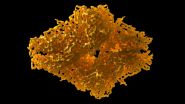

(Press-News.org) A new study shows that it is possible to use an imaging technique called cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to view, in near-atomic detail, the architecture of a metabolic enzyme bound to a drug that blocks its activity. This advance provides a new path for solving molecular structures that may revolutionize drug development, noted the researchers.

The protein imaged in this study was a small bacterial enzyme called beta-galactosidase; the drug to which it was bound is an inhibitor called phenylethyl-beta-D-thiogalactopyranoside (PETG), which fits into a pocket in the enzyme. Enzymes are typically proteins that act to catalyze biochemical reactions in the cell. Understanding what an enzyme looks like, both with and without a drug bound to it, allows scientists to design new drugs that can either block that enzyme's function (if the function is responsible for a disease), or enhance its activity (if lack of activity is causing a problem).

The study appeared online May 7, 2015, in Science Express. Sriram Subramaniam, Ph.D., of the National Cancer Institute's (NCI) Center for Cancer Research, led the research. NCI is part of the National Institutes of Health.

"This represents a new era in imaging of proteins in humans with immense implications for drug design," said NIH Director Francis S. Collins, M.D., Ph.D. "This near-atomic level of imaging provides detailed information about the keys that unlock cellular processes."

Drug development efforts often involve mapping contacts between small molecules and their binding sites on proteins. These mappings require the highest possible resolutions so that the shape of the protein chain can be traced and the hydrogen bonds between the protein and the small molecules it interacts with can be discerned.

In this study, the researchers were able to visualize beta-galactosidase at a resolution of 2.2 angstroms (or Å -- about a billionth of a meter in size), which is comparable to the level of detail that has thus far been obtained only by using X-ray crystallography. At these high resolutions, there is enough information in the structure to reliably assist drug design and development efforts.

To determine structures by cryo-EM, protein suspensions are flash-frozen at liquid nitrogen temperatures (-196°C to -210°C , or -320°F to -346°F) so the water around the protein molecules stays liquid-like. The suspensions are then imaged with electrons to obtain molecular images that are averaged together to discern a three-dimensional (3D) protein structure.

"The fact that cryo-EM technology allows us to image a relatively small protein at high resolution in a near-native environment, and knowing that the structure hasn't been changed by crystallization, that's a game-changer," said Dr. Subramaniam.

In the study, using about 40,000 molecular images, the researchers were able to compute a 2.2 Å resolution map of the structure of beta-galactosidase bound to PETG. This map not only allowed the researchers to determine the positioning of PETG in the binding pocket but also enabled them to pick out individual ions and water molecules within the structure and to visualize in great detail the arrangement of the amino acids that make up the protein.

Dr. Subramaniam and colleagues have recently used cryo-EM to understand the functioning of a variety of medically important molecular machines, such as the envelope glycoproteins on HIV and glutamate receptors found in brain cells. Their new finding, however, represents the highest resolution that they or others have achieved to date for a structure determined by cryo-EM.

"Cryo-EM is positioned to become an even more useful tool in structural biology and cancer drug development," said Douglas Lowy, M.D., acting director, NCI. "Even for proteins that are not amenable to crystallization, it could enable determination of their 3D structures at high resolution."

INFORMATION:

Reference: Bartesaghi, A., et al., 2015. 2.2 Angstrom resolution cryo-EM structure of beta-galactosidase in complex with a cell-permeant inhibitor. Science Express. Online May 7, 2015. DOI: http://www.sciencemag.org/lookup/doi/10.1126/science.aab1576.

The National Cancer Institute leads the National Cancer Program and the NIH's efforts to dramatically reduce the prevalence of cancer and improve the lives of cancer patients and their families, through research into prevention and cancer biology, the development of new interventions, and the training and mentoring of new researchers. For more information about cancer, please visit the NCI website at http://www.cancer.gov or call NCI's Cancer Information Service at 1-800-4-CANCER.

Messenger RNA (mRNA) levels dictate most differences protein levels in fast-growing cells when analyzed using statistical methods that account for noise in the data, according to a new study by researchers from the University of Chicago and Harvard University.

