(Press-News.org) Bacteria that live in the guts of cicadas have split into many separate but interdependent species in a strange evolutionary phenomenon that leaves them reliant on a bloated genome, a new paper by CIFAR Fellow John McCutcheon's lab (University of Montana) has found.

Cicadas subsist on tree sap, which doesn't provide them all the nutrients they need to live. Bacteria in their gut, including one called Hodgkinia, turns the sap into amino acids that sustain them during their unusual lives. Cicadas spend most of their lives underground before emerging in droves, singing loudly, mating for weeks and then dying off en masse. McCutcheon studied the evolution of Hodgkinia in Magicicada tredicim, a type of cicada that burrows for 13 years. He dissected the insects and removed the bacteria, then sequenced their DNA.

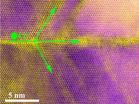

What he found, shortly after setting up his own lab several years ago, perplexed him so much that he thought there was a technical mistake. "I could not make heads or tails of it," McCutcheon says. "It looked so, so broken." Hodgkinia's genome was a fragmented and overlapping mess that seemed to contain many copies of its DNA with slight variations.

He set it aside for a while, until last year, when he found that in the gut of a South American cicada with a much shorter life span, Hodgkinia had split into two separate species about five million years ago. The split left the insect reliant on double the species to create the same nutrients that required only one species to make before.

When McCutcheon's lab returned to the 13-year cicada, they found many more than two splits. Pulling apart the web of genetic information revealed the bacterium's genome had increased about 10-fold from what the scientists estimate its ancestor's DNA looked like. They found at least 17 new chromosomes or genomes, but estimate that the cicada may rely on as many as 50 to survive.

"We think Hodgkinia has a very high mutation rate," McCutcheon says. "It makes a lot of mistakes every replication cycle."

In cicadas with longer lives, those mistakes might be piling up during idle years spent underground, leading to broken genes in different cell types. McCutcheon's lab is now studying how a growing symbiont might make life difficult for cicadas. McCutcheon compares the problem with trying to care for many children -- several species of Hodgkinia -- in addition to its other symbiont, a bacterium called Sulcia.

"We can actually see a little bit of evidence for that in our data, where the tissue volume the cicada puts toward one of its children, Sulcia, is getting smaller, because of the increasing space it must devote to its growing gaggle of Hodgkinia. It's trying to accommodate all these different cell types," he says.

From a broader perspective, understanding how symbioses evolve over time could help scientists learn more about organelles such as mitochondria, which humans and all other animals depend on.

"The greater context of this is something that people in Integrated Microbial Biodiversity and CIFAR have been thinking about for a long time," McCutcheon says.

They've been studying questions such as why some organelle genomes look very different than others, and how genetic complexity arises from evolution that isn't adaptive, or beneficial to the organism. "There is no better place in the world than CIFAR to think about these fundamental and broad themes in biology," McCutcheon says.

The paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences was published in conjunction with a Sackler Colloquium co-sponsored by CIFAR and the US National Academy of Sciences, entitled "Symbioses Becoming Permanent: The Origins and Evolutionary Trajectories of Organelles."

INFORMATION:

Contacts:

Lindsay Jolivet

Writer & Media Relations Specialist

Canadian Institute for Advanced Research

lindsay.jolivet@cifar.ca

(416) 971-4871

John McCutcheon

CIFAR Associate Fellow

University of Montana

john.mccutcheon@umontana.edu

(406) 243-6071

The sight of skilful aerial manoeuvring by flocks of Greylag geese to avoid collisions with York's Millennium Bridge intrigued mathematical biologist Dr Jamie Wood. It raised the question of how birds collectively negotiate man-made obstacles such as wind turbines which lie in their flight paths.

It led to a research project with colleagues in the Departments of Biology and Mathematics at York and scientists at the Animal and Plant Health Agency. The study found that the social structure of groups of migratory birds may have a significant effect on their vulnerability ...

