(Press-News.org) University of Adelaide researchers have discovered cerebral palsy has an even stronger genetic cause than previously thought, leading them to call for an end to unnecessary caesareans and arbitrary litigation against obstetric staff.

In an authoritative review published in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, members of the Australian Cerebral Palsy Research Group, based at the University of Adelaide's Robinson Research Institute, argue that up to 45% of cerebral palsy cases can have genetic causes.

This builds on research published in February this year by the group which found at least 14% of cerebral palsy cases are likely to be caused by a genetic mutation. And the group expects the percentage of genetically caused cerebral palsy cases will continue to increase as genetic sequencing techniques evolve.

The University of Adelaide's Emeritus Professor Alastair MacLennan, leader of the research group, says the realisation by courts that many cases of cerebral palsy cannot be prevented by differences in labour management should reduce the adverse influence of obstetric litigation.

"For many years it was assumed, without good evidence, cerebral palsy was caused by brain damage at birth through lack of oxygen. This belief along with the temptation to blame the insured, and the high cost of caring for children with cerebral palsy, has fuelled litigation against obstetric staff," says Emeritus Professor MacLennan.

"Numerous recent studies have shown that despite an increase in caesarean deliveries over 50 years, which have risen from 5% to 34% in Australia, there has been no overall change in cerebral palsy rates.

"Some of the increase in caesareans appears to be due to defensive obstetrics and fear of litigation - there are lower rates of caesareans in countries with a "no-fault insurance scheme" like New Zealand, where rates are 23%.

"It's estimated that $300 million is paid on cerebral palsy settlements in Australia each year. I hope that our research will help end unfounded cerebral palsy related litigation," he says.

Several more years of research are needed but the research group believes that eventually cerebral palsy genetic testing before, during and after pregnancy will be introduced.

"It is now becoming apparent that cerebral palsy is an umbrella diagnosis for children with non-progressive disorders of movement control and posture, and that there are many types and antenatal influences including genetic causes," says the University of Adelaide's Professor Jozef Gecz, Head of Neurogenetic Research, Robinson Research Institute.

"Cerebral is akin to many other neurodevelopmental disorders such as intellectual disability, autism and epilepsy, co-morbidities that are often seen with cerebral palsy, and they too have many genetic causes," he says.

"Many children who have received a diagnosis of cerebral palsy may have an inherited or spontaneous genetic cause and this is exciting because we can now focus research on the beginning of pregnancy and not so unfruitfully on the circumstances of birth," says Dr Suzanna Thompson, co-author on the paper and paediatric neurologist at the Women's and Children's Hospital, Adelaide.

INFORMATION:

A study of marine mammals and other protected species finds that several once endangered species, including the iconic humpback whale, the northern elephant seal and green sea turtles, have recovered and are repopulating their former ranges.

The research, published in the June edition of Trends in Ecology and Evolution, suggests that some species, including humpback whales, have reached population levels that may warrant removal from endangered species lists.

But returning species, which defy global patterns of biodiversity loss, create an urgent new challenge for policymakers ...

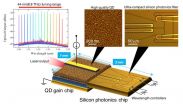

Researchers at Tohoku University and the National Institute of Information and Communications Technology (NICT) in Japan, have developed

a novel ultra-compact heterogeneous wavelength tunable laser diode. The heterogeneous laser diode was realized through a combination

of silicon photonics and quantum-dot (QD) technology, and demonstrates a wide-range tuning-operation.

The researchers presented their work at a Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics (CLEO) in San Jose, California, on May 13. The related

paper was also be published in Applied Physics Express ...

A research group at Tohoku University has succeeded in fabricating an atomically thin, high-temperature superconductor film with a superconducting transition temperature (Tc) of up to 60 K (-213°C). The team, led by Prof. Takashi Takahashi (WPI-AIMR) and Asst. Prof. Kosuke Nakayama (Dept. of Physics), also established the method to control/tune the Tc.

This finding not only provides an ideal platform for investigating the mechanism of superconductivity in the two-dimensional system, but also paves the way for the development of next-generation nano-scale superconducting ...

An international team led by Thayne Currie of the Subaru Telescope and using the Gemini South telescope, has discovered a young planetary system that shares remarkable similarities to our own early solar system. Their images reveal a ring-like disk of debris surrounding a Sun-like star, in a birth environment similar to the Sun's. The disk appears to be sculpted by at least one unseen solar system-like planet, is roughly the same size as our solar system's Edgeworth-Kuiper Belt (commonly called the Kuiper Belt), and may contain dust and icy particles. This work provides ...

Using a brand new survey method, researchers in Bergen have asked a broad spectrum of people in Norway about their thoughts on climate change. The answers are quite surprising.

Some 2,000 Norwegians have been asked about what they think when they hear or read the words "climate change". There were no pre-set answers or "choose the statement that best describes your view" options. Instead the respondents had to formulate their views on climate change in their own words. The answers have provided striking new insight into what the average person on the street in Norway ...

Long-term changes in immune function caused by childhood trauma could explain increased vulnerability to a range of health problems in later life, according to new research by the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience (IoPPN) at King's College London and the NIHR Maudsley BRC.

The study, published today in Molecular Psychiatry, found heightened inflammation across three blood biomarkers in adults who had been victims of childhood trauma. High levels of inflammation can lead to serious and potentially life-threatening conditions such as type-2 diabetes, cardiovascular ...

Treatment options for chronic hepatitis C, a serious and life-threatening infection, have improved substantially and several new regimens with shorter durations and improved efficacy and safety profiles are now available.

Groups have raised concerns about the evidence used to support the approval of some newer drugs, however, and the issue has been used to cast doubt on their efficacy and even to question treatment or deny reimbursement.

To address these concerns, the US Food and Drug Administration's Division of Antiviral Products in the Center for Drug Evaluation ...

This news release is available in French. Montreal, June 2 -- A new study published by the team of Naguib Mechawar, Ph.D., a researcher with the McGill Group for Suicide Studies (MGSS) of the Douglas Institute (CIUSSS de l'Ouest-de-l'Ile de Montreal) and associate professor in the Department of Psychiatry at McGill University, sheds new light on the disruption of astrocytes in depression. Astrocytes, a class of non-neuronal cells, have previously been implicated in depression and suicide.

However, it was not known whether these cells were affected throughout the brain ...

Los Angeles, CA (June 2, 2015) Neighborhoods with more interpersonal conflict, such as domestic violence and landlord/tenet disputes, see more serious crime according to a new study out today in Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency (JRCD). Private conflict was a better predictor of neighborhood deterioration than public disorder, such as vandalism, suggesting the important role that individuals play in community safety.

"Private conflicts, for example, domestic violence or friendship disputes over money or girlfriends, can and do spill over into public spaces, ...

Scientists from the University of Louvain have discovered that a key element of infant brain development occurs years earlier than previously thought.

The way we perceive faces -- using the right hemisphere of the brain -- is unique and sets us apart from non-human primates. It was thought that this ability develops as we learn to read, but a new study published in the journal eLife shows that in babies as young as four months it is already highly evolved.

"Just as language is impaired following damage to the brain's left hemisphere, damage to the right hemisphere ...