales with a single crystal."

Though single crystals were once thought to be too fragile for flexible applications, the UMass Amherst team found that crystals ranging in thickness from about 150 nanometers to 1 micrometer were thin enough to be wrinkled and applied to any elastomer substrate. Reyes-Martinez also notes, "Our experiments are especially important because they help scientists working on flexible electronic devices to determine performance limitations of new materials under extreme mechanical deformations, such as when electronic devices conform to skin."

They developed an analytical model based on plate bending theory to quantify the different local strains imposed on the transistor structure by the wrinkle deformations. Using their model they are able to predict how different deformations modulate charge mobility, which no one had quantified before, Reyes-Martinez notes.

These contributions "represent a significant step forward in structure-function relationships in organic semiconductors, critical for the development of the next generation of flexible electronic devices," the authors point out.

INFORMATION:

ALEXANDRIA, VA, MAY 5, 2015 -- A statistical analysis of Job Corps data strongly suggests positive average effects on wages for individuals who participated in the federal job-training program.

Results of the analysis recently were included in an article in the Journal of Business & Economic Statistics (http://www.tandfonline.com/toc/ubes20/current), a professional journal published by the American Statistical Association . The study was conducted by Xuan Chen of Renmin University of China and Carlos A. Flores of California Polytechnic State University.

Job Corps is ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- A 12-week dose of an investigational three-drug hepatitis C combination cleared the virus in 93 percent of patients with liver cirrhosis who hadn't previously been treated, according to a study in the May 5, 2015, issue of The Journal of the American Medical Association.

Bristol-Myers Squibb funded the trial of the combination of three drugs -- daclatasvir, asunaprevir, and beclabuvir. None of the three drugs are FDA-approved, but daclatasvir is currently under review by the FDA. Duke Medicine researchers collaborated on the design and analysis of the ...

In two studies appearing in the May 5 issue of JAMA, patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1 infection and with or without cirrhosis achieved high rates of sustained virologic response after 12 weeks of treatment with a combination of the direct-acting-antiviral drugs daclatasvir, asunaprevir, and beclabuvir.

Current estimates indicate that 130 million to 150 million people worldwide are chronically infected with HCV, resulting in up to 350,000 deaths per year. Of the 7 HCV genotypes identified, genotype 1 is the most prevalent worldwide, accounting for ...

Among patients with Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) who recovered following standard treatment with the antibiotics metronidazole or vancomycin, oral administration of spores of a strain of C difficile that does not produce toxins colonized the gastrointestinal tract and significantly reduced CDI recurrence, according to a study in the May 5 issue of JAMA.

C difficile is the cause of one of the most common and deadly health care-associated infections, linked to 29,000 U.S. deaths each year. Rates of CDI remain at unprecedented high levels in U.S. hospitals. Clinical ...

In what is a major step towards the prevention of recurring bouts of Clostridium difficile (Cdiff) infection, an international team led by Dale Gerding, MD, Hines Veterans Administration (VA) research physician and professor of Medicine at Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine, has shown that giving spores of non-toxic Cdiff by mouth is effective in stopping repeated bouts of Cdiff infection which occurs in 25-30 percent of patients who suffer an initial episode of diarrhea or colitis. The study is published in the May 5 issue of the Journal of American ...

For the first time, scientists have imaged thunder, visually capturing the sound waves created by artificially triggered lightning. Researchers from Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) are presenting the first images at a joint meeting of American and Canadian geophysical societies in Montreal, Canada, May 3-7.

"Lightning strikes the Earth more than 4 million times a day, yet the physics behind this violent process remain poorly understood," said Dr. Maher A. Dayeh, a research scientist in the SwRI Space Science and Engineering Division. "While we understand the general ...

Employing online training programs to teach psychotherapists how to use newer evidence-based treatments can be as successful as in-person instruction, according to a new RAND Corporation study.

Psychotherapy treatments can lag years behind what research has shown to be effective because there simply are not enough clinicians trained in new methods. That means that many people with mental health disorders are not getting the most effective nonpharmacological treatments, RAND researchers say.

For one such treatment, Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy to treat bipolar ...

Tropical Storm Noul is still threatening Yap Island located in the Caroline Islands of the western Pacific Ocean, and a part of the Federated States of Micronesia. Micronesia has posted a typhoon warning for the tiny island. The storm is currently 22 miles south-southwest of Ulithi (one of the outer islands of the State of Yap) and is moving west at 2 knots per hour. Maximum sustained winds for the storm is 55 knots gusting to 70 knots and maximum wave height is 20 feet.

Noul is moving to the west and is expected to veer west northwest and later to the northwest. ...

After gobbling the fourth Oreo in a row while bathed in refrigerator light, have you ever thought, "That wasn't enough," and then proceeded to search for something more?

Researchers at BYU have shed new light on why you, your friends, neighbors and most everyone you know tend to snack at night: some areas of the brain don't get the same "food high" in the evening.

In a newly published study, exercise sciences professors and a neuroscientist at BYU used MRI to measure how people's brains respond to high- and low-calorie food images at different times of the day. The ...

Anxiety disorders affect approximately one in six adult Americans, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. The most well-known of these include panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and social anxiety disorder. But what of brief bouts of anxiety caused by stressful social situations?

A new study by Tel Aviv University researchers, published recently in the Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, finds that anxiety experienced in social circumstances elevates the risk of bruxism - teeth grinding which causes tooth wear and ...