(Press-News.org) Evolutionary theorist Stephen Jay Gould is famous for describing the evolution of humans and other conscious beings as a chance accident of history. If we could go back millions of years and "run the tape of life again," he mused, evolution would follow a different path.

A study by University of Pennsylvania biologists now provides evidence Gould was correct, at the molecular level: Evolution is both unpredictable and irreversible. Using simulations of an evolving protein, they show that the genetic mutations that are accepted by evolution are typically dependent on mutations that came before, and the mutations that are accepted become increasingly difficult to reverse as time goes on.

The research team consisted of postdoctoral researchers and co-lead authors Premal Shah and David M. McCandlish and professor Joshua B. Plotkin, all from Penn's Department of Biology in the School of Arts & Sciences. They reported their findings in this week's Early Edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The study focuses exclusively on the type of evolution known as purifying selection, which favors mutations that have no or only a small effect in a fixed environment. This is in contrast to adaptation, in which mutations are selected if they increase an organism's fitness in a new environment. Purifying selection is by far the more common type of selection.

"It's the simplest, most boring type of evolution you can imagine," Plotkin said. "Purifying selection is just asking an organism to do what it's doing and keep doing it well."

As an evolutionary model, the Penn team used the bacterial protein argT, for which the three-dimensional structure is known. Its small size means that the researchers could reliably predict how a given genetic mutation would affect the protein's stability.

Using a computational model, they simulated the protein evolving during the equivalent of roughly 10 million years by randomly introducing mutations, accepting them if they did not significantly affect the protein's stability and rejecting them if they did. They then examined pairs of mutations, asking whether the later mutation would have been accepted had the earlier mutation not have been made.

"The very same mutations that were accepted by evolution when they were proposed, had they been proposed at a much earlier in time, they would have been deleterious and would have been rejected," Plotkin said.

This result -- that later mutations were dependent on the earlier ones -- demonstrates a feature known as contingency. In other words, mutations that are accepted by evolution are contingent upon previous mutations to ameliorate their effects.

The researchers then asked a distinct, converse question: whether it is possible to revert an earlier mutation and still maintain the protein's stability. They found that the answer was no. Mutations became "entrenched" and increasingly difficult to revert as time went on without having a destabilizing effect on the protein.

"At each point in time, if you make a substitution, you wouldn't see a large change in stabilization," Shah said. "But, after a certain number of changes to the protein, if you go back and try to revert the earlier change, the protein structure begins to collapse."

The concepts of contingency and entrenchment were well known to be present in adaptive evolution, but it came as a surprise to the researchers to find them under purifying selection.

"We thought we would just try this with purifying selection and see what happened and were surprised to see how much contingency and entrenchment occurs," Plotkin said. "What this tells us is that, in a deep sense, evolution is unpredictable and in some sense irreversible because of interactions between mutations."

Such interactions, when the effect of a mutation is dependent on another, are known as epistasis. The researchers' investigation found that, unexpectedly, purifying selection enriches for epistatic mutations as opposed to mutations that are simply additive. Plotkin explained that this is because purifying selection favors mutations that have a small effect. Either the mutation can have a small effect on its own, or it can have a small effect because another, earlier mutation ameliorated the effects of the current mutation. Thus mutations that are dependent upon earlier mutations will be favored.

"Our study shows, and this has been known for a long time, that most of the substitutions that occur are substitutions that have small effects," McCandlish said. "But what's interesting is that we find that the substitutions that have small effects change over time."

An implication of these findings is that predicting the course of evolution, as one might wish to do, say, to make an educated guess as to what flu strain might arise in a given year, is not easy.

"The way these substitutions occur, since they're highly contingent on what happened before, makes predictions of long-term evolution extremely difficult," Plotkin said.

The researchers hope to partner with other groups in the future to conduct laboratory experiments with microbes to confirm that real-world evolution supports their findings.

And while Gould's comment about replaying the tape of life was mainly a nod to the large amount of randomness inherent in evolution's path, this study suggests a more nuanced reason that the playback would appear different.

"There is intrinsically a huge amount of contingency in evolution," Plotkin said. "Whatever mutations happen to come first set the stage for what other later mutations are permissible. Indeed, history channels evolution down a certain path. Gould's famous tape of life would be very different if replayed, even more different than Gould might have imagined."

INFORMATION:

The study was supported by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the U.S. Department of the Interior, Foundational Questions in Evolutionary Biology, the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Army Research Office and the National Science Foundation.

Planets with volcanic activity are considered better candidates for life than worlds without such heated internal goings-on.

Now, graduate students at the University of Washington have found a way to detect volcanic activity in the atmospheres of exoplanets, or those outside our solar system, when they transit, or pass in front of their host stars.

Their findings, published in the June issue of the journal Astrobiology, could aid the process of choosing worlds to study for possible life, and even one day help determine not only that a world is habitable, but in fact ...

Researchers in UC Santa Barbara professor Yasamin Mostofi's lab are proving that wireless signals can do more than provide Internet access. They have demonstrated that a WiFi signal can be used to count the number of people in a given space, leading to diverse applications, from energy efficiency to search-and-rescue.

'Our approach can estimate the number of people walking in an area, based on only the received power measurements of a WiFi link,' said Mostofi, a professor of electrical and computer engineering. This approach does not require people to carry WiFi-enabled ...

DARIEN, Ill. -- A new study suggests that poor sleep quality is associated with reduced resilience among veterans and returning military personnel.

Results show that 63 percent of participants endorsed poor sleep quality, which was negatively associated with resilience. Longer sleep onset, lower sleep efficiency, shorter sleep duration, worse sleep quality, and greater daytime disturbance were each associated with lower resilience. Findings suggest that appraisal of sleep quality may contribute to resilience scores more than self-reported sleep efficiency.

'To our knowledge, ...

In 2009, scientists from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution embarked on a NASA-funded mission to the Mid-Cayman Rise in the Caribbean, in search of a type of deep-sea hot-spring or hydrothermal vent that they believed held clues to the search for life on other planets. They were looking for a site with a venting process that produces a lot of hydrogen because of the potential it holds for the chemical, or abiotic, creation of organic molecules like methane - possible precursors to the prebiotic compounds from which life on Earth emerged.

For more than a decade, the ...

BOSTON -- Diabetes patients with abnormal blood sugar levels had longer, more costly hospital stays than those with glucose levels in a healthy range, according to studies presented by Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute researchers at the 75th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association (ADA), which ends June 9 in Boston.

The findings come as more patients are being admitted into U.S. hospitals with diabetes as an underlying condition. A recent UCLA public health report indicated that one of every three hospital patients admitted in California has a diagnosis ...

BOSTON (June 8, 2015) -- One member of a widely prescribed class of drugs used to lower blood glucose levels in people with diabetes has a neutral effect on heart failure and other cardiovascular problems, according to the first clinical trial to examine cardiovascular safety in a GLP-1 receptor agonist, presented at the American Diabetes Association's 75th Scientific Sessions.

The Evaluation of Lixisenatide in Acute Coronary Syndrome (ELIXA) study also found a modest benefit for weight control, and no increase of risk for hypoglycemia or pancreatic injury in those who ...

A team of researchers from UC San Diego, Florida State University and Pacific Northwest National Laboratories has for the first time visualized the growth of 'nanoscale' chemical complexes in real time, demonstrating that processes in liquids at the scale of one-billionth of a meter can be documented as they happen.

The achievement, which will make possible many future advances in nanotechnology, is detailed in a paper published online today in the Journal of the American Chemical Society. Chemists and material scientists will be able to use this new development in their ...

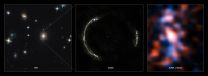

ALMA's Long Baseline Campaign has produced a spectacularly detailed image of a distant galaxy being gravitationally lensed. The image shows a magnified view of the galaxy's star-forming regions, the likes of which have never been seen before at this level of detail in a galaxy so remote. The new observations are far more detailed than those made using the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, and reveal star-forming clumps in the galaxy equivalent to giant versions of the Orion Nebula.

ALMA's Long Baseline Campaign has produced some amazing observations, and gathered unprecedentedly ...

An international, multidisciplinary team including investigators from Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) has found that lixisenatide, a member of a class of glucose-lowering drugs frequently prescribed in Europe to patients with diabetes, did not increase risk of cardiovascular events including heart failure. These results - the first to be reported on the cardiovascular safety of a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist - were presented today at the American Diabetes Association's 75th Scientific Sessions.

"There are a large number of patients around the world ...

ORANGE, Calif. -- In a study just published by researchers at Chapman University, findings showed that greater life satisfaction in adults older than 50 years of age is related to a reduced risk of mortality. The researchers also found that variability in life satisfaction across time increases risk of mortality, but only among less satisfied people. The study involved nearly 4,500 participants who were followed for up to nine years.

'Although life satisfaction is typically considered relatively consistent across time, it may change in response to life circumstances ...