(Press-News.org) URBANA, Ill -- Wetlands created 20 years ago between tile-drained agricultural fields and the Embarras River were recently revisited for a new two-year University of Illinois research project. Results show an overall 62 percent nitrate removal rate and little emission of nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas.

"Slowing down the rate of flow of the water by intercepting it in the wetland is what helps to remove the nitrate," says Mark David, a University of Illinois biogeochemist in the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences. "The vegetation that grows in the wetland doesn't make much of a difference because the grasses don't take up much nitrogen. It's just about slowing the water down and allowing the microbes in the sediment to eliminate the nitrate. It goes back into the air as harmless nitrogen gas."

David was involved with research on these same wetlands from 1994-98 but didn't take any measurements after that. He has spent much of his career studying the runoff from tile-drained fields and methods to reduce losses of nitrate and phosphorus. The runoff, particularly nitrate, from fields in the upper Mississippi River basin, is believed to be the major cause of the hypoxia in the Gulf of Mexico.

"The USDA requested proposals on the effectiveness of wetlands and woodchip bioreactors to reduce nitrate losses from fields, but was also concerned about greenhouse gas emissions," says David. Working with graduate student and lead author Tyler Groh, "We found the greenhouse gas emissions were really quite low. Nitrous oxide was not a problem. The other good news is that this research confirms that wetlands really do work to reduce nitrate runoff, and they work long term."

David says that, along with fertilizer management, cover crops, and bioreactors, wetlands are an integral part of the Illinois Nutrient Loss Reduction Strategy. Building a wetland costs about the same as installing a bioreactor.

One of the reasons David prefers wetlands to help solve the nitrogen pollution problem is that they work reasonably well in the winter when the water temperatures are low.

What's the drawback?

"Farmland along the river may be flood prone, but depending upon the landscape, it could be farmable land," says Lowell Gentry, senior research specialist and co-principal investigator on the project. "In this case, it was pasture so the wetlands didn't reduce the row-crop acreage, and the landowner was able to use it as hunting grounds. Our project included funds to build new wetlands, but we couldn't convince anyone to do it. Wetlands have been a hard sell.

"Farmers generally prefer to install bioreactors because they don't take up much space," Gentry says. "A wetland requires about 3 to 4 percent of the drainage area. So, for a 100-acre field, you'd need about 4 acres in wetland. Although bioreactors don't use much land, they also don't slow the water enough during high flows. Research on their performance is still underway. Because water tends to be in the wetlands for a much longer time period, they are more effective."

David says there has been a push from environmental groups for years to build more wetlands to help lower the nitrate levels. There are a few in the Lake Bloomington watershed but not in the Embarras River watershed, even after all this time.

"No one wants to mandate a certain practice -- wetlands, bioreactors, cover crops, adjusting the timing of applying fertilizer-all of these things that we know help reduce nutrient loss," says David. "But, because of this research, we know that wetlands are a long-term nitrate removal method that keeps on working with little greenhouse gas emission. By building a wetland, farmers have an opportunity to make a substantial nitrate reduction in the transport of nitrate from their fields to the Gulf."

INFORMATION:

"Nitrogen removal and greenhouse gas emissions from constructed wetlands receiving tile drainage water" is published in the Journal of Environmental Quality. The research was conducted by Tyler Groh, Lowell Gentry, and Mark David. It was partially funded by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

The act of identifying a perpetrator does not just involve memory and thinking, but also constitutes a moral decision. This is because, by the act of identifying or not identifying someone, the eyewitness runs the risk of either convicting an innocent person or letting a guilty person go free.

In an article published recently in Archives of Scientific Psychology, Spring et al. (2015) discuss two studies in which children and adolescents of different ages watched a film involving a potential wrong-doing: throwing a lit birthday cake into a wastebasket, either with or without ...

