INFORMATION:

The National Computational Infrastructure, Australia, supported this work.

Solving corrosive ocean mystery reveals future climate

2015-05-11

(Press-News.org) Around 55 million years ago, an abrupt global warming event triggered a highly corrosive deep-water current through the North Atlantic Ocean. The current's origin puzzled scientists for a decade, but an international team of researchers has now discovered how it formed and the findings may have implications for the carbon dioxide emission sensitivity of today's climate.

The researchers explored the acidification of the ocean that occurred during a period known as the Paleocene Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), when the Earth warmed 9 degree Fahrenheit in response to a rapid rise in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and subsequently one of the largest-ever mass extinctions occurred in the deep ocean. They report their findings in today's (May 11) issue of Nature Geoscience.

This period closely resembles the scenario of global warming today.

"There has been a longstanding mystery about why ocean acidification caused by rising atmospheric carbon dioxide during the PETM was so much worse in the Atlantic compared to the rest of the world's oceans," said lead author Kaitlin Alexander, ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate System Science, University of New South Wales, Australia. "Our research suggests the shape of the ocean basins and changes to ocean currents played a key role in this difference. Understanding how this event occurred may help other researchers to better estimate the sensitivity of our climate to increasing carbon dioxide."

To get their results the researchers recreated the ocean basins and land masses of 55 million years ago in a global climate model.

During that time a ridge on the ocean floor existed between the North and South Atlantic that separated the deep water in the North Atlantic from the rest of the world's oceans. The ridge was like a giant bathtub on the ocean floor.

The simulations showed this ridge became filled with extremely corrosive water from the Arctic Ocean, which mixed with dense salty water from the Tethys Ocean and sank to the seafloor, where it accumulated. The sediment in this area indicates the water was so corrosive that it dissolved all the calcium carbonate produced by organisms that settled on the ocean floor.

When the Earth warmed as a result of a rapid increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide, it eventually warmed this corrosive bottom water. As this water warmed it became less dense and denser water sinking from above replaced it. The corrosive deep water was pushed up and spilled over the edge of the giant "bathtub" and flowed into the South Atlantic.

"That corrosive water spread south through the Atlantic, then east into the Southern Ocean and eventually made its way to the Pacific," said Tim Bralower, professor of geosciences, Penn State. "The pattern of the event corresponds very closely to what the sediment records tell us. Those records show almost 100 percent dissolution of calcium carbonate in the South Atlantic sediment."

Determining how the event occurred also has important implications for today's climate and how it might warm in response to increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide.

If the high amount of acidification in the Atlantic Ocean was an indication of global acidification, then it would suggest enormous amounts of carbon dioxide are necessary to increase temperatures by 9 degrees Fahrenheit. However, these latest findings suggest that other factors made the Atlantic bottom water more corrosive than in other ocean basins.

"We now understand why the dissolution of sediments in the Atlantic Ocean was different from records in other ocean basins," said Katrin Meissner, associate professor, Climate Change Research Centre, University of New South Wales. "Using all sediments combined we can now estimate that the amount of greenhouse gases released into the atmosphere causing a temperature rise of 5°C (9 degrees Fahrenheit), was around the carbon dioxide equivalent of 7,000 to10,000 gigatons of carbon. This is similar to the amount of carbon available in fossil fuel reservoirs today."

The big difference between the PETM and the alteration to the current climate is the speed of the change, said Alexander.

"Today we are emitting carbon dioxide into the atmosphere ten times faster than the rate of natural carbon dioxide emissions during the PETM," said Alexander. "If we continue as we are, we will see the same temperature increase that took a few thousand years during the PETM occur in just a few hundred years. This is an order of magnitude faster and likely to have profound impacts on the climate system."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Noul makes landfall in Philippines, thousands flee

2015-05-11

On Sunday, May 10, 2015, Super Typhoon Noul (designated Dodong in the Philippines) made landfall in Santa Ana, a coastal town in Cagayan on the northeastern tip of the Philippine Islands. Close to 2,500 residents evacuated as the storm crossed over, and as of today no major damage or injuries have been reported. Trees were downed by the high winds and power outages occurred during the storm. Noul is expected to weaken now that it has made land, and to move faster as it rides strong surrounding winds. It is forecast to completely leave the Philippines by Tuesday morning ...

Ana makes landfall in South Carolina on Mother's Day

2015-05-11

This was no Mother's Day gift to South Carolina as Ana made landfall on Sunday. Just before 6 am, Ana made landfall north of Myrtle Beach, SC with sustained winds of 45 mph, lower than the 50 mph winds it was packing as a tropical storm over the Atlantic. After making landfall, Ana transitioned to a tropical depression and is currently moving northward through North Carolina and will continue its trek northward. Heavy rain and storm surges are expected in the storm's wake. Storms of this size will create dangerous rip currents so beachgoers should be wary of Ana as ...

Tropical Storm Dolphin threatening Micronesia

2015-05-11

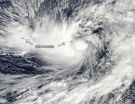

The MODIS instrument on the Aqua satellite captured this image of Tropical Storm Dolphin riding roughshod over the Federated States of Micronesia. Dolphin strengthened to tropical storm status between Bulletin 272 and 273 (1620 GMT and 2200 GMT) of the Joint Typhoon Weather Center on May 09, 2015.

The AIRS instrument on Aqua captured the images below of Dolphin between 10:59 pm EDT on May 9 and 11:00 am May 10 (02:59 UTC/15:17 UTC).

Dolphin is currently located (as of 5:00am EDT/0900 GMT) 464 miles ENE of Chuuk moving northwest at 9 knots (10 mph). It is expected ...

Ethicists propose solution for US organ shortage crisis in JAMA piece

2015-05-11

New York, NY - The United States has a serious shortage of organs for transplants, resulting in unnecessary deaths every day. However, a fairly simple and ethical change in policy would greatly expand the nation's organ pool while respecting autonomy, choice, and vulnerability of a deceased's family or authorized caregiver, according to medical ethicists and an emergency physician at NYU Langone Medical Center.

The authors share their views in a new article in the May 11 online edition of the Journal of American Medical Association's "Viewpoint" section.

"The U.S. ...

Starved T cells allow hepatitis B to silently infect liver

2015-05-11

Hepatitis B stimulates processes that deprive the body's immune cells of key nutrients that they need to function, finds new UCL-led research funded by the Medical Research Council and Wellcome Trust.

The work helps to explain why the immune system cannot control hepatitis B virus infection once it becomes established in the liver, and offers a target for potential curative treatments down the line. The research also offers insights into controlling the immune system, which could be useful for organ transplantation and treating auto-immune diseases.

Worldwide 240 million ...

For biofuels and climate, location matters

2015-05-11

A new study published in the journal Nature Climate Change shows that, when looking at the production site alone, growing biofuel crops can have a significant impact on climate depending on location and crop type. The study is the first geographically explicit life cycle assessment to consider the full range of greenhouse gases emissions from vegetation and soil carbon stock to nitrogen fertilizer emissions in all locations in the world.

In the last couple of years, research has begun to raise questions about the sustainability of biofuels. Life cycle assessments--a method ...

Harmful algal blooms in the Chesapeake Bay are becoming more frequent

2015-05-11

CAMBRIDGE, MD (May 11, 2015)--A recent study of harmful algal blooms in the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries by the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science show a marked increase in these ecosystem-disrupting events in the past 20 years that are being fed by excess nitrogen runoff from the watershed. While algal blooms have long been of concern, this study is the first to document their increased frequency in the Bay and is a warning that more work is needed to reduce nutrient pollution entering the Bay's waters.

The Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries ...

Robot pets to rise in an overpopulated world

2015-05-11

University of Melbourne animal welfare researcher Dr Jean-Loup Rault says the prospect of robopets and virtual pets is not as far-fetched as we may think.

His paper in the latest edition of Frontiers in Veterinary Science argues pets will soon become a luxury in an overpopulated world and the future may lie in chips and circuits that mimic the real thing.

"It might sound surreal for us to have robotic or virtual pets, but it could be totally normal for the next generation," Dr Rault said.

"It's not a question of centuries from now. If 10 billion human beings live ...

Toddlers understand sound they make influences others, research shows

2015-05-11

ATLANTA--Confirming what many parents already know, researchers at Georgia State University and the University of Washington have discovered that toddlers, especially those with siblings, understand how the sounds they make affect people around them.

The findings are published in the Journal of Cognition and Development.

There has been limited research on what children understand about what others hear, with previous studies focusing only on whether a sound could be heard. This study takes a new approach to learning what children understand about sound by introducing ...

A climate signal in the global distribution of copper deposits

2015-05-11

ANN ARBOR--Climate helps drive the erosion process that exposes economically valuable copper deposits and shapes the pattern of their global distribution, according to a new study from researchers at the University of Idaho and the University of Michigan.

Nearly three-quarters of the world's copper production comes from large deposits that form about 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) beneath the Earth's surface, known as porphyry copper deposits. Over the course of millions to tens of millions of years, they are exposed by erosion and can then be mined.

Brian Yanites of the ...