(Press-News.org) CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- New compounds that specifically attack fungal infections without attacking human cells could transform treatment for such infections and point the way to targeted medicines that evade antibiotic resistance.

Led by University of Illinois chemistry professor Martin D. Burke, a team of chemists, microbiologists and immunologists developed and tested several derivatives of the antifungal drug amphotericin B (pronounced am-foe-TARE-uh-sin B). They published their findings in the journal Nature Chemical Biology.

Amphotericin B is doctors' last, best defense against life-threatening fungal infections that invade a patient's blood and tissues, said Burke, who also is a medical doctor and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Early Career Scientist. In half a century of use, amphotericin has yet to be overcome by new resistant strains of pathogens.

"The problem with this drug is that it is also highly toxic, particularly to the kidneys, and this limits the dose that can be given to a patient. As a result, invasive fungal infections still carry a mortality rate of about 50 percent, resulting in more than 1.5 million deaths each year - more than malaria or tuberculosis," said Burke.

Burke's group previously discovered that amphotericin B kills yeast and fungi by targeting a particular lipid molecule essential to the microbe's physiology, which is what makes it such an effective treatment, but it also binds to cholesterol in humans, which is thought to be what makes it so toxic.

In the new paper, Burke's group performed three simple chemical steps to convert amphotericin B to compounds that would bind more specifically to the lipid in fungi but not to cholesterol. They found particular derivatives that were extremely effective in killing invasive yeast infections in mice, but without the mice showing any signs of toxicity - even at much higher doses than a fatal dose of amphotericin B.

The researchers were concerned that because the drugs acted so specifically, resistant strains might emerge much faster. However, even when trying to generate mutations that would make yeast resistant, the researchers found that the derivatives were as elusive to resistance as the original amphotericin B, thus proving that targeted drugs and low resistance are not mutually exclusive.

"It has long been suspected that the unique capacity for amphotericin B to evade new resistance and its exceptional toxicity were inextricably linked," Burke said. "We were surprised and very gratified to find that these derivatives are no more vulnerable to resistance than amphotericin B, which has evaded new resistance development in patients for more than half a century."

"Learning more about basic chemical processes paves the way for medical advances," said Jon Lorsch, the director of the National Institutes of Health's National Institute of General Medical Sciences, which partially funded the research. "In this elegant example, detailed knowledge of how a drug interacts with its target has pointed not only to possible improvements in our ability to treat life-threatening fungal infections, but also to a new approach for designing antimicrobial drugs."

Since amphotericin B is manufactured in mass quantities, the new compounds also could be made on a large scale. REVOLUTION Medicines, a company Burke co-founded, has licensed the compounds to develop optimal drug candidates and to pursue clinical studies.

Burke hopes that this method of tweaking naturally occurring compounds to make them more specific and less toxic not only produces better therapies for life-threatening fungal infections, but also helps in the development of other medications that circumvent resistance.

"More broadly, these results suggest that binding microbial-specific lipids that are critical for microbial physiology could represent a more general path to nontoxic yet resistance-evasive antimicrobial agents," Burke said.

INFORMATION:

Editor's notes: To reach Martin "Marty" Burke, call 217-244-8726; email: burke@scs.illinois.edu. The paper, "Nontoxic antimicrobials that evade drug resistance," is available from Nature Press, press@nature.com.

WASHINGTON, DC, June 1, 2015 -- Non-heterosexual women who feel a disconnect between who they are attracted to and how they identify themselves may have a higher risk of alcohol abuse, according to a new study led by Amelia E. Talley, an assistant professor in Texas Tech University's Department of Psychological Sciences.

The study, titled "Longitudinal Associations among Discordant Sexual Orientation Dimensions and Hazardous Drinking in a Cohort of Sexual Minority Women," appears in the June issue of the Journal of Health and Social Behavior. It delves into the reasons ...

A new study links a commonly used household pesticide with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and young teens.

The study found an association between pyrethroid pesticide exposure and ADHD, particularly in terms of hyperactivity and impulsivity, rather than inattentiveness. The association was stronger in boys than in girls.

The study, led by researchers at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, is published online in the journal Environmental Health.

"Given the growing use of pyrethroid pesticides and the perception that they may ...

WASHINGTON, D.C. - In northwestern Greenland, glaciers flow from the main ice sheet to the ocean in see-sawing seasonal patterns. The ice generally flows faster in the summer than in winter, and the ends of glaciers, jutting out into the ocean, also advance and retreat with the seasons.

Now, a new analysis shows some important connections between these seasonal patterns, sea ice cover and longer-term trends. Glaciologists hope the findings, accepted for publication in the June issue of the American Geophysical Union's Journal of Geophysical Research-Earth Surface and ...

Washington, DC, June 1, 2015 - Tweets regarding the Ebola outbreak in West Africa last summer reached more than 60 million people in the three days prior to official outbreak announcements, according to a study published in the June issue of the American Journal of Infection Control, the official publication of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC).

Researchers from the Columbia University School of Nursing in New York analyzed over 42,000 Ebola-related tweets posted to the social networking site Twitter, from July 24 - August ...

In the last 40 years, fructose, a simple carbohydrate derived from fruit and vegetables, has been on the increase in American diets. Because of the addition of high-fructose corn syrup to many soft drinks and processed baked goods, fructose currently accounts for 10 percent of caloric intake for U.S. citizens. Male adolescents are the top fructose consumers, deriving between 15 to 23 percent of their calories from fructose--three to four times more than the maximum levels recommended by the American Heart Association.

A recent study at the Beckman Institute for Advanced ...

Biology isn't the only reason women eat less as they near ovulation, a time when they are at their peak fertility.

Three new independent studies found that another part of the equation is a woman's desire to maintain her body's attractiveness, says social psychologist and assistant professor Andrea L. Meltzer, Southern Methodist University, Dallas.

Women nearing ovulation who also reported an increase in their motivation to manage their body attractiveness reported eating fewer calories out of a desire to lose weight, said Meltzer, lead researcher on the study.

When ...

Bethesda, MD (June 1, 2015) -- The antiviral drug telbivudine prevents perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus (HBV), according to a study1 in the June issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association.

"If we are to decrease the global burden of hepatitis B, we need to start by addressing mother-to-infant transmission, which is the primary pathway of HBV infection," said study author Yuming Wang from Institute for Infectious Diseases, Southwest Hospital, Chongqing, China. "We ...

The following research will be presented at the American Physical Society's 2015 Division of Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics (DAMOP) meeting that will take place June 8-12, 2015 at the Hyatt Regency Columbus and the Greater Columbus Convention Center in Columbus, Ohio.

FINDING VENUS AND SEARCHING FOR EXOPLANETS

Thursday, June 11, 8:48 AM, Room: Franklin CD

Telescopes aren't the only way to detect the presence of Venus passing by. It's also now possible to measure the relative motion of the Earth and Sun so precisely that physicists can use the measurement to ...

Policy makers need to budget more than 288 million pounds over the next 40 years to adequately provide health care to all British soldiers who suffered amputations because of the Afghan war. This is the prediction of Major DS Edwards of the Royal Centre for Defence Medicine in the UK, in a new article appearing in the journal Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, published by Springer. He led a study into the scale and long-term economic cost of military amputees following Britain's involvement in Afghanistan between 2003 and 2014.

The authors describe the traumatic ...

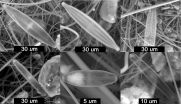

HOUSTON - (June 1, 2015) - The remains of tiny creatures found deep inside a mountaintop glacier in Peru are clues to the local landscape more than a millennium ago, according to a new study by Rice University, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and Ohio State University.

The unexpected discovery of diatoms, a type of algae, in ice cores pulled from the Quelccaya Summit Dome Glacier demonstrate that freshwater lakes or wetlands that currently exist at high elevations on or near the mountain were also there in earlier times. The abundant organisms would likely have been ...