The research, published May 7, 2015 in the journal PLOS Genetics, counters widely reported studies arguing that the correlation between mRNA transcript levels and protein levels is relatively low, and that processes acting after mRNA transcription override mRNA levels. Instead, the authors argue, these conclusions ...

Boston, MA -- Researchers at Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health and the Broad Institute have identified a protein on the surface of human red blood cells that serves as an essential entry point for invasion by the malaria parasite. The presence of this protein, called CD55, was found to be critical to the Plasmodium falciparum parasite's ability to attach itself to the red blood cell surface during invasion. This discovery opens up a promising new avenue for the development of therapies to treat and prevent malaria.

"Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites have ...

Hereditary blindness caused by a progressive degeneration of the light-sensing cells in the eye, the photoreceptors, affects millions of people worldwide. Although the light-sensing cells are lost, cells in deeper layers of the retina, which normally cannot sense light, remain intact. A promising new therapeutic approach based on a technology termed "optogenetics" is to introduce light-sensing proteins into these surviving retinal cells, turning them into "replacement photoreceptors" and thereby restoring vision. However, several factors limit the feasibility of a clinical ...

PRINCETON, N.J.--The measles virus is known to cast a deadly shadow upon children by temporarily suppressing their immune systems. While this vulnerability was previously thought to have lasted a month or two, a new study shows that children may actually live in the immunological shadow of measles for up to three years - leaving them highly susceptible to a host of other deadly diseases.

Published in the journal Science, the study, led by researchers from Princeton University's Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs and Department of Ecology and Evolutionary ...

This news release is available in Spanish. Although the genetic blueprint of every cell is the same, each cell has the potential to become specific for a tissue or organ by controlling its gene expression. Thus, every cell "reads" or "switches on" a particular set of genes according to whether it should become a skin, heart, or liver cell. Launched by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 2010, the GTEx Project aims to create a reference database and tissue bank for scientists to study how genomic variants affect gene activity and disease susceptibility.

Following ...

CAMBRIDGE, Mass--Researchers have succeeded in creating a new "whispering gallery" effect for electrons in a sheet of graphene -- making it possible to precisely control a region that reflects electrons within the material. They say the accomplishment could provide a basic building block for new kinds of electronic lenses, as well as quantum-based devices that combine electronics and optics.

The new system uses a needle-like probe that forms the basis of present-day scanning tunneling microscopes (STM), enabling control of both the location and the size of the reflecting ...

For years, scientists have been puzzled by the presence of short stretches of genetic material floating inside a variety of cells, ranging from bacteria to mammals, including humans. These fragments are pieces of the genetic instructions cells use to make proteins, but are too short a length to serve their usual purpose. Reporting in this week's Cell, researchers at Rockefeller have discovered a major clue to the role these fragments play in the body -- and in the process, may have opened up a new frontier in the fight against breast cancer.

Specifically, Sohail Tavazoie ...

Every inch of our body, inside and out, is oozing with bacteria. In fact, the human body carries 10 times the number of bacterial cells as human cells. Many are our friends, helping us digest food and fight off infections, for instance. But much about these abundant organisms, upon which our life depends, remains mysterious. In research reported May 7 in Cell, scientists at Rockefeller finally crack the code of a fundamental process bacteria use to defend themselves against invaders.

For years, researchers have puzzled over conflicting results about the workings of a ...

EAST LANSING, Mich. - Much like a finger leaves its own unique print to help identify a person, researchers are now discovering that skull fractures leave certain signatures that can help investigators better determine what caused the injury.

Implications from the Michigan State University research could help with the determination of truth in child abuse cases, potentially resulting in very different outcomes.

Until now, multiple skull fractures meant several points of impact to the head and often were thought to suggest child abuse.

Roger Haut, a University Distinguished ...

PULLMAN, Wash.--Washington State University researchers say the popularity of bamboo landscaping could increase the spread of hantavirus, with the plant's prolific seed production creating a population boom among seed-eating deer mice that carry the disease.

Richard Mack, an ecologist in WSU's School of Biological Sciences, details how an outbreak could happen in a recent issue of the online journal PLOS One.

Bamboo plants are growing in popularity, judging by the increased number of species listed by the American Bamboo Society. Some grow in relatively self-contained ...