(Press-News.org) WASHINGTON, D.C. - In northwestern Greenland, glaciers flow from the main ice sheet to the ocean in see-sawing seasonal patterns. The ice generally flows faster in the summer than in winter, and the ends of glaciers, jutting out into the ocean, also advance and retreat with the seasons.

Now, a new analysis shows some important connections between these seasonal patterns, sea ice cover and longer-term trends. Glaciologists hope the findings, accepted for publication in the June issue of the American Geophysical Union's Journal of Geophysical Research-Earth Surface and available online now, will help them better anticipate how a warming Greenland will contribute to sea level rise.

"Rising sea level can be hard on coastal communities, with higher storm surges, greater flooding and saltwater encroachment on freshwater," said lead author Twila Moon, a researcher at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC). NSIDC is part of the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) at the University of Colorado Boulder.

"We know that sea level will go up in the future," Moon said. "The challenge is to understand how quickly it will rise, and one element of that is better understanding how Greenland glaciers behave."

Moon and colleagues from the University of Washington focused on 16 glaciers in northwest Greenland, collecting detailed information on glacier speed, terminus position (the "end" of the glacier in the ocean) and sea ice conditions, during the years 2009-2014.

Sea ice had an important influence on the glaciers: When the waters in front of the glacier were completely covered by sea ice, the ends of the glaciers often advanced out away from land; icebergs that might otherwise have broken off and floated away stayed attached. When sea ice broke up in the spring, the ends of the glaciers usually quickly retreated back toward land as icebergs broke away.

By contrast, seasonal swings in glacier speed had little to do with sea ice conditions or glacier terminus location. Rather, the speed (velocity) of ice flow is likely responding to changes in the surface melt on top of the ice sheet and the movement of meltwater through and under the ice sheet.

Over the longer-term, however, Moon and her colleagues found a tight relationship between the speed of glaciers and terminus location. When sea ice levels were especially low and glaciers' toes (termini) retreated more than normal and then didn't re-advance, the glaciers sped up, moving ice toward the sea more quickly. While low sea ice is likely not the full cause of the changes, it may be a visible indication of other processes, such as subsurface ice melt, that also affect terminus retreat, Moon said.

It's important to recognize that the mechanisms driving seasonal glacier changes--in northwestern Greenland and around the world--are not necessarily the same ones driving longer-term trends, Moon said. Knowing the differences may help researchers better anticipate the impact of anomalously low sea ice years, for example.

"We do know we're going to see sea ice reduction in this area, and it's possible we can begin to estimate how that may affect glacier velocities," Moon said. It's also possible, she said, that researchers and communities interested in long-term glacial changes--the kind that affect sea levels--may not need to focus as much on seasonal advance and retreat of the rivers of ice.

"It may be that we need to instead pay more attention to these out-of-bounds events, these anomalous years of very low sea ice or very high melt that likely have the greatest influence on longer-term trends."

INFORMATION:

The American Geophysical Union is dedicated to advancing the Earth and space sciences for the benefit of humanity through its scholarly publications, conferences, and outreach programs. AGU is a not-for-profit, professional, scientific organization representing more than 60,000 members in 139 countries. Join the conversation on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and our other social media channels.

This press release and accompanying images can be found at: http://news.agu.org/press-release/the-ebb-and-flow-of-greenlands-glaciers/

AGU Contact:

Nanci Bompey

+1 (202) 777-7524

nbompey@agu.org

CIRES Contact:

Katy Human

+1 (303) 735-0196

Kathleen.human@colorado.edu

Washington, DC, June 1, 2015 - Tweets regarding the Ebola outbreak in West Africa last summer reached more than 60 million people in the three days prior to official outbreak announcements, according to a study published in the June issue of the American Journal of Infection Control, the official publication of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC).

Researchers from the Columbia University School of Nursing in New York analyzed over 42,000 Ebola-related tweets posted to the social networking site Twitter, from July 24 - August ...