Most people see defects as flaws. A few Michigan Technological University researchers, however, see them as opportunities. Twin boundaries -- which are small, symmetrical defects in materials -- may present an opportunity to improve lithium-ion batteries. The twin boundary defects act as energy highways and could help get better performance out of the batteries.

This finding, published in Nano Letters earlier this year, turns a previously held notion of material defects on its head. Reza Shahbazian-Yassar helped lead the study and holds a joint appointment at Michigan ...

May 21, 2015 -- A technique called auditory brainstem implantation can restore hearing for patients who can't benefit from cochlear implants. A team of US and Japanese experts has mapped out the surgical anatomy and approaches for auditory brainstem implantation in the June issue of Operative Neurosurgery, published on behalf of the Congress of Neurological Surgeons by Wolters Kluwer.

Dr. Albert L. Rhoton, Jr., and colleagues of University of Florida, Gainesville, and Fukuoka University, Japan, performed a series of meticulous dissections to demonstrate and illustrate ...

Water behaves in mysterious ways. Especially below zero, where it is dubbed supercooled water, before it turns into ice. Physicists have recently observed the spontaneous first steps of the ice formation process, as tiny crystal clusters as small as 15 molecules start to exhibit the recognisable structural pattern of crystalline ice. This is part of a new study, which shows that liquid water does not become completely unstable as it becomes supercooled, prior to turning into ice crystals. The team reached this conclusion by proving that an energy barrier for crystal formation ...

New research shows that infections can impair your cognitive ability measured on an IQ scale. The study is the largest of its kind to date, and it shows a clear correlation between infection levels and impaired cognition.

Anyone can suffer from an infection, for example in their stomach, urinary tract or skin. However, a new Danish study shows that a patient's distress does not necessarily end once the infection has been treated. In fact, ensuing infections can affect your cognitive ability measured by an IQ test:

"Our research shows a correlation between hospitalisation ...

This news release is available in German. FRANKFURT. In laboratory tests, two out of ten teethers, plastic toys used to sooth babies' teething ache, release endocrine disrupting chemicals. One product contains parabens, which are normally used as preservatives in cosmetics, while the second contains six so-far unidentified endocrine disruptors. The findings were reported by researchers at the Goethe University in the current issue of the Journal of Applied Toxicology.

"The good news is that most of the teethers we analyzed did not contain any endocrine disrupting ...

Computer simulations have predicted a new phase of matter: atomically thin two-dimensional liquid.

This prediction pushes the boundaries of possible phases of materials further than ever before. Two-dimensional materials themselves were considered impossible until the discovery of graphene around ten years ago. However, they have been observed only in the solid phase, because the thermal atomic motion required for molten materials easily breaks the thin and fragile membrane. Therefore, the possible existence of an atomically thin flat liquid was considered impossible.

Now ...

Scientists and clinicians on the Norwich Research Park have carried out the first detailed study of how our intestinal tract changes as we age, and how this determines our overall health.

As well as digesting food, the gut plays a central role in programming our immune system, and provides an effective barrier to bacteria that could make us ill. In particular, immune cells that line the gut work to maintain the integrity of the barrier, as well as maintaining a balance that provides a healthy environment for beneficial bacteria, but reacts to combat invasion by pathogenic ...

Face perception plays an important role in social communication. There have been many studies of face perception in human using non-invasive neuroimaging and electrophysiological methods, but studies of face perception in children were quite limited. Here, a Japanese research team led by Dr. Miki Kensuke and Prof Ryusuke Kakigi, in the National Institute for Physiological Sciences, National Institutes of Natural Sciences, investigated the development of face perception in Japanese children, by using an electroencephalogram (EEG). The team also compared their results for ...

Qatar's capital city, Doha, is set to emerge as a major knowledge hub, with its educated, high-tech workforce and its international connectivity. However, the lack of a cohesive plan for development and the mobility of that workforce in and out of Qatar could stymie its success on the global stage.

The rulers of the Arab state of Qatar have shaped their capital city, Doha, into one of the fastest-growing cities in the world and also, through economic diversification and other measures, establishing it as a significant hub city in the global knowledge economy. Research ...