A new study published today in the journal Addiction has compiled the best, most up-to-date evidence on addictive disorders globally. It shows that almost 5% of the world's adult population (240 million people) have an alcohol use disorder and more than 20% (1 billion people) smoke tobacco. Getting good data on other drugs such as heroin and cannabis is much more difficult but for comparison the number of people injecting drugs is estimated at around 15 million worldwide.

The "Global Statistics on Addictive Behaviours: 2014 Status Report" goes further in showing that ...

BUFFALO, N.Y. -- Tinnitus is the most common service-related disability for veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. Often described as a ringing in the ears, more than 1.5 million former service members, one out of every two combat veterans, report having this sometimes debilitating condition, resulting in more than $2 billion dollars in annual disability payments by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Tinnitus is largely a mystery, a phantom sound heard in the absence of actual sound. Tinnitus patients "hear" ringing, buzzing or hissing in their ears much like ...

Transgenic Huntington's disease monkeys show similarity to humans with Huntington's in their progressive neurodegeneration and decline of motor control, scientists from Yerkes National Primate Research Center, Emory University, report.

These findings are promising for developing a preclinical, large animal model of Huntington's disease for assessing new therapeutics, which could ultimately provide better treatment options, including altering the course of the disease.

In this first multiyear study on a transgenic nonhuman primate model for Huntington's, lead author ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- Lemur girls behave more like the guys, thanks to a little testosterone, according to a new study.

Males rule in most of the animal world. But when it comes to conventional gender roles, lemurs -- distant primate cousins of ours -- buck the trend.

It's not uncommon for lady lemurs to bite their mates, snatch a piece of fruit from their hands, whack them in the head or shove them out of prime sleeping spots. Females mark their territories with distinctive scents just as often as the males do. Males often don't take their share of a meal until the females ...

BROOKLYN, New York -- Researchers have demonstrated a new metal matrix composite that is so light that it can float on water. A boat made of such lightweight composites will not sink despite damage to its structure. The new material also promises to improve automotive fuel economy because it combines light weight with heat resistance.

Although syntactic foams have been around for many years, this is the first development of a lightweight metal matrix syntactic foam. It is the work of a team of researchers from Deep Springs Technology (DST) and the New York University ...

The sun was just beginning to rise as two men headed down to the beach to board a small inflatable boat. Searching for abalone was on their agenda for the day. Their excitement was difficult to contain as they surveyed the coastline looking for sand ridges -- an important clue that abalone may be near. The two men, David Witting and Bill Hagey, share a passion for finding the now rare white abalone and understanding the movement and feeding behaviors of all abalone species.

David Witting, a NOAA Fisheries biologist, has been engaged in efforts to restore abalone populations ...

Many of us are familiar with electrolytic splitting of water from their school days: if you hold two electrodes into an aqueous electrolyte and apply a sufficient voltage, gas bubbles of hydrogen and oxygen are formed. If this voltage is generated by sunlight in a solar cell, then you could store solar energy by generating hydrogen gas.This is because hydrogen is a versatile medium of storing and using "chemical energy". Research teams all over the world are therefore working hard to develop compact, robust, and cost-effective systems that can accomplish this challenge. ...

For the first time, a researcher at the University of Waterloo has theoretically demonstrated that it is possible to detect a single nuclear spin at room temperature, which could pave the way for new approaches to medical diagnostics.

Published in the journal Nature nanotechnology this week, Amir Yacoby from the University of Waterloo, along with colleagues from University of Basel and RWTH Aachen University, propose a theoretical scheme that could lead to enhanced Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) imaging of biological materials in the near future by using weak magnetic ...

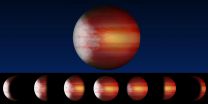

TORONTO, ON -- "Cloudy for the morning, turning to clear with scorching heat in the afternoon."

While this might describe a typical late-summer day in many places on Earth, it may also apply to planets outside our solar system, according to a new study by an international team of astrophysicists from the University of Toronto, York University and Queen's University Belfast.

Using sensitive observations from the Kepler space telescope, the researchers have uncovered evidence of daily weather cycles on six extra-solar planets seen to exhibit different phases. Such phase ...