(Press-News.org) In 2009, scientists from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution embarked on a NASA-funded mission to the Mid-Cayman Rise in the Caribbean, in search of a type of deep-sea hot-spring or hydrothermal vent that they believed held clues to the search for life on other planets. They were looking for a site with a venting process that produces a lot of hydrogen because of the potential it holds for the chemical, or abiotic, creation of organic molecules like methane - possible precursors to the prebiotic compounds from which life on Earth emerged.

For more than a decade, the scientific community has postulated that in such an environment, methane and other organic compounds could be spontaneously produced by chemical reactions between hydrogen from the vent fluid and carbon dioxide (CO2). The theory made perfect sense, but showing that it happened in nature was challenging.

Now we know why: an analysis of the vent fluid chemistry proves that for some organic compounds, it doesn't happen that way.

New research by geochemists at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, published June 8 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, is the first to show that methane formation does not occur during the relatively quick fluid circulation process, despite extraordinarily high hydrogen contents in the waters. While the methane in the Von Damm vent system they studied was produced through chemical reactions (abiotically), it was produced on geologic time scales deep beneath the seafloor and independent of the venting process. Their research further reveals that another organic abiotic compound is formed during the vent circulation process at adjacent lower temperature, higher pH vents, but reaction rates are too slow to completely reduce the carbon all the way to methane.

"We've really improved our understanding of the origin of abiotic hydrocarbons in all ridge-crest hydrothermal systems by identifying specifically where carbon is being transformed within the vent fluid circulation pathway," said Jill McDermott, lead author of the study and a recent graduate of the MIT/WHOI Joint Program in Oceanography. "We also have a much better sense of how quickly these reactions are occurring in natural systems - some take thousands of years, while others only take hours to days."

Methane and other organic compounds in natural waters can originate from three types of sources: living organisms, decomposition of living or dead biomass, and 'abiotic' formation via purely chemical processes with no participation from living organisms.

Finding out how methane and other organic species are formed in deep-sea hydrothermal systems is compelling because these compounds support modern day life, providing energy for microbial communities in the deep biosphere, and because of the potential role of abiotically-formed organic compounds in the origin of life.

The study, whose authors also include WHOI geochemists Jeffrey Seewald, Christopher German, and Sean Sylva, indicates that methane at the Von Damm vent field was created by a reaction between CO2 and water trapped for thousands of years within cooling volcanic rocks deep within Earth's crust. Many vent sites are tectonically active, and when tectonic shifts occur, the rocks beneath the sea floor can crack, allowing seawater to penetrate and leach methane from within the rocks. Eventually that methane is carried up to the seafloor by the circulating vent water. While this concept had previously been theorized, this paper is the first to demonstrate its importance in nature.

How the researchers determined this was a neat trick, involving balancing the vent site's CO2 budget by measuring the amount of CO2 in seawater in the vent fluid; analyzing the isotopic makeup of the CO2; and radiocarbon dating the CO2. The results of the analysis showed there has been no CO2 added, and no CO2 removed, and therefore it could not have been used to form methane.

An examination of the methane showed it was "radiocarbon dead." That meant it was older than 50,000 years and carried no modern signature, indicating the methane came from ancient geologic sources.

"We were able to use enough different but complementary lines of evidence to show that the methane formation here is a purely chemical process, and that it happens in the absence of life," said McDermott.

But why wasn't the CO2 at this site reacting with the hydrogen to create methane? That question led to an equally fascinating discovery: a reaction between CO2 and hydrogen was occurring, but it wasn't proceeding fast enough or progressing far enough to create methane.

Instead CO2 and hydrogen combined to create an "intermediate" compound called formate - an important "pre-biotic" organic compound.

The team discovered the formate when analyzing the vent fluids at cooler off-shoot vent sites at the Von Damm site and found it had less CO2 than it should have. That meant the CO2 must have been reacting to form something else. They determined the formate concentration in those fluids, and, said McDermott, "it turns out the amount of formate species that was formed in each one of these fluids, perfectly matches the amount of CO2 that was lost. It's so rare that you can actually close the budget, and figure out where all the carbon has gone." The amount of formate present also matched the amount predicted by thermodynamic models.

"This is an excellent example where hypotheses developed over the years from laboratory experiments and theoretical models could be tested and verified in nature," said co-author Seewald.

Intermediate species like formate have a lot of energy available. They're also a good energy source for microbes.

In fact, formate may be used by modern day microbes to generate methane in the subsurface biosphere. Formate may also have served as the first step toward forming reduced carbon compounds that were central to primitive biochemical pathways on early Earth.

"A particularly exciting aspect of this study is that our newest discoveries here on Earth provide a compelling 'real-world' example of just how pre-biotic chemistry could also arise elsewhere," said co-author German.

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by grants from NASA and the National Science Foundation. Additional funds were provided by the the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Ocean Ridge Initiative.

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution is a private, non-profit organization on Cape Cod, Mass., dedicated to marine research, engineering, and higher education. Established in 1930 on a recommendation from the National Academy of Sciences, its primary mission is to understand the ocean and its interaction with the Earth as a whole, and to communicate a basic understanding of the ocean's role in the changing global environment. For more information, please visit http://www.whoi.edu.

BOSTON -- Diabetes patients with abnormal blood sugar levels had longer, more costly hospital stays than those with glucose levels in a healthy range, according to studies presented by Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute researchers at the 75th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association (ADA), which ends June 9 in Boston.

The findings come as more patients are being admitted into U.S. hospitals with diabetes as an underlying condition. A recent UCLA public health report indicated that one of every three hospital patients admitted in California has a diagnosis ...

BOSTON (June 8, 2015) -- One member of a widely prescribed class of drugs used to lower blood glucose levels in people with diabetes has a neutral effect on heart failure and other cardiovascular problems, according to the first clinical trial to examine cardiovascular safety in a GLP-1 receptor agonist, presented at the American Diabetes Association's 75th Scientific Sessions.

The Evaluation of Lixisenatide in Acute Coronary Syndrome (ELIXA) study also found a modest benefit for weight control, and no increase of risk for hypoglycemia or pancreatic injury in those who ...

A team of researchers from UC San Diego, Florida State University and Pacific Northwest National Laboratories has for the first time visualized the growth of 'nanoscale' chemical complexes in real time, demonstrating that processes in liquids at the scale of one-billionth of a meter can be documented as they happen.

The achievement, which will make possible many future advances in nanotechnology, is detailed in a paper published online today in the Journal of the American Chemical Society. Chemists and material scientists will be able to use this new development in their ...

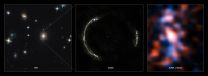

ALMA's Long Baseline Campaign has produced a spectacularly detailed image of a distant galaxy being gravitationally lensed. The image shows a magnified view of the galaxy's star-forming regions, the likes of which have never been seen before at this level of detail in a galaxy so remote. The new observations are far more detailed than those made using the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, and reveal star-forming clumps in the galaxy equivalent to giant versions of the Orion Nebula.

ALMA's Long Baseline Campaign has produced some amazing observations, and gathered unprecedentedly ...

An international, multidisciplinary team including investigators from Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) has found that lixisenatide, a member of a class of glucose-lowering drugs frequently prescribed in Europe to patients with diabetes, did not increase risk of cardiovascular events including heart failure. These results - the first to be reported on the cardiovascular safety of a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist - were presented today at the American Diabetes Association's 75th Scientific Sessions.

"There are a large number of patients around the world ...

ORANGE, Calif. -- In a study just published by researchers at Chapman University, findings showed that greater life satisfaction in adults older than 50 years of age is related to a reduced risk of mortality. The researchers also found that variability in life satisfaction across time increases risk of mortality, but only among less satisfied people. The study involved nearly 4,500 participants who were followed for up to nine years.

'Although life satisfaction is typically considered relatively consistent across time, it may change in response to life circumstances ...

Glenview, Ill. (June 8, 2015)-- A Canadian study published in the June issue of the journal CHEST found weight loss reduced asthma severity as measured by airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) in obese adults. The incidence of asthma is 1.47 times higher in obese people than nonobese people, and a three-unit increase in body mass index is associated with a 35% increase in the risk of asthma. The study supports the active treatment of comorbid obesity in individuals with asthma.

The study, the first of its kind to rely on appropriate physiologic tests as diagnostic criteria ...

Baltimore, Md. (Embargoed until 12:30 p.m. EDT, June 8, 2015) - Imaging lung cancer requires both precision and innovation. With this aim, researchers have developed a technique for clinical positron emission tomography (PET) imaging that creates advanced whole-body parametric maps, which allow quantitative evaluation of tumors and metastases throughout the body, according to research announced at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI).

Scientists have developed a novel agent for cancer imaging that seeks and attaches ...

Baltimore, Md. (Embargoed until 12:30 p.m. EDT, June 8, 2015) - A first-in-human study revealed at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI) shows how a powerful new drug finds and attaches itself to the ovarian and prostate cancer cells for both imaging and personalized cancer treatment.

The targeted aspect of the imaging agent, called I-124 PEG-AVP0458, is a small protein (avibody) linked to polyethylene glycol (PEG) chains. The drug compound is then labeled with the radionuclide iodine-124. Drugs like PEG-AVP0458 are ...

Baltimore, Md. (Embargoed until 12:30 p.m. EDT, June 8, 2015) - Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), a potentially devastating cancer of the blood and immune system, can range from relatively easy to treat to very aggressive. For more aggressive cases, post-treatment surveillance with molecular imaging could mean the early start of a new, life-saving treatment, say researchers presenting during the 2015 Annual Meeting of the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI).

NHL is the fifth most prevalent cancer in America, according to lead author Mehdi Taghipour, MD, ...