In the last 40 years, fructose, a simple carbohydrate derived from fruit and vegetables, has been on the increase in American diets. Because of the addition of high-fructose corn syrup to many soft drinks and processed baked goods, fructose currently accounts for 10 percent of caloric intake for U.S. citizens. Male adolescents are the top fructose consumers, deriving between 15 to 23 percent of their calories from fructose--three to four times more than the maximum levels recommended by the American Heart Association.

A recent study at the Beckman Institute for Advanced ...

Biology isn't the only reason women eat less as they near ovulation, a time when they are at their peak fertility.

Three new independent studies found that another part of the equation is a woman's desire to maintain her body's attractiveness, says social psychologist and assistant professor Andrea L. Meltzer, Southern Methodist University, Dallas.

Women nearing ovulation who also reported an increase in their motivation to manage their body attractiveness reported eating fewer calories out of a desire to lose weight, said Meltzer, lead researcher on the study.

When ...

Bethesda, MD (June 1, 2015) -- The antiviral drug telbivudine prevents perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus (HBV), according to a study1 in the June issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association.

"If we are to decrease the global burden of hepatitis B, we need to start by addressing mother-to-infant transmission, which is the primary pathway of HBV infection," said study author Yuming Wang from Institute for Infectious Diseases, Southwest Hospital, Chongqing, China. "We ...

The following research will be presented at the American Physical Society's 2015 Division of Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics (DAMOP) meeting that will take place June 8-12, 2015 at the Hyatt Regency Columbus and the Greater Columbus Convention Center in Columbus, Ohio.

FINDING VENUS AND SEARCHING FOR EXOPLANETS

Thursday, June 11, 8:48 AM, Room: Franklin CD

Telescopes aren't the only way to detect the presence of Venus passing by. It's also now possible to measure the relative motion of the Earth and Sun so precisely that physicists can use the measurement to ...

Policy makers need to budget more than 288 million pounds over the next 40 years to adequately provide health care to all British soldiers who suffered amputations because of the Afghan war. This is the prediction of Major DS Edwards of the Royal Centre for Defence Medicine in the UK, in a new article appearing in the journal Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, published by Springer. He led a study into the scale and long-term economic cost of military amputees following Britain's involvement in Afghanistan between 2003 and 2014.

The authors describe the traumatic ...

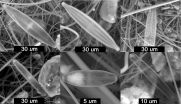

HOUSTON - (June 1, 2015) - The remains of tiny creatures found deep inside a mountaintop glacier in Peru are clues to the local landscape more than a millennium ago, according to a new study by Rice University, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and Ohio State University.

The unexpected discovery of diatoms, a type of algae, in ice cores pulled from the Quelccaya Summit Dome Glacier demonstrate that freshwater lakes or wetlands that currently exist at high elevations on or near the mountain were also there in earlier times. The abundant organisms would likely have been ...

Researchers from the University of Liverpool have found that approximately half of patients who have an eye removed because of a form of eye cancer experience `phantom eye syndrome.'

Patients with the condition experience "seeing" and pain in the eye that is no longer there. Researchers assessed 179 patients whose eye had been removed as a result of a cancer, called intraocular melanoma.

They found that more than a third of the patients experienced phantom eye symptoms every day. In most patients, the symptoms ceased spontaneously, but some patients reported that they ...

Understanding the volcanic activity on Earth is not only important in order to limit the impact of natural disasters, volcanic eruptions also have a large impact on the climate and evolution of life on our planet. However, many details in the history of volcanic activity are still unknown. Scientists from the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, together with colleagues from the USA, Taiwan, Australia and Switzerland, now have been able to track the development of the Galapagos volcanoes in the time frame between eight and 16 million years ago. In the process ...

Insulin degludec (trade name: Tresiba) has been approved since January 2015 for adolescents and children from the age of one year with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus. In an early benefit assessment pursuant to the Act on the Reform of the Market for Medicinal Products (AMNOG), the German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG) has now examined whether this new drug, alone or in combination with other blood-glucose lowering drugs, offers an added benefit over the appropriate comparator therapy.

No added benefit of insulin degludec for adolescents ...