(Press-News.org) In a letter to the Medical Journal of Australia published today, a Monash University-led team is asking for hepatitis C virus patients to gain improved access to drugs to prevent liver related deaths.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a major public health burden in Australia, with estimates of 230,000 people chronically infected.

The research team are calling for the government to subsidise a new therapy which has high cure rates, known as direct acting antiviral (DAA) therapy.

Monash University Professor William Sievert said a delay in access to DAA treatment means that thousands of HCV infected patients could die or develop advanced liver disease.

"If we delay just one year, there will be an extra 900 liver related deaths, 800 new cases of cirrhosis and 500 new cases of liver cancer. These staggering numbers double if we wait for two years," he said.

"During this decade, the therapy should become the norm for the HCV-infected population. However, the high cost of DAA regimens and competing public health priorities may limit the potential impact of new HCV therapies."

Currently, the cost of DAA treatment is out of reach for most HCV patients.

"The large number of liver-related deaths every year caused by HCV places an enormous burden on our health system," said Professor Sievert, Department of Medicine at Monash Medical Centre.

"Our research team modelled how the HCV disease burden and associated health care costs in Australia will increase as the infected population ages."

The team demonstrated that increasing the efficacy of antiviral therapy and the number of patients treated could avert the expected increase in HCV liver related deaths and end stage liver disease.

Professor Sievert's team examined the impact of delayed access to DAA treatment by modelling one and two year delays.

"We estimate that if the current treatment regimens continue in Australia, there will be approximately 22,200 liver related deaths between 2014 and 2030," said Professor Sievert.

"However, if DAA treatment is made widely available and accessible through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), that number of deaths will decrease to 13,500 in the same time period."

"We believe it is critical to provide patients with access to highly effective treatment to cure HCV infection without delay in order to diminish future HCV-related morbidity and mortality," added Professor Sievert.

INFORMATION:

Washington, DC (May 18, 2015) -- Patients faced with a choice of surgical options want to engage their physicians and take a more active role in decision-making, according to a study (abstract 567) released at Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) 2015. Further, those physicians must provide better support tools to help patients participate in the decision-making process. The study found that patients consult multiple sources (Internet, family, friends, doctors, etc.) and say that while doctors provide the most believable information, it was also the least helpful.

"In this ...

The historical past is important when we seek to understand environmental conditions as they are today and predict how these might change in the future. This is according to researchers from Umeå University, whose analyses of lake-sediment records show how lake-water carbon concentrations have varied depending on long-term natural dynamics over thousands of years, but also in response to human impacts over the past several hundred years. The study has been published in PNAS (the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences).

Environmental monitoring programmes ...

Just as alchemists always dreamed of turning common metal into gold, their 19th century physicist counterparts dreamed of efficiently turning heat into electricity, a field called thermoelectrics. Such scientists had long known that in conducting materials the flow of energy in the form of heat is accompanied by a flow of electrons. What they did not know at the time is that it takes nanometric-scale systems for the flow of charge and heat to reach a level of efficiency that cannot be achieved with larger scale systems. Now, in a paper published in EPJ B Barbara Szukiewicz ...

The grounding of a giant iceberg in Antarctica has provided a unique real-life experiment that has revealed the vulnerability of marine ecosystems to sudden changes in sea-ice cover.

UNSW Australia scientists have found that within just three years of the iceberg becoming stuck in Commonwealth Bay - an event which dramatically increased sea-ice cover in the bay - almost all of the seaweed on the sea floor had decomposed, or become discoloured or bleached due to lack of light.

"Understanding the ecological effect of changes in sea-ice is vital for understanding the future ...

Scientists are attempting to mimic the memory and learning functions of neurons found in the human brain. To do so, they investigated the electronic equivalent of the synapse, the bridge, making it possible for neurons to communicate with each other. Specifically, they rely on an electronic circuit simulating neural networks using memory resistors. Such devices, dubbed memristor, are well-suited to the task because they display a resistance, which depends on their past states, thus producing a kind of electronic memory. Hui Zhao from Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications, ...

An international team of scientists have discovered a new species of typhlogammarid amphipod in the limestone karstic caves of Chjalta mountain range -- the southern foothills of the Greater Caucasus Range. The study was published in the open access journal Subterranean Biology.

The new amphipod, which belongs to the genus Zenkevitchia, is the second species known from this group. This new addition to the genus is named Zenkevitchia yakovi after the famous Russian biospeleologist Prof Yakov Birstein.

Typhlogammarid amphipods are a group blind and unpigmented endemic ...

Radiotherapy used in cancer treatment is a promising treatment method, albeit rather indiscriminate. Indeed, it affects neighbouring healthy tissues and tumours alike. Researchers have thus been exploring the possibilities of using various radio-sensitizers; these nanoscale entities focus the destructive effects of radiotherapy more specifically on tumour cells. In a study published in EPJ D, physicists have now shown that the production of low-energy electrons by radio-sensitizers made of carbon nanostructures hinges on a key physical mechanism referred to as plasmons ...

This news release is available in German.

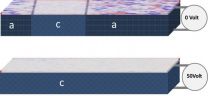

Scientists from Paris and Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin have been able to switch ferromagnetic domains on and off with low voltage in a structure made of two different ferroic materials. The switching works slightly above room temperature. Their results, which are published online in Scientific Reports, might inspire future applications in low-power spintronics, for instance for fast and efficient data storage.

Information can be written as a sequence of bit digits, i.e. "0" and "1". Materials which display ferromagnetism ...

Bowel cancer is often driven by mutations in one of several different genes, and a patient can have a cancer with a different genetic make-up to another patient's cancer. Identifying the molecular alterations involved in each patient's cancer enables doctors to choose drugs that best target specific alterations.

However, it is also becoming clear that while some cancers may be driven by a single gene mutation, individual tumours are often composed of groups of cancer cells, with each group having different molecular alterations from the others. This is known as intra-tumour ...

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a major human pathogen and is known to be associated with increased risk of fatal heart complications including heart failure and heart attacks.

As Streptococcus pneumoniae is a respiratory pathogen that does not infect the heart, however, this association with heart problems has puzzled clinicians and researchers, particularly as even prompt use of antibiotics does not provide any protection from cardiac complications.

A multidisciplinary research team, led by Professor Aras Kadioglu and Professor Cheng-Hock Toh at the University of Liverpool